When you finally give the Von Bloss family the slip, after 210 pages, you have developed new eyes and new responses to life – at the very least, you’ve acquired the leer and the snicker of the juvenile delinquent. Everything in your field of vision transforms, consolingly, into analogues of genitalia. The Von Bloss sensibility is a more latent development, and remains a sentimental undertow even after the catechism of Political Correctness reasserts itself. You admire the simplicity of Dunnyboy’s demands as he goes at everything “big-buttocked and round-thighed”; like Maudiegirl, you see the necessity of slow-braising half a zoo in a gallon of brandy for a wedding meal; you wish you could meet your problems halfway like Sonnaboy and “pound [them] to a pulp-like consistency”; and you long to pass like Cecilprins, “who had taken all that life threw at him and tossed it back.”

It is now an axiom of a university education that Carl Muller’s The Jam Fruit Tree was an irrevocable point in the evolution of the Sri Lankan novel. It is not. It is not even a novel. Although formally divided into four parts – the flowering, the berrying, bearing fruit, and the ripening – the story has little sense of direction, or destination. There are three structural pegs for the plot, a death, a deflowering, and another death; but the only progress the book makes is lateral – it sags with digressions. This is not a condemnation. This is a riddance of all the academic keywords that have entombed Muller. Now we can address the flesh, the helpless secretions and the compulsive abuses, of Muller’s art.

Life in Boteju Lane

The “fat and fifty” Maudiegirl is the vast substructure of the Von Bloss house in Boteju Lane, who sustains the jollity of the first part by concocting superabundant Burgher feasts and poultices and “miracles of healing”. Secretly postponing her death with her own home-cooked ointments, Maudiegirl is determined to see at least one of her girls married. She chooses the most conventional relationship among the complex knots into which her children have disappeared, and yokes her daughter Anna with a Sinhala-Buddhist man called Colontota (a supernumerary joke: the name means Colombo Port). The wedding, an amorphous brawl that confuses everyone – including the reader and writer – sprawls for 14 pages. At last, her ambitions spent and her Burgher blood proven, Maudiegirl crumbles. Her funeral is a brief, stealthy recalibration of stage and lighting: until we sober up we don’t realise how effortlessly Muller has been making us drunk with his humour. Without Maudiegirl to uphold the Boteju Lane house, the Von Blosses disintegrate into their individual quirks. Viva has a fit of Pentecostalism, breaks from the family, and convulses his whole life with biblical imprecations; Anna is claimed by the Sinhala-Buddhist trap of disapproval and self-denial; Totoboy staggers and spirals away towards cirrhosis; Leah discovers the arduous life of femdom and masturbation by proxy; Sonnaboy pursues the theoretical limits of violence and alcohol tolerance.

“And so she died and the shrieks and wailings and the broken sobs of the men were terrible to hear. And only Sonnaboy, dry-eyed but with an ache in his heart that could not be eased, said, ‘Viva never came…Papa, Viva never came…He killed our mama and he never came.’”

Along with Cecilprins, the bereaved patriarch, we look at Sonnaboy with “unseeing eyes”, waiting for the absurd reversions of comedy to raise Maudiegirl, and we keep waiting.

The second part of the book is a dense clutter of digressions, back-stories, flashbacks, pranks, and incestuous permutations, which Sonnaboy and Beryl, his sixteen-year old sweetheart, have to wade before they can have sex. It ends with a gratuitous ode to sensuality, a mix of Gregorian hymn and third-rate erotica, with the “birds in Heaven… in full throated song” and “the excruciating tickle of his pubic hair on her clitoris”, as Sonnaboy deflowers his bride. The third part gestates Sonnaboy’s and Beryl’s first child, Carloboy (a character of increasing importance in the sequels of Muller’s trilogy). However, those pages still feel crowded, with a single joke – an earlier breach of promise of marriage by Sonnaboy – that goes on, in Muller fashion, to proliferate its participants, to recombinate its cross-purposes, and then to repeat its punchlines.

