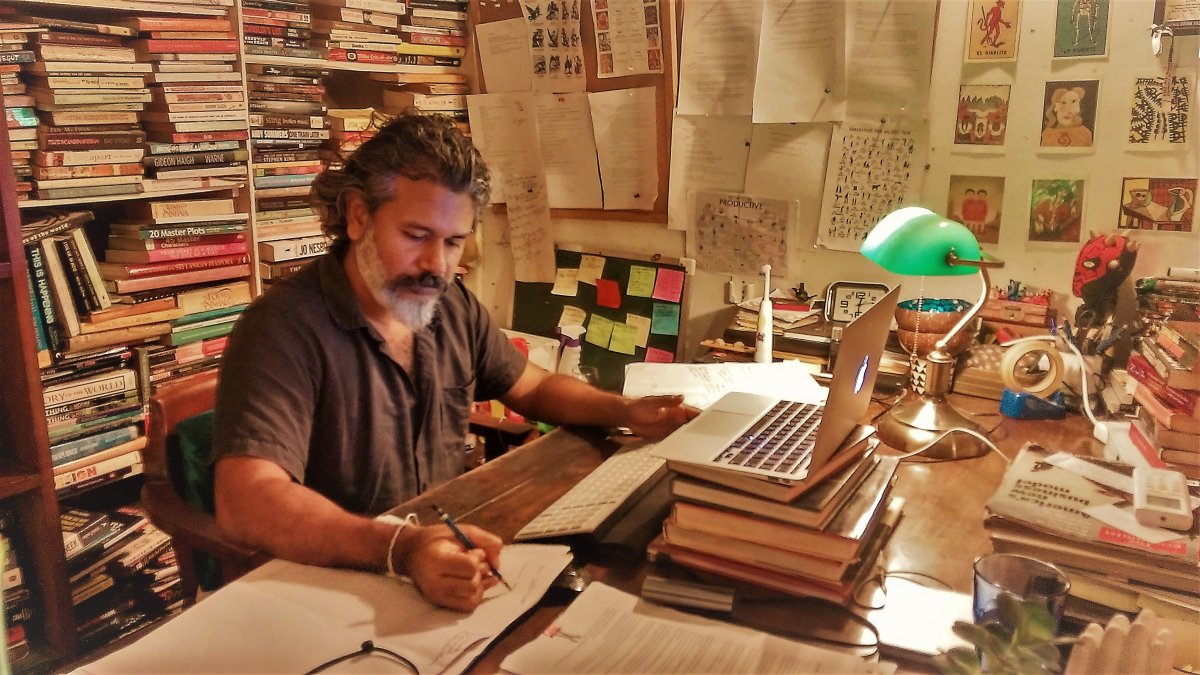

Two questions in, before we could even calibrate as interviewer and interviewee, Shehan Karunatilaka’s daughter marched into the room, with her two-foot high smile of superiority, and had this settled for good: Elmo, as well as the herd of stuffed animals on Karunatilaka’s sofa, was hers. After placating her (he just betrayed Elmo into her custody), Karunatilaka closed the door and fortified it with a stool. This really is the everyday Colombo Dad with his casual shorts and his vendetta with mosquitoes. He is also the author of award-winning novel Chinaman.

