For more than a decade, multiple invasive fish species have been released into natural waterways in different parts of the country — posing a threat to endemic species.

Despite the existence of government-imposed bans that seek to control exotic fauna and flora being brought into Sri Lanka, for years, experts have complained that specimens are still being smuggled into the country. On multiple occasions, exotic fish species — originally brought down to be sold as pets to enthusiasts or to be showcased at aquariums — have even been released into the wild (either intentionally or accidentally), resulting in threats to local ecosystems.

Now, as a result of trade and breeding resulting from a fascination for ‘monster fish’, threats to endemic freshwater species have only increased. In spite of the COVID-19 pandemic and its resulting restrictions, some experts say that negligence and political influence have led to a continuation of behaviours that contribute to these threats.

Monsters Vs Aliens

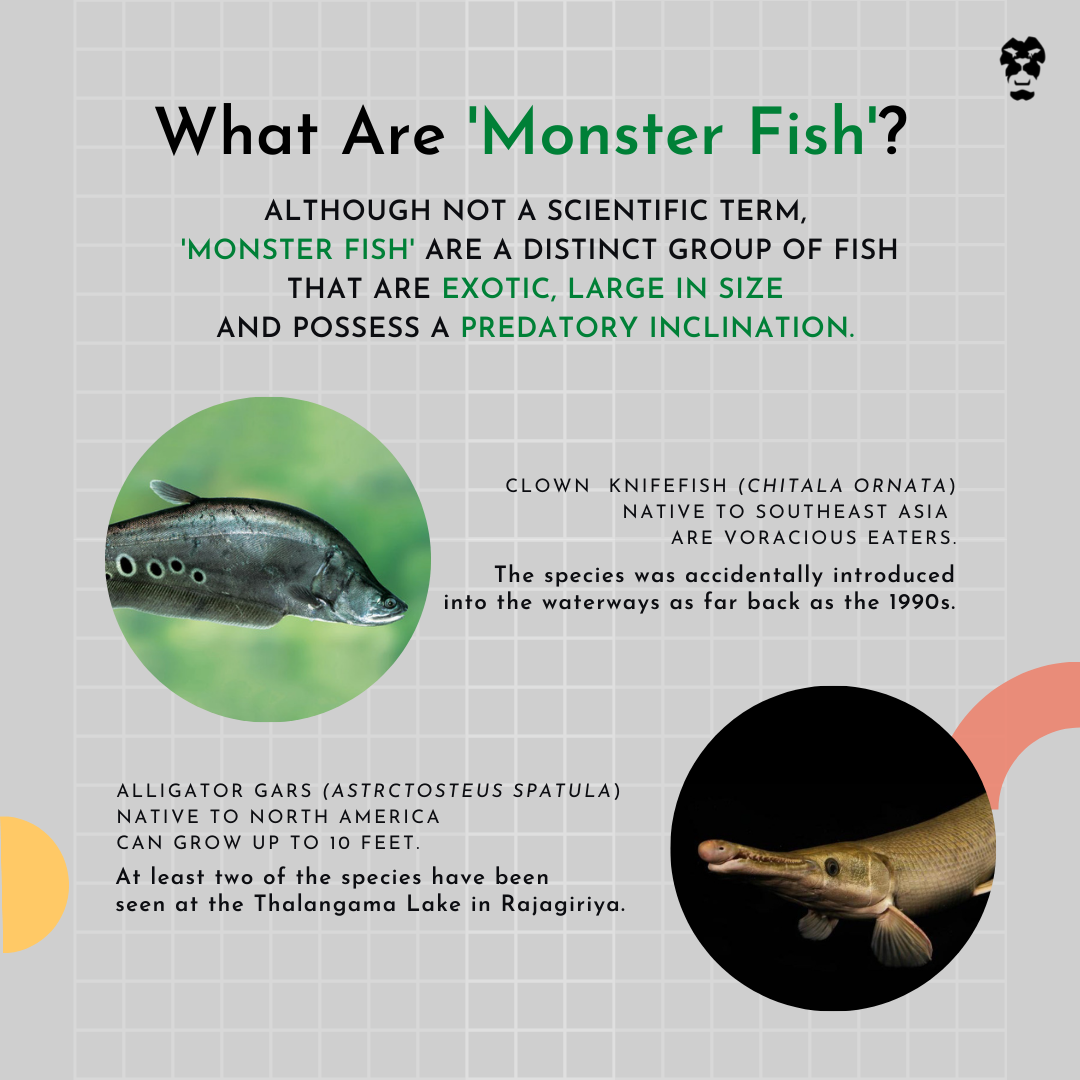

‘Monster fish’ have gained increased attention in the last decade. The term does not refer to one specific species; rather, this is used to describe large, exotic and often carnivorous fish, which are immensely popular in many commercial Sri Lankan aquariums. Multiple Facebook groups that have been created to spread information among enthusiasts — latest species on sale, where to buy fish food and tanks — attest to their popularity.

According to Sampath De Alwis Goonatilake, project manager for the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) and resident freshwater fish expert, the term ‘monster fish’ describes carnivorous and aggressive fish species, many of which might not even be invasive. “For example, eels can be considered monster fish because they are aggressive creatures. But they are not particularly invasive,” he explained.

On the other hand, invasive or ‘alien’ species are also voracious predators, and severely territorial — the tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus and Oreochromis niloticus), during mating season, bury their eggs in the bottom soil of lakes and guard it, allowing nothing to approach; those who have the misfortune of drifting close would be viciously attacked — including creatures that may be endemic to Sri Lanka. While tilapias are not, strictly speaking, ‘monster fish’, they are by all accounts invasive species that are not endemic to Sri Lanka. They were introduced artificially in 1952 in order to enhance freshwater fish production — those who bred tilapias could sell their meat. However, tilapias have now become a dominant group of fish in inland water bodies.

As for the much-sought-after monster fish, one vendor told Roar Media that depending on the species, their prices can vary. At five inches in length, a clown knifefish (Chitala ornata) that is known to prey on everything from smaller fish to amphibians, insects, and crustaceans, sells at LKR 700; larger specimens, while more expensive, were out of stock.

