In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche poses a series of questions that I had always wanted to see, experience, and delve into:

“So he had to ask himself: Have I always labeled unintelligible things I could not understand? Perhaps there is a kingdom of wisdom which is forbidden to the logician? Perhaps art is even a necessary correlative and supplement to scientific understanding?”

From Vendetta to Bend-Data, Muvindu Binoy. Image courtesy writer.

Cinnamon Colomboscope, titled Testing Grounds this year, in its exploration of ‘art and digital culture’ in Sri Lanka, larger South Asia, and Europe, had quite a selection of artwork that not only enhanced the discussions surrounding these topics but also provided multiple façades of perspectives that would have otherwise been imperceptible.

In the post-Snowden/WikiLeaks era of digital technology, privacy takes centre stage in the arena of most heated debates. Professor Urs Stäheli in his talk at Colomboscope went into the depth of the nature of connectivity, different forms of connectivity, and the things that we are connected to. According to him, the two pillars of privacy are as follows:

1) Home/Protection/Possession.

2) The autonomous subject/a return to sociology.

Our homes, the four walls that we always surround ourselves with, give us an unparalleled sense of protection. This protection is something most of us value and guard as our own property and possession; the nature of which the French philosopher Proudhon and dystopian novelist Dave Eggers expounded on in their book What is Property? and The Circle, respectively (the former is recommended by the author to anyone who is interested in anarchism and the latter by Prof. Stäheli).

The unsettling loss of this possession to which our consent is almost always manufactured – in the form of countless agreements that we blindly and hurriedly agree to – was highlighted quite well in the installation Pic-me by Marc Lee. This installation, through an algorithm, selects a location and then selects a post uploaded to Instagram. These seemingly random posts, when accumulated together, posed a series of questions which I found to be disturbing: are these individuals aware that an artist is using their posts to make a statement? If an artist is capable of monitoring data that is posted on the internet, what are multinational corporations and governments capable of? What are the future implications of “randomly” collected data? Where is it stored? Who has access to it?

When posed the question “why do people connect?” and so willingly give into a state of dependence, similar to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Prof. Stäheli had a few interesting answers: on one end of the spectrum we have extremely utilitarian hunger for greater speed, efficiency, and control through “connectivity”, in projects such as Google Loon is seductive across the board, from multinational corporations to individuals; paradoxically, when one commits to such connectivity, because of its nature, one also loses a considerable amount of control. On the other end is the (somewhat) philosophical reason of connectivity for connectivity’s sake; l’art pour l’art; connectivity is its own reason and to some, the thought of needing a moral justification for something as ubiquitous and connectivity is preposterous.

T. Krishnapriya’s installation, Symbols of Power. Image courtesy writer

The ubiquity, technological prowess, and fallacy of connectivity were highlighted in T. Krishnapriya’s installation Symbols of Power. In this installation, Krishnapriya superimposed symbols that denote various modes of connectivity, such as email, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, WhatsApp etc., on inverted pyramids; ancient megalithic architectural feats that awed the world, just like the newest app that enters the market that shows us a “newer” and “better” way to “connect”. And very much like the pyramids, which were built by slaves and housed the dead, we have become slaves to it and given up a little bit of our humanity. We have become zombies looking for solace in a “newer” and “better” way of connecting with each other ‒ while we have forgotten our neighbour’s name.

Ivar Veermäe, in his installation Crystal Computing, brought together aerial images of Google’s largest data centre, which gives us the feeling of transparency and familiarity, and videos of the same data centre, which is surrounded by high security and eludes a sense of inaccessibility and opaqueness. This juxtaposition, I thought, was very similar to the disconnection between the expectations that we have of technology and the “reality” of day-to-day usage of it. Similarly, Mehreen Murtaza’s installation, The Dubious Birth of Geography, underscores this disconnection by placing fictitious geographical anomalies and already existing historical photographs on the same plane.

This leads us to Prof. Stäheli’s second pillar of privacy: the autonomous subject/a return to sociology. The (almost) complete lack of choice that we have to be as autonomous as we wish to be, which can be metaphorically seen in the ridiculous ‘burkini’ debacle in Germany, France, and Italy, and not participate in this supposed hyper-connected world has led us to romanticise the analogous medium and wish to regress to a form of social interaction that did not have this vacuity in our psyches. Imaad Majeed and Muvindu Binoy focused on this romantic notion beautifully in their collaborative song U&IRL. Even in their individual works, Revery and From Vendetta to Bend-Data, the two artists draw attention to how Sri Lankans continue to cling on to traditional ideas of identity and representation and live in a stage of perpetual, regressive, nostalgia.

Emerge + Tech by The Collective of Contemporary Artists. Image courtesy writer

The movie World Brain took this romantic notion to a different level and looked at it from the point of view of an extremely obvious form of “collective consciousness”. Compiled from YouTube videos, fake and real scientific reports, and images on the internet, this film explored various ways in which we can reconnect to nature. Even though it was a little bizarre, the hardware that was used in the movie to connect to the flora and fauna of a forest to create a ‘cybernetic ecology’ and simulate the interdependence of multiple species in a forest showed how far removed we are from nature.

