In 1971, the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka officially inaugurated the national office of the International Catholic Organisation for Cinema and Audio-visual (OCIC), under the guidance of the then Archbishop of Colombo, Dr Thomas Benjamin Cooray. The decision was based on reforms within the church aimed at increasing the role of the media, particularly after the Second Vatican Council of 1965, at which a papal decree, Inter mirifica, instructed authorities to make use of all forms of social communication, including the cinema.

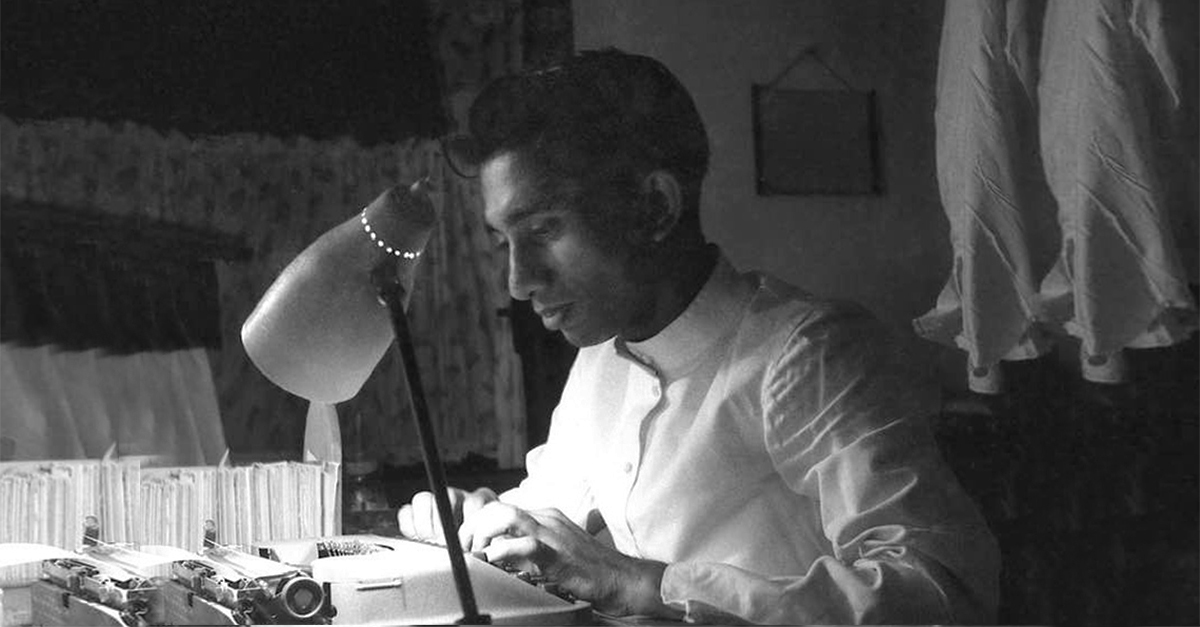

Father Ernest Poruthota, who passed away on June 22 at the age of 88, served as the first director of the OCIC’s Sri Lanka chapter, a position he occupied from 1972 to 1982. In that role, he made a most enduring contribution to the performing arts in the country, a contribution eloquently summed up by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in his condolence message, when he paid tribute to the Father’s “love for the Sinhala language, literature, and our unique identity.”

Early Years

Born Raymond Ernest Alexander Fernando in Puttalam in 1931, Father Poruthoto’s father, Jokinu Fernando, had worked as a lecturer at the Government Teachers’ College in Maggona, from where, due to some disagreements with authorities, he had been expelled, and as a punishment transferred to Marawila. Strong, willful, and stubborn, his father, as Poruthota remembered, “never even once tried to appeal the transfer.” Instead, he found solace printing literary and scientific books—including one very popular title from that period, Kaayika Vidyawa.

“I must have inherited the man’s stubbornness, which could explain why I rebelled against going to school,” Father Poruthota told me during a conversation we had some four years ago at St Peter and Paul’s Church in Lunawa, Moratuwa. The headstrong parent would drag the headstrong son almost every day to St Xavier’s College, where he obtained his primary education. “Eventually my parents realised I wouldn’t make it past secondary school. So they tried the Church,” he said. “In 1942, they admitted me to St Aloysius Seminary in Borella.”

At The Seminary

It was during these years that the young priest had his first brush with cinema, through the then Rector of the Seminary, who was friends with Albert Page, Chairman and Managing Director of Ceylon Theatres. “Page made it a habit to view English movies at the now-defunct Empire Theatre in Colombo before they were released,” Father Poruthota told me. “He sent some of them to the Seminary, where films were in general banned—not surprisingly, we only got to see Christian parables, like ‘The Song of Bernadette’.”

