Modern Sri Lanka’s most significant political attempt at finding a lasting solution to tensions between the two main ethnic groups — the Sinhalese and the Tamils — was the Indo-Lanka Accord of 1987, which, among other changes, introduced the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. The amendment has come into sharper focus recently, with President Ranil Wickremesinghe promising a full implementation that has been avoided by previous leaders.

The Tamil National Question

Tensions between the Sinhalese and Tamils increased as the country struggled to find footing after independence in 1948. The Ceylon Citizenship Bill of 1948 left Tamils of Indian origin in the country stateless. In 1956, the ‘Sinhala Only’ Act made Sinhala the official language and the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact in 1957, which promised more regional autonomy to the provinces, was abandoned a year later. Anti-Tamil pogroms in 1956, 1958, 1977, 1981, and 1983 darkened the decades following independence and by the late 1960s, numerous Tamil rebel groups had formed, demanding a separate state, with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) eventually emerging as leaders of the armed struggle.

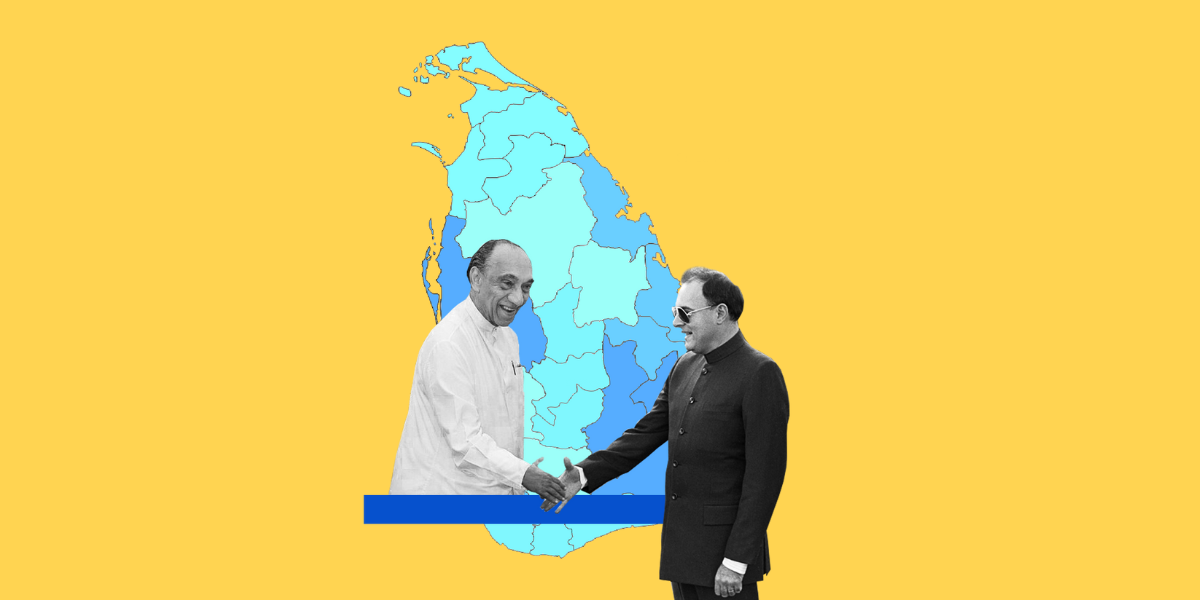

Indo-Lanka Accord

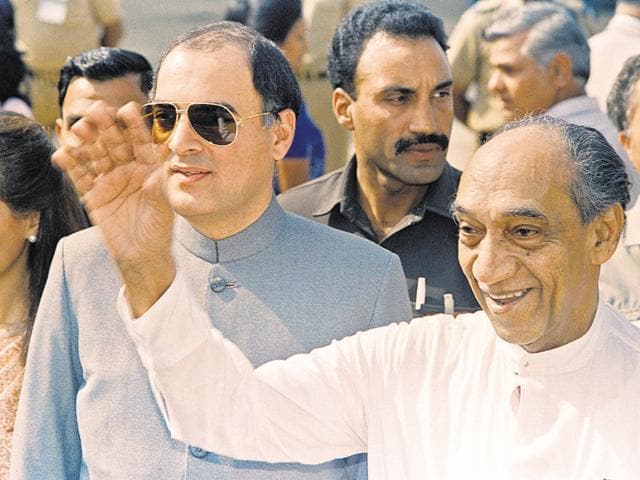

The events of Black July in 1983 resulted in nearly 100,000 Tamil refugees in Tamil Nadu, India, which was the justification for Indian intervention in Sri Lanka. Although separatism was never the goal, India intended to mediate a lasting political settlement with the J.R.Jayawardena-government.