The Lure of Nostalgia

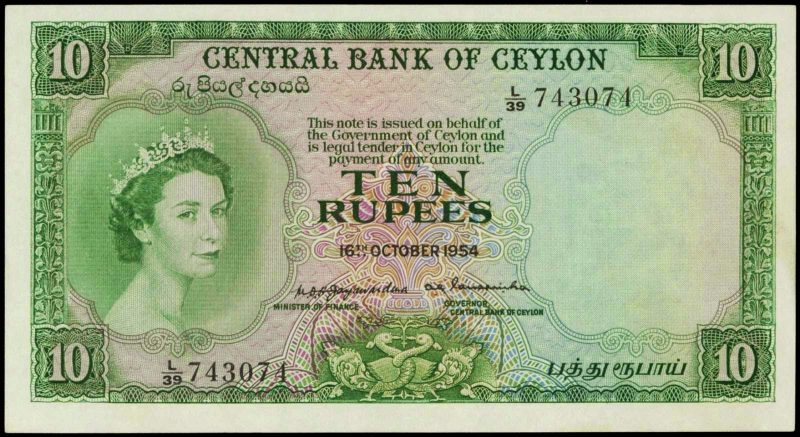

A ten rupee note that was used during British colonial rule. Image credit: worldbanknotescoins.com

By part four, Muller breaks his flow and, with a dutiful clearing of his throat, introduces us to a repulsive character we had no desire to meet: Sri Lankan history.

“The island, too, saw its traumas. After the war came the independence and the need to give the native Sinhalese a place in the sun… Burghers were told, learn Sinhalese, or else. The age of the favoured English-educated was over… Burghers in their thousands left the island.”

It occurs to us that The Jam Fruit Tree is not an interminable doggerel originating in some dim Irish pub, but a minimally rearranged family tree sprung from Sri Lankan soil. As Muller claims, “‘fact’ became ‘faction’… this is a work of ‘fictional-fact’ or factual-fiction’”. Even where the fiction fails, this book will be sold for its facts. Those Maudiegirl recipes continue for pages and pages after their structural purpose has been served, and, perhaps, feed the nostalgia of a generation forever reliving the post-colonial holiday.

The book ends with a Burgher Christmas – not a Burgher wedding, which is an homage to gluttony, but a Burgher Christmas, which is an homage to sloth. Patiently going through “ghee-rice and turkey, salt beef, gammon, roast beef, boiled tongue, stuffed tomatoes, curried pork…” the Von Blosses then partake in the laboriously devised mass sedative known as rich cake. Much later, through the haze of contentment, they notice that their father, Cecilprins, had died in his seat at some point of the day. As the last laugh subsides into a reverie and the hangover sets in, a few wistful sentences document the dissipation of the Burghers, to Australia, England, New Zealand, Canada…

Muller In The Universities

The Jam Fruit Tree is more often cited than read. This writer has met fewer people who can map the Von Bloss incest than people who argue that Carl Muller set a precedent for something called Sri Lankan English. Muller himself classifies his subspecies as those who “thought Dutch and spoke English which did nothing to phraseology or syntax”. What’s more, Muller documents another kind of “Burghers who had clawed their way up from the roistering, boisterous bottom rung to study hard, tread the rainbow of academic achievement and look back on their beginnings with pure horror.” The “common herd”, like Beryl’s mother Florrie, listens to their Cambridge locution and conclude that they “talked funny but that’s what comes of learning too much.” What Muller did was to set a precedent in craftsmanship: Sri Lankan novelists before Muller had no ear for dialogue. Suddenly, the average Burgher aunty was on the page with all her mixed metaphors and confused tenses. Here’s Florrie, complaining about her daughters before her husband’s grave:

“…Elva is the worst. You must see how doing the la-di-da with the boys on the road… that Beryl is in bad age now. Yesterday she catch the dog and slowly putting her finger inside and feeling.”

And here’s the Burgher uncle, Cecilprins, coping with family planning:

“’What you buggers doing, men? Elsie, Leah both get daughters and still you sitting here making mallung and cooking fish and no baby coming yet?’