In 1957, Archbishop Cooray ordained Father Poruthota at St Lucia’s Cathedral in Kotahena. At the time, the prevalent attitude of the Church to the cinema was at best strained: the editorial of the Catholic Messenger of February 1959, for instance, went so far as to praise the Public Performance Board for banning Roger Vadim’s controversial “And God Created Woman”. “We congratulate the members of the Board today,” held the editorial, “for the high principles formulated by them according to which films must be judged.”

Those high principles would change considerably after the Second Vatican Council, when the Church came to realise that standards beyond religious morals could be used to judge a work of art. “By the time we opened the OCIC chapter here,” Poruthota said, “we were assessing films on how well they elevated their audiences.” This later became the main criterion used by the OCIC.

Life With Theatre And Cinema

Father Poruthota’s association with the theatre predates his involvement in the cinema. According to Sarath Amunugama, then a critic, journalist, and academic who was in touch with many of the country’s leading artists from that era, so keen was his love for the arts, he allowed the award-winning playwright Sugathapala de Silva’s group Ape Kattiya to practice in his parish premises, through his association with one of its key ideologues and co-founders, the critic Cyril B. Perera. Even this decision courted controversy: Ape Kattiya became known for its adaptations of modern American plays that revolved around otherwise taboo themes, like premarital sex and homosexuality. Through his connection to Perera, he befriended two other people who were to become lifelong acquaintances —the Ranasinghe brothers, Tony, a renowned stage and film actor, and Ralex, a renowned photographer and artist.

“The cultural revolution I witnessed,” he recalled, “shaped my belief in the freedom of the artist. The Church may not have accorded with me, but eventually, after the mid-1960s, it did.” The contacts he made then would prove crucial to the birth of the OCIC Awards. From 1977, when it held its first all-category ceremony (the OCIC had earlier christened it a “salutation ceremony”), he not only filled a vacuum in the industry—the biggest such event, the Sarasaviya Awards, having been discontinued after 1970 for administrative reasons that wouldn’t be resolved until 1980—but also took in, for the very first time, journalists as jury members. “Most juries had civil servants. We had writers,” Father Poruthota explained. Among these were Cyril B. Perera, Ralex Ranasinghe, and the eminent film critic and film activist Ashley Ratnabivushana. By the end of his tenure in 1982, they would guide the ceremony to its present-day format.

Other Contributions

What were his other contributions? Renowned film director Prasanna Vithanage, in a conversation with me, argued that there were six. Firstly, “he brought down films from Goethe-Institut, Alliance Française, the British Council, and the American Centre to a small place in Malwatta Road at Fort called Martin Piyathumage Tikiri Cinema Hala (‘Father Martin’s Mini Film Hall’),” he said. “We saw them on Fridays and Mondays.”

Secondly, Vithanage said, he would organise “discussions on new Sinhala films on Poya days,” where directors like H. D. Premaratne and Ananda Hewage would talk about their work, “moderated by the late Sunil Mihindukula.”

Thirdly, he talked of the impact of a three-day seminar conducted by Father Pouthota “for budding students” at Aquinas College, “where we got to see three films, including H. D. Premaratne’s ‘Apeksha’ and Dharmasena Pathiraja’s ‘Para Dige’, and were taught about feature films and documentaries.”

Then there were the publications, “at a time when not even the National Film Corporation undertook such an endeavour,” Vithanage said, adding that the OCIC, under Father Poruthota, had issued magazines and periodicals.

More significantly, Vithanage said, “he inaugurated a practical course, informally called the ‘Super 8mm Workshop’, headed by the late Andrew Jayamanne, from which a young and energetic generation of directors, including me and Christy Shelton Fernando, would graduate.”

All these, laudable as they are, pale before what Vithanage considers Father Poruthota’s greatest contribution to local cinema: “his opposition to censorship.” Poruthota himself told me this: “I’m against censorship of any sort,” he said. “By the government or by the Church.” A good example of this was when the then administration imposed a ban on Vithanage’s third film, ‘Purahanda Kaluwara’. Among those who stood by him, and against the directive, was Poruthota.

Veteran film critic Ajith Galappaththi agreed. “Father Poruthota did not always fall in line with what you had to say,” he told me. “He would always encourage you to debate a film with him, to discuss its aesthetic as well as its moral merits. And he ensured that you profited from such debates; that you, or he, understood something about a movie we hadn’t seen before,” he told me.

Galappaththi felt that what endeared people to Father Poruthota was his refusal to view human beings as groups or cliques. “As critics, we are often guilty of organising ourselves into factions,” he said. “Father Poruthota believed that if art was to flourish, we had to get together. There could be nothing exclusively Sinhala, Tamil, or Muslim about it.”

Perhaps what Vithanage said about him to me becomes most pertinent here: that by keeping the window open for newcomers to enter the industry, he kept the industry going, despite the many obstacles it continues to face.