A variety of six-inch-long gars known as rocket gars (Ctenolucius hujeta) sells at LKR 5,000. The vendor claimed that he only sold imported species. A similar species, the spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) at 17 inches, sold at LKR 25,000.

Despite their availability in the market, none of these species have been brought to Sri Lanka legally, according to retired deputy director of the Sri Lanka Customs, Samantha Gunasekara. “All of these species have been smuggled into the country. Even if they say that fish have been imported legally, I can guarantee that they have not received the necessary permits to do so,” he told Roar Media.

“In the next ten years, I believe, you won’t be able to find any native freshwater aquatic life,” a young fish enthusiast, who requested anonymity, told Roar Media. “The native freshwater life is facing an imminent threat because of these monster fish that are smuggled into the country and bred in local waters.”

The 29-year-old enthusiast is the owner of a commercial aquarium. He has also spent the last three years identifying and painstakingly fishing out invasive species from inland waters. In 2020, he identified at least two alligator gars at the Thalangama Lake — Atractosteus spatula is a Native American fish and one of the largest fish from the region, which can grow to a length of 10 feet. After identifying the gars in the Thalangama Lake, he posted videos about it on social media — and this was not received well. “A lot of people didn’t like it when I exposed them. They threatened to beat me up and kill me,” he said.

It should have been impossible to find such a creature at the Thalangama Lake in the middle of Colombo, he said. But such creatures, he added — which fall under the ‘monster fish’ category for local fish enthusiasts — are introduced to water bodies either accidentally or on purpose. “The owner of the alligator gar would have purchased it while it was still a fry. Since these animals grow in length, it must have outgrown its tank, prompting the owner to release it into the lake,” he said.

Restrictions And Threats

The 2020 National Red List of Sri Lanka, which assessed the threat status of the freshwater fish in the country, notes that the introduction of exotic species is a key reason for the decline in endemic species.

The list identifies more than 30 species of exotic fish that have been introduced — intentionally or accidentally — to freshwater habitats in Sri Lanka. The National Red List reads, “While many of these species were introduced to boost inland fisheries, others were accidentally introduced by the aquarium industry. Some of these species have become invasive in many natural and human-made habitats. They can directly impact freshwater fish either by competing with native species for resources or directly feeding on native species.”

Of the 97 species assessed for the National Red List, 61 are endemic to Sri Lanka. Of these, 12 are considered critically endangered, 29 endangered and 10 vulnerable.