On 29 July 1987, the Indo-Lanka Accord was signed between President Jayawardena and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi of India, resolving that:

- Hostilities be ceased

- Sinhala, Tamil, and English be the official languages

- Provincial Councils elections be held

- For India to ensure that the Indian territory is not used for activities prejudicial to the unity of Sri Lanka

- An Indian peacekeeping contingent be invited to enforce the cessation of hostilities, if required

The Accord was to be enacted following an amendment to the Constitution. The 13th Amendment to the Constitution was passed on 4 November 1987, creating the Provincial Councils.

A Controversial Resolution

The Indo-Lanka Accord was significant as it officially acknowledged that modern Sri Lanka was a ‘multi ethnic, multi lingual, pluralistic society’ and that the Northern and Eastern Provinces were areas which the Sri Lankan Tamil-speaking peoples had historically inhabited. The resolution also resolved to preserve the territorial integrity of the country by achieving a political settlement and ending armed struggle.

However, analysts have noted that it was these very factors that led to opposition against it, by both Sinhalese and Tamil hardliners, but for very different reasons. These acknowledgements of history and pluralism are in direct opposition to those who propagate a Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarian state. Tamil separatists also view the implementation of the 13th Amendment as an end to achieving a separate State.

“Sinhala nationalists argue that the 13th amendment could lead to a separate State while Tamil nationalists say that the 13th amendment does not go far enough, in terms of devolution. There is no real value in these arguments. The 13th Amendment is very clear about devolving particular powers,” Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) Senior Researcher and Attorney-at-Law Bhavani Fonseka told Roar.

India’s hegemonic power and actions in the lead up to the Indo-Lanka Accord and in the years following it have contributed to the suspicion surrounding the 13th Amendment. Tamil militant groups ran propaganda offices from Tamil Nadu while allegations of training and arming them on Indian soil remain. Moreover, India encroached on Sri Lanka’s airspace in June 1987 to drop food parcels on Jaffna, when the Sri Lankan armed forces were close to defeating the LTTE after the military operation in Vadamaratchy in May 1987.

The Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), later even dubbed the ‘Innocent People Killing Force’ has severe allegations of crimes against civilians, including murder and rape. Although people in the North initially welcomed them, the LTTE quickly turned against the IPKF and the IPKF left the country in 1990.

The South furiously opposed the IPKF and the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), in particular, operated against the IPKF in Trincomalee during their second insurrection.

The 13th Amendment (13A)

13A created the Provincial Councils, where all nine provinces share power and self-govern through provincial administrations. The amendment created the Provincial Council List, the Reserved List, and the Concurrent List. Government subjects and functions such as education, land, housing, and police, have been divided among the three lists.

However, restrictions on financing and contentious politics have meant that the devolution of power has not been very effective. In particular, the provisions regarding police and land powers have never been implemented.

“The provisions regarding land and police powers have never been implemented. It remains to be seen whether the amendment is functional when done so. The larger concern has always been about the police powers and what it means in terms of security. However, if you look at the constitutional framework, it is very clear about the exercise of powers within the province. I believe these are misguided concerns. The 13th Amendment should be fully implemented because it is the law of the land,” said Fonseka.

Police powers are devolved to each province under the 13th Amendment, by setting up the National Division and a Provincial Division for the police force, with the IGP remaining as the head of the entire force. However, this does not include national defence, national security, use of any armed forces, or any other forces under the control of the government in aid of the civil power.

“Sinhala nationalists use these points about police powers to say that it could lead to a separate State. However, they never articulate how that process would be. This noise and rhetoric is enough to create fear about the amendment in certain sections of society,” noted Fonseka.

The Provincial Councils reserve land rights, land tenure, transfer and alienation of land, land use, land settlement and land improvement, subject to other special provisions. This does not include state land.

Proponents of a Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarian ideology have continued to oppose the devolution of power to the Provincial Councils, citing reasons such as Sri Lanka being too small to do so and speculating on the threats of federalism and separatism.

Old fears about the 13th Amendment are being freshly dug up as President Ranil Wickremesinghe reiterates his intention to implement the 13th Amendment. However, his intentions are being questioned with some noting that it could be a false promise to garner the minority vote in upcoming elections.

.jpg?w=600)