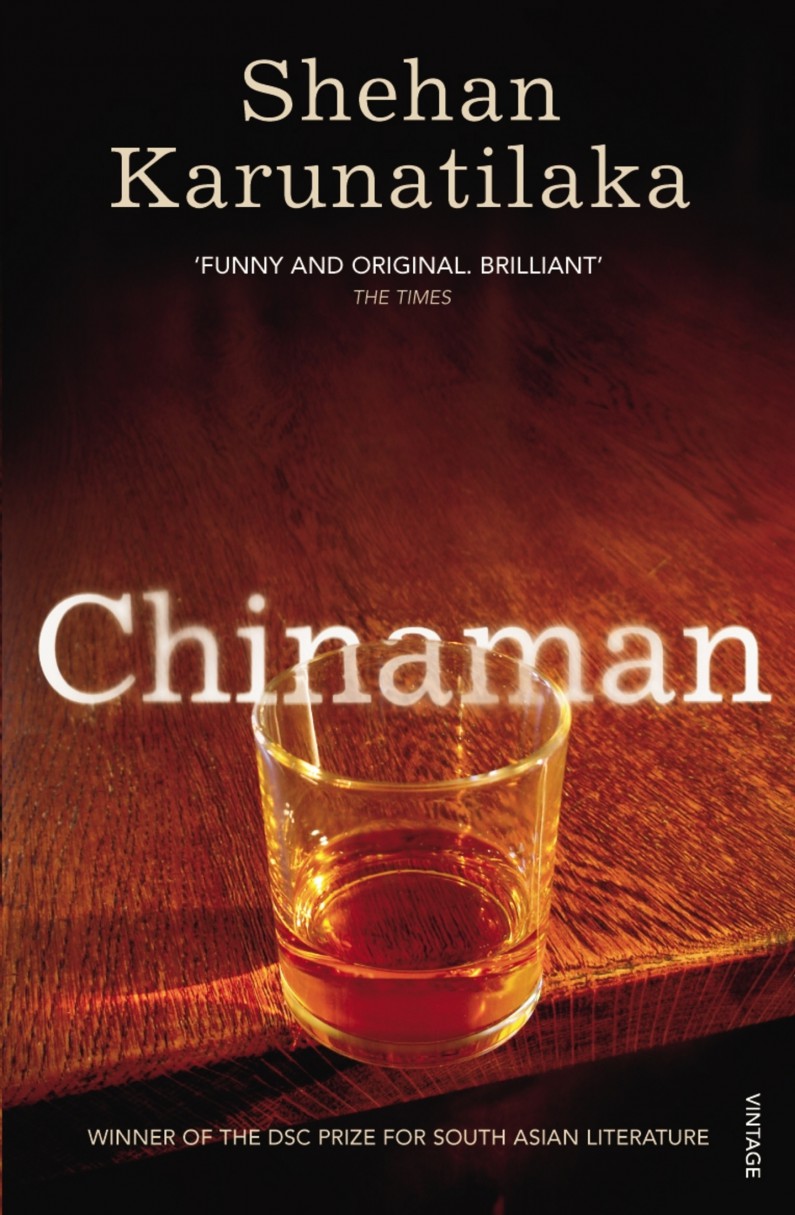

Before Chinaman won the Gratiaen Prize in 2008, the average Sri Lankan English writer practised literature the way the average Sri Lankan drinks tea. Over-sweetened with sentimentalism, brewed in a rush, and half consumed for the sake of politeness, Sri Lanka’s English novel was an unconvincing imitation of a colonial habit. There were exceptions in candour, like Carl Muller’s The Jam Fruit Tree, but not exceptions in craftsmanship. Winning both the 2012 DSC Prize for South Asian writing and the 2012 Commonwealth Book Prize after the Gratiaen, Chinaman is to Sri Lankan writing what the 1996 World Cup is to Sri Lankan cricket.

Every year since, we have been expecting Karunatilaka’s next novel, and have despaired when Gratiaen shortlists failed to come up with it. Finally, this year, Karunatilaka submitted a collection of short stories titled Short Eats for the prize. Roar met with Karunatilaka to discuss his journey since Chinaman.

What do you think about short stories as a medium? Do you feel like it’s an excursion from your novelist’s role, or is it a parallel career for you?

I think it’s a completely different ball game. I’m quite new to it, and I’m still learning. I have been working on this very big novel called Devil Dance, on and off, for about three years. So I enjoy doing a short story, where it’s usually just about one thing, as a break from writing novels. Novels are rarely about one thing. In short stories, it’ll be one idea, one character, or one situation. But yeah, I’m much more comfortable doing novels than short stories.

Shehan Karunatilaka’s award-winning novel Chinaman. Image courtesy: Random House Australia

What difficulties did you face adjusting to short stories from novels?

The difficulty I am finding now is with controlling tone. With a novel, you get time to live with a character or story. By the second or the third, or fourth or fifth month of writing, the tone just comes naturally. With short stories, you have to invent that tone very quickly, and each story may have an individual voice that is not interchangeable with that of another.