Anna would roll her eyes and say piously: ‘Must wait, no, Papa, until God give.”

Cecilprins would snort. ‘God give? Then what is husband doing?’”

Notice the authorial interjections – notice the measured adverb. Muller himself writes in a prose about a hundred IQ points removed from both Florrie and Cecilprins. The argument for novels in argot, the defence of sloppy sentences in the name of local flavour, can stop abusing Carl Muller now. All the récit parts of the book are evidence of Muller as an artist, an orchestrator of pretty sentences, a manipulator of comic possibilities, and a generaliser of human experience. Here is Muller reaching for the pseudo-anthropological:

“This does not mean that all Burghers were remarkably heterosexual, singularly unambitious, unashamedly incestuous and given without reserve to booze, large families and the principle that tomorrow never comes. The tempora and the mora were an influencing factor. With the British in control, life was good and there was that general feeling of release from long years of Victorian morality and drawing room ethics.”

However, dismissing the scholarly edifices built around The Jam Fruit Tree means that the trip-wires and alarm-systems of literary relativism that protected Carl Muller will also stand defused. This would only offend those whom Muller would love to offend. The writer who celebrated the virility of Sonnaboy for a career cannot possibly be in want of special treatment. In fact, this review would be redundant if it were merely to be a reminder of Carl Muller’s place in the Sri Lankan canon.

But how does The Jam Fruit Tree stand as a novel and as a comedy? How tall does it rise against Brideshead or the Castle of Blandings?

The Literary Audit

The Railway Quarters in Dematagoda, where Sonnaboy lives with his family. Image credit: J.M.S. Bandara/Mapio.net

The truth is that structure is Muller’s easily forgivable flaw. A disconcerting percentage of Muller’s prose is straightforward journalese. Clichés generate clichés like the spread of bacteria. George de Mello has “long spindly legs”, who “is furious, and when George is furious he threw caution to the winds.” Waiting for George to show up, Cecilprins polishes his spectacles “for the umpteenth time.” When things are difficult, they are generally “nigh impossible”. Elva “strikes a pose,” and admires her own “slim, willowy beauty.” And lest we forget, Sonnaboy’s “muscles rippled” when he was in a “fit of fury.”

There are also flabbergasting moments of laziness. For the wedding, Maudiegirl contracts lane women who “were busy in the Boteju Lane home cutting, chopping, basting, baking, roasting, boiling, frying, mixing, mangling, dicing, slicing, grinding, pounding…” That sentence is 11 more verbs long. One wonders why Muller didn’t indulge the technique any further and summarise the whole novel into a running series of verbs, say, ‘drinking, puking, running, fighting, sleeping, drinking”.

Even more damagingly, there are also failures of comedy. Take, for example, the neatly compact joke on page 82:

“Everything, happily, was sorted out in the end. Bertie claimed Elva, Sonnaboy married Beryl and Totoboy married Iris, but before this thrice-happy outcome, Iris and Totoboy suffered injury, Elva was forced to run… and Elaine’s brother’s had to make several visits to the Municipal Outdoor Patients Dispensary.”

The reader sits back with this jumble of mishaps, his or her imagination glorying in the abstract violence, and admires Muller’s technical prowess in condensation. But no, Muller thinks that “it is the duty of the chronicler to add fat and muscle to these bare bones.” The fat and muscle wallow for nearly 28 pages. The effect is that of starting a joke and, instead of moving on to the punchline, elaborating the joke. Elsewhere Muller lapses to the lazy periphrasis of Anthony Burgess (from his hasty books) in lieu of jokes. “Pelvic perambulations” are somehow considered a joke about swinging hips, the Von Bloss girls have funny pregnancies because they are called “abdominal dilations” etc.