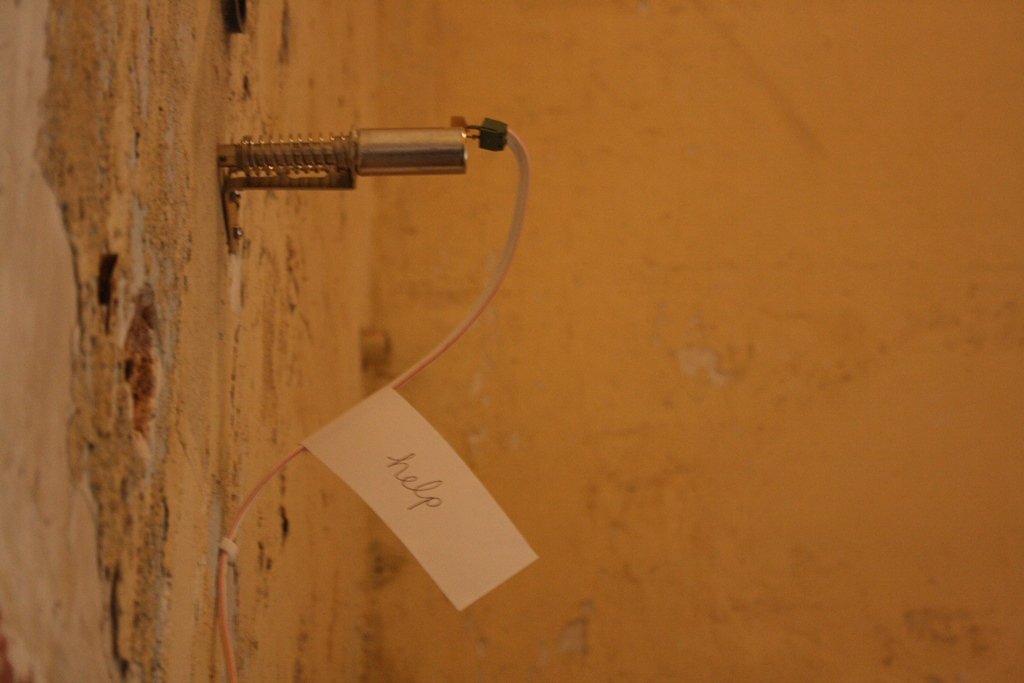

Emerge + Tech recapitulated this sentiment conveyed in World Brain. By installing touch sensitive sensors in plants, The Collective of Contemporary Artists (CoCA), invited us to use the plants as instruments, stressing the important role that nature plays in the human growth and development that we lack in this digital age. Séance by Ali Miharbi, on the other hand, monitored the Twitter traffic between the time zones of India and Sri Lanka for words that reflect day-to-day action such as think, smile, work, eat, help, and so on. And every time the words that were chosen for the installation was tweeted (the artist changes the words depending on the where the installation is being exhibited) the mechanism triggers the device to come into contact with a surface, which in turn, produces a sound. This sound provided a sharp contrast to Emerge + Tech, where the use of the sounds of a glockenspiel to make the return to nature joyous, playful, and reminiscent of our childhood, whereas in Séance the auditory personification of our projections into virtual reality, the projections which expects us to move away from nature, produces, true to the name of the installation, a very harsh and unfriendly sound.

Séance by Ali Miharbi, Image courtesy writer

The Data Detox Bar posed a very perplexing conundrum. What initially seemed like an ordinary Apple store, surgically white, separated from the rest of the artwork, seemed like the least artistic “installation” (if it can be called that) and wasn’t even mildly interesting. The Bar manned by Bobby Soriano and Fieke Jansen, fortunately, did the very opposite of what you would experience in an Apple store. Instead of the buzzwords that are carefully calculated and spewed to entice you to buy at least one of their products, Bobby and Fieke, in just a few panels, workshops, and movies parted with their knowledge on topics that ranged from privacy to the nature of data that, contrary to what one may have expected at first, actually made you ponder. Their alternative app store not only showed you multiple options of applications that are not as intrusive, but also exposed the nature of the functions of the applications that are more popular in the market. The white surface of the bar ended up being where various shades of knowledge were imparted.

Gaze by Arash Akbari. Image courtesy writer

My favourite installation at the festival, was, by far, Gaze by Arash Akbari. More often than not, an artwork becomes as much about the artist’s ego as much as the work itself. By creating an algorithm that can be used in almost any device, which distorts footage from the camera and sound from the microphone that is rendered back to the screen, the user becomes both the subject and the artist. This installation resonates with works such as Imaginary Landscape by John Cage and has almost completely removed the ego of the ‘original’ artist.

(De)Generative Processes II was easily the climax of Cinnamon Colomboscope. Using the dome of the Sri Lanka Planetarium as a canvas, Asvajit Boyle and Lalindra Amarasekara projected a psychedelic array of lights, music, and movement. What was initially planned to be an audio reactive performance had to be scrapped due to bureaucratic impossibilities and the duo had to improvise with the available resources. It was nevertheless a mindblowing experience. The heavily processed music was sequenced and synchronised live to the visuals in order to emulate the nature and feeling of the sounds that were used. I highly doubt anything of this calibre has even been attempted in Sri Lanka before and I have no doubt that, if they were to perform regularly, people would be willing to pay to watch the duo work their magic!

Overall, Testing Grounds presented Sri Lanka with an extremely complex labyrinth; a labyrinth of walls that were decorated with ideas that were framed with an artistic flourish; flourishes that were further elaborated on with multiple discussions and interlinking paths of movies and performances, in which I have stumbled upon only one path. I wonder what other paths the rest of the audience came across… or maybe they just gave up, turned around and left. Maybe that was intended path…

Featured image: From Séance by Ali Miharbi. Image courtesy writer.