Also, with the types of novels that I write, I can ramble a bit and go all over the place without wasting my reader’s patience. With a short story, you can’t really do that. You have to be focused on what the plot is, what the characters are doing, what they want, and how it’s resolved.

Let’s get to novels. What is your method of composition? Do you write headlong, nosedive? Or do you write a synopsis or plan out a plot?

I think when you are starting you don’t plot too much. You start with an idea, a situation or a conflict and write yourself into a corner, where you don’t know what will happen next.

Theorists have divided writers as gardeners and architects. The architects will draw the blueprint, know exactly which piece goes where, which chapter, what character does what. So they’ll spend about six months on the blueprint, making sure it is perfect. Only then would they commit themselves to writing. A lot of screenwriters do it that way.

Then there are the other writers who are called gardeners because they plant a few seeds. They don’t know what will come out of it. They suddenly say, oh, I thought it was a mango tree, now it turns out it’s a strawberry plant. So what do I do with this? That approach is scarier because you don’t know where you will end up. With Chinaman, that’s how I started. I just thought about a drunk man sitting in a pub talking about cricket. But then what happens is a plot emerges from that. Midway through the book, which is where I am with my second novel, you make a loose plot. In the process, you also get a lot of stuff that you don’t use, you take paths that don’t take you anywhere. So, I guess I’m bit of both gardener and architect.

If novelists can be divided into plot novelists and theme novelists, where do you think you belong? For example, a plot novelist would construct the story out of the relationship dynamics of characters, whereas a theme novelist would bend the story to keep on the theme.

I wasn’t aware of this separation. So who’s an example of a theme novelist?

Ok, theme novelist, say, Anthony Burgess. You’ve read A Clockwork Orange? He starts out with an idea. What’s good and evil, is it better to have free will.

And a plot novelist would be your typical thriller writer. Right. I’m probably a plot writer. I think that’s the mistake I made with the second book. The first book, I started out with the plot in mind. The theme emerged through the writing. It’s only towards the end—when I knew what the plot was—that I realised that the book wasn’t really about cricket. It was about fathers and sons, failed genius, how Sri Lanka was like Pradeep Mathew, who had had all the talent and squandered it. I finished the first draft, went back and enhanced the theme.

With the second book, Devil Dance, I started out with a theme and not much of a plot. This is why it’s taken so long. The theme was fine but the story meandered. Personally, the stuff I respond to is literature that makes you hang on, wondering what happens next. They make you forget that you are reading a story and immerse you in the drama. Only later would the themes hit you, and you realise, ok, now that’s what this was about.

Shehan Karunatilaka posing with the DSC Prize and, to his left, the Queen Mother of Bhutan, Ashi Sangay Choden. Image credit: Getty Images/Prakash Singh.

Speaking of Anthony Burgess, it was he who came up with this division of the A writer and the B writer. The A writer is primarily a storyteller. The B novelist is a language stylist. Where would you fall?

You’d like to fall in the overlap. But I think I’m guilty of being a B novelist, a language novelist. I do spend a lot of time crafting prose. I mean, it’s a difficult thing to do, and I do enjoy beautiful writing which doesn’t necessarily have a plot. But the storytelling, the plot, I find harder. The beautiful sentences come easily to me.

When constructing scenes, do you go like a theatre director, first doing a mise-en-scène and a roll call of characters?

I tried the mise-en-scène at the beginning. My technique is still evolving, and I don’t know if I can say I use one technique in particular. In the beginning, I do waste a lot of time doing a plan of the room, deciding what colour the curtains are, getting to know the characters and their backstories, their favourite cartoons when they were kids. Writing is a lot of displacement activity, so you need that. But I don’t do too much of it. Ultimately, you have to realise what’s the purpose of this scene and what this particular character wants from another. Sometimes a little distraction is good, too. It’s good to stop paying attention to the characters for a bit and describe the cat that’s running around. It’s a bit cheesy if the point of the scene is on the nose of the reader.