The Jam Fruit Tree Lives On

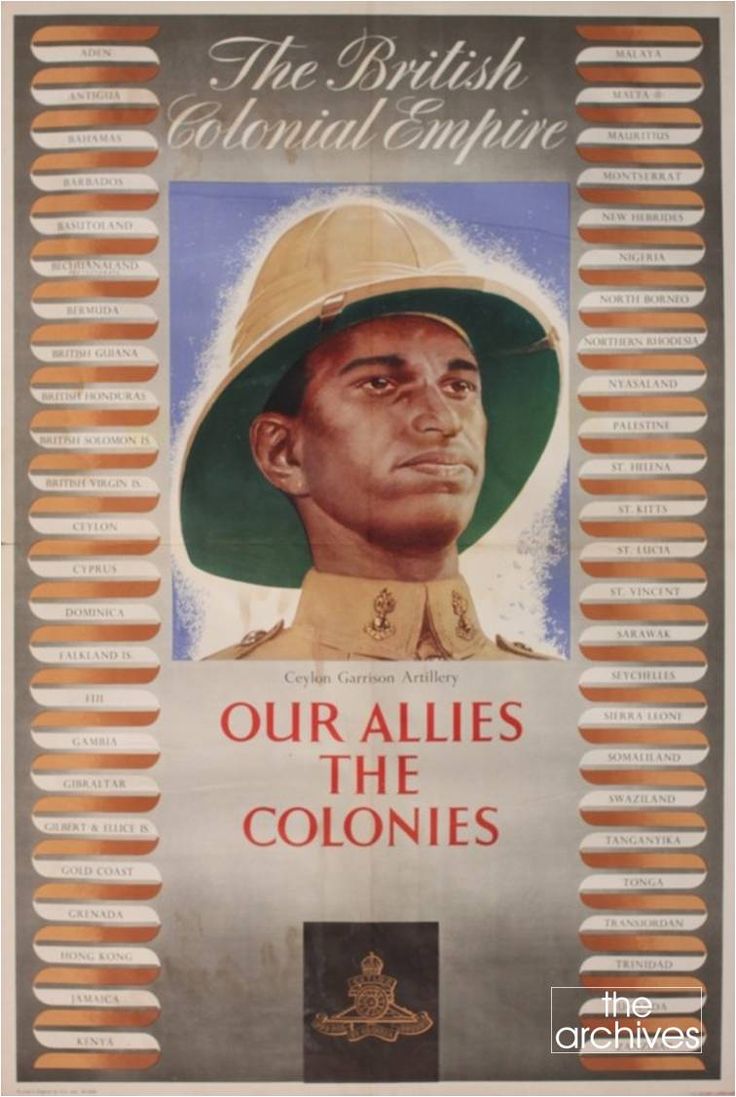

A World War II poster depicting a soldier of the Ceylon Garrison Artillery. Sonnaboy, too, would serve the Queen as a Lance Corporal in the Railway Volunteer Reserve. Image credit: antikbar.co.uk

However, The Jam Fruit Tree is imperishable. Even the cruellest review would not be able to kill it. To every dead branch of literary pretension would be a fresh shoot of bawdry that gives life to the book.

The whole subplot of Eric de Mello, the defeated, asexual momma’s boy, rising to manhood under the Jam Fruit Tree by having his hand thrust between Elsie’s legs, is immortal comedy. The neck-lock that Eric’s momma has him in is in itself an achievement in psychology and understatement.

“Eric would yelp and struggle feebly, then stand still and inhale his mother’s body smell as she whacked him…”

Later, when he inspects his prospective wife up-close, “Eric was positively inflamed. Such a bosom. He could bury his head in that while she beat him and she was welcome to beat him every hour if she wished.”

Eventually, you recover from the Von Bloss appetite and grammar. But long after the Von Bloss experience, you would sigh from your office window, from one of the high heaps of trash that have covered Colonial Ceylon, thinking of the wizened Jam Fruit Tree, and promise yourself an escape into a life of unremitting hedonism. This is all acceptable behaviour. What is unacceptable is to cram the figure of Carl Muller with post-colonial literary theory, to bury his prose as foundation under the establishment of Sri Lankan English, to deactivate the acid in his jokes with scholarly apologies… What is unacceptable is to make Carl Muller behave.

*The Jam Fruit Tree by Carl Muller is available as a Penguin India publication, ISBN: 9780140230314

Featured image: Roar/Nishan Casseem