If you grew up in the ’80s or ’90s, one thing you could never forget in the bleak wasteland that was television, was the series of cartoons dubbed in Sinhala. You would sooner forget to eat than to forget when Dosthara Honda Hitha came on the telly. Or Pissu Poosa, Haa Haa Hari Haawa, or Gulliverge Suwisariya. Not to mention the wonderful dubbings of Robin of Sherwood, Kung Fu, and the classics like Les Miserables, which was adapted as Manuthapaya. None of these was a local tale. Yet, the dialogues were rewritten in Sinhala and then dubbed with such a proficient skill in language that they might have been local folk tales all along. You might even find someone who lived a lifetime never realising that these weren’t made here at home. The man behind all this was the beloved “Uncle Ti”: Titus Thotawatte.

Titus Thotawatte’s career began at the Government Film Unit (GFU) where worked on documentaries as a film editor. He even edited a few documentaries by the great Lester James Pieris, with whom he forged a great friendship. A few years later, these two and cinematographer Willie Blake would leave the GFU to make their own movie: Rekawa. It was a revolutionary film on many fronts. Rekawa was the first Sinhalese film to be shot fully in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) and the first local film to be filmed outdoors, on location. In those days, films were shot on a closed studio set. Rekawa was the film that changed all that. All previous Sri Lankan movies had been remakes of Indian cinema.

After that, Thotawatte used his editing skills on many great movies, such as Parasathumal, Ran Muthu Duwa, Gatawarayo, Hanthane Kathawa. He also tried his hand at directing. Chandiya, starring the great Gamini Fonseka, was released in 1965. Then followed Kauda Hari (1969), Thewatha (1970), and Haralaksaya (1971). But his most famous film is the children’s drama Handaya (1980), which is still loved to this day. Thotawatte’s films were lauded for showing true-to-life characters instead of the caricatures who were often cast in cinema for dramatic effect.

His greatest impact on Sri Lanka’s media landscape came after he joined the Rupavahini Corporation in 1982. Here, he produced an array of insightful, educational, and entertaining programmes. His maiden teledrama Ran Kahawanu boasted an all-star cast from his days in the cinema, but it failed to gain much popularity. Thotawatte also tried his hand at educational programming like the economics-focussed Ganu Denu. Then he turned to another source: programmes from outside Sri Lanka.

The cartoons dubbed into Sinhala are arguably his most beloved achievement. Taking animated shows of legendary western characters such a Bugs Bunny from Looney Tunes, Top Cat and Dr. Doolittle, Thotawatte created completely localised characters by simply changing the names and dialogues. He even used colloquial Sinhala, which made them even more relatable. Dr. Doolittle became the good hearted Dosthara Honda Hitha; Top Cat became the crazy Pissu Poosa; Bugs Bunny became Haa Haa Hari Haawa—which comes from a well-known poem about a rabbit by Kumaratunga Munidasa. He also made sure to use the best talent available to him. For example, The Grasshoppers band in Dr. Doolittle became the La Thanakolapeththas, and for their songs, he enlisted the beloved and talented writer Premakeerthi de Alwis. The songs written by him, with music by Somapala Rathnayake, such as Muhuda Mage Godabimayi, Kapili Ketili Kelam are still so much a part of the people that you are guaranteed to hear them at any paduru party. It’s after these that he started being known as “Ti Uncle”.

Ti Uncle didn’t stop with cartoons, though. He applied his skills to live-action imports as well. Malgudi Days, the famed television adaptation of R. K. Narayan’s books by Shankar Nag, became a hit here after a treatment of dubbing by Ti Uncle’s hands. R. K. Narayan had once described Malgudi as a town “inhabited by timeless characters who could be living anywhere in the world.” Nothing proves this more than Malgudi Days dubbed into Sinhala. Ti Uncle managed to retain the essence of the characters and still make it relatable to Sri Lankan audiences, the language barrier notwithstanding. But sometimes he stopped at subtitles only. Robin of Sherwood and David Carradine’s Kung Fu only received subtitles. But that didn’t stop them from becoming popular. While something like Malgudi Days would have a lot of overlap with Sri Lanka and thus be easier to relate to, making tales like Robinhood connect to Sri Lankans without breaking character is a laudable achievement. However, Ti Uncle’s most beloved effort came from a culture that was even more alien than that.

Oshin was a Japanese serialised drama that aired on NHK from 1983 to 1984, and told the story of the life and eventual success of its plucky heroine, Shin Tanokura. Its surprise success in Japan led to it becoming a global hit, being exported to many countries. So much so that the word ‘Oshin’ even entered the local idiom. Thanks to Ti Uncle, one of these countries was Sri Lanka. With a stellar voice-over cast to aid him, Ti Uncle brought the hardships of the Meiji Era into our homes and made them relatable. Oshin was lauded as not only an entertaining protagonist, but as an example of good character as well. It had its umpteenth rerun on Rupavahini not too long ago.

That’s because Sri Lankans have never complained about their media consumption more than they do now. It’s hard to find someone today who will say television adds value to their lives. The hours of operation are longer, the number of ads higher, but the quality doesn’t seem to have followed the money. In fact, recently, the Rupavahini Corporation started finding great success with reruns of their teledramas from the 1980s and ’90s. These programmes proved that they are still loved, and found new fans even today. How did the industry fall this low? The usual suspect here is the Indian mega tele-serial. Because it’s cheaper to import and dub rather than produce new material, these dramas are very attractive to TV channels. With their melodramatic plots, over-the-top acting, fast cuts, extreme close-ups, and high production values, they are as addictive and unhealthy as a sugar rush. The terrible dubbing will instantly make people—who know better—think of a time, and a person, who made foreign imports something to look forward to.

Refined tastes such as Ti Uncle’s are greatly missed in the current television landscape. His death in 2011 was a loss that seemed impossible to fill. Although later dubbing maestros such as Rupavahini’s Athula Ransirilal and Sirasa’s Gaminda Priyaviraj and Suneth Chithrananda came quite close, they were never the same. Television programming today seems to be made for shock-value and not truth value. So it’s no wonder that people are nostalgic for simpler times when a programme opened with a black and white picture of a jolly, bearded gentleman and you knew for sure that your next half hour would not be a waste of time.

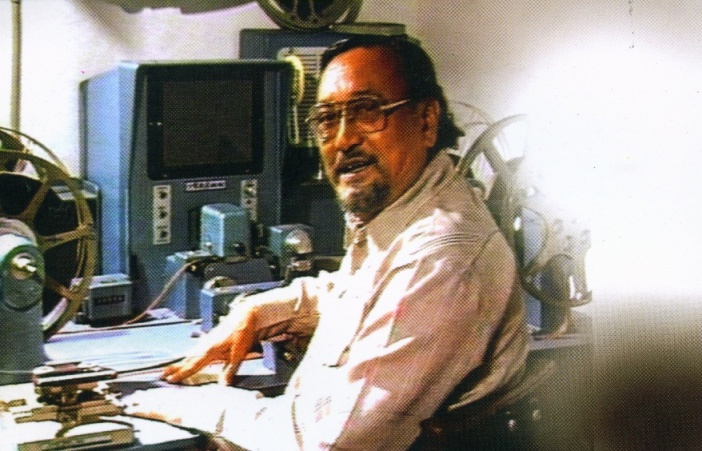

Featured image courtesy biography by Nuwan Nayanajith Kumara