What’s your method of revision? Do you finish a sentence and then rework it before the next one? Or do you finish a chapter and then go through it?

I revise all the time. Sometimes too much. I’ll first write it to the end. For example, I wrote this in the morning, got to the end of it. It’s a mess, but I got the main purpose of that scene down. I’ll probably spend this week, as a procrastination method almost, and go back and do the editing and revising. Then I’ll leave it and move on.

You edit for different reasons. For example, now I’m editing for tone. Sometimes I realise that the subplot is getting in the way of the main plot. For me, there can never be too much revision. It can only make it better.

Shehan Karunatilaka in conversation with Dileepa Abeysekara, the Sinhala translator of Chinaman. Image courtesy: Youtube/Smart Annual Report.

What do you think of overwriting?

Maybe I’m guilty of that. But I’d rather overwrite than underwrite.

Let’s take a specific case. What do you think of Arundathi Roy? She’s always accused of overwriting. Do people confuse overwriting with style? And the absence of style as clean writing?

I’m a big fan of The God of Small Things. It was a divisive book even though it was highly successful. For me, the story had the language it needed, and it worked brilliantly.

Some people think Salman Rushdie’s prose is too chocolatey. I read all his early stuff, and I didn’t mind that I spent extra time on the page. It was lovely writing. He’s still got plots and all that, but then he likes to spend time on details and expand on them for a few pages. Anyway, I don’t believe in this overwriting/underwriting division. I think there’s just boring writing and exciting writing. If you are engaged, the prose is successful.

What’s your work ethic? Do you do nine-to-five on a book?

Oh yes, that’s changing, since the kids came along. In Chinaman-days, I used to write from 4:00 a.m. to lunchtime. When you are writing, you have to write every day. The story reveals itself to you when you write every day.

That was a good system. Now it’s a bit tougher. As you can hear the wailing –

(In the next room, Elmo is getting an earful)

Yeah. Let’s talk about prose style. You spoke about Raymond Carver, the exemplar of minimalism. Where do you think you fall in the spectrum between maximalism and minimalism?

My sentences are quite short. I think that’s the advertising influence. Advertising is what I do for a living. The two texts that I always give junior copywriters working under me are Hemingway and the Bible, regardless of what their religious beliefs are. Other than a few adjectives here and there, the Bible reads like, “God created earth”. I suppose I start out in that minimalism when I plot the book, but I like adding a few flourishes here and there. This is my current gym workout—

(Walking to his shelf, Karunatilaka pulls out two massive blocks, which he begins lifting up and down like dumbbells—a compendium of Hemingway on one hand and Douglas Adams on the other.)

This is Hemingway’s journalistic work. It’s just reporting, but then again it’s very macho and stylistic. Douglas Adams is talking about life, the universe and all these big concepts, but using absurdity and humour. If you are just doing the minimalist style, endlessly Hemingway, it can be a bit humourless. I always read something minimal and something maximal at the same time. I don’t know where I fall in the spectrum.

Remember what we talked about A novelists and B novelists. Do you have A influences and B influences? Are you reading Douglas Adams and Hemingway for different reasons?

I grew up reading Agatha Christie and Stephen King. I still read a lot of Stephen King, for plot. His voice is very different, and it’s all in the service of the plot. I do consciously alternate my reading between A writers and B writers. Now that I’m reading Stephen King, I would next read John Updike.

I read Kurt Vonnegut for pleasure. A lot. And I read a lot of him when I wrote Chinaman. Now that he’s passed away, I only allow myself one more of his books, because one day I’m going to run out of his books and that would be a sad thing. I don’t know if you would call him a plot novelist. I guess he’s a B novelist.

Of Sri Lankan writers, I admire Romesh Gunesekera and Michael Ondaatje. They are both great prose stylists, very similar in their outsider look at Sri Lanka. As far as plot goes, there’s a lot of plot in some of their stories, not so much in others. I think more than them, Carl Muller opened up more doors for me. I don’t think he’s ever accused of being a prose stylist. Some of his later work is just spontaneous. However, I was drawn to it. The idea that you could write about these domestic squabbles and how people talk—it was liberating for me. You can see Carl Muller’s influence in Chinaman.

I guess Kurt Vonnegut is who I read consciously. When I was getting into Chinaman, and I wanted this voice of sad, all-knowing old guy.

A contestant for the Gratiaen Prize of 2016, Vivimarie Vanderpoorten addresses the gathering. This year’s chair judge of the Gratiaen Prize, Sasanka Perera, sharply criticised double standards and the lack of ambition that’s holding English writing in Sri Lanka. Image credit: Chandana Dissanayake.

Whenever someone complains that Sri Lanka has not produced enough good art, the excuse is our industry is immature and that our canon is still too young. Do you think writers are a collective industry or just individuals?

People self-publish here, a lot. For a couple of lakhs you could print a run of about 1,000–2,000 books. A mature publishing industry will edit a book, tailor it to a specific market, and then market it. We don’t have any industry by any stretch—I mean, I can count our publishers on one hand. What we have are a few writers who are all doing other things to make a living. We might take a few months off and write a book. We are all amateurs here. To write something of international value, we have to become professionals, and write every day.

However, I think these are also excuses. Writers don’t need to wait for an industry to produce a good book. We have internet, we have access to libraries—we have all the resources that Hemingway had. And we certainly have the stories. Even when I’m struggling to write my second novel, what inspires me is that we have this abundance of stories. You just check the Sunday newspaper, there will be an idea for a story. You just scan our last thirty years, or last three hundred, or three thousand years, there’s a lot of fresh, untold stories. With Short Eats, that’s what I tried to do: I dug deep and found some unusual stories.

This question about Sri Lankan writing was raised by Sasanka Perera, the chair of the judges at this year’s Gratiaen Prize. He gave a real hammering speech and demanded why we are just giving each other awards while, you know, forgetting to write good books. I agree completely with what he said. I think the onus is on the writers.

How do you think the pressures of politics influence you? How important is freedom of speech and the guarantee of safety, as a fiction writer? It is a given about journalists.

You seem to be able to get away with a lot more with fiction than you would with journalism. Even when journalists were getting killed, we still had Puswedilla on the stage and Always Breakdown on the TV. We seem to have tolerance of satire. Maybe the powers that be feel secure knowing that it’s just a Colombo-centric thing. Maybe if Puswedilla was staged all around the country in Sinhala, they might have got worried. Even when our freedom of the press was crushed, art seemed to get by. Maybe this was a sad thing because the powers that be thought art has no political power.

A few of the short stories in Short Eats, I wouldn’t have written ten years ago. But now I feel more emboldened to write about politics and political families. Also, that’s another reason why I chose to write about cricket and arrack when I wrote Chinaman. I thought perhaps I could write an innocent book about two very Sri Lankan things that wouldn’t get me into trouble. People were still worried that cricketers might take offence to this. But I fictionalised, or disguised it enough so that multiple people took offence, not just one powerful person.

I don’t feel nervous about publishing Short Eats in the current political climate, but you never know. Things change in this country so fast. But we all know what happened to Salman Rushdie, and no one would envy that.

The question is really about self-censorship, because the fiction writer usually doesn’t have anyone telling him or her what to write, but it’s the writer who does it on his or her own.

I would like to think I go where the story takes me. But yes, I know the reality. I do my work in Singapore, and that’s the capital of self-censorship there. They have a lot of funding there, but not much art. Maybe it’s because you need a bit of dirt to create good art. All the great music has come out of the dodgy part of town, born out of some conflict, from some grievance with society.

Self-censorship can be a very dangerous thing. Chinaman was harmless, and Short Eats, I think, is okay. It’s a question I may have to tackle with my next novel.

Karunatilaka’s Short Eats is still in manuscript form and Karunatilaka may edit the stories further before release. As of now, the book consists of 13 short stories and 13 very short stories, which Karunatilaka describes as flash fiction. He promises that it will have a mix of genres, some of the stories belonging to science fiction and some inspired by action movies. There’s even a story told entirely through Facebook posts. “So I’m just kind of mucking around,” says Karunatilaka, “trying things”.

Featured image courtesy writer

.JPG?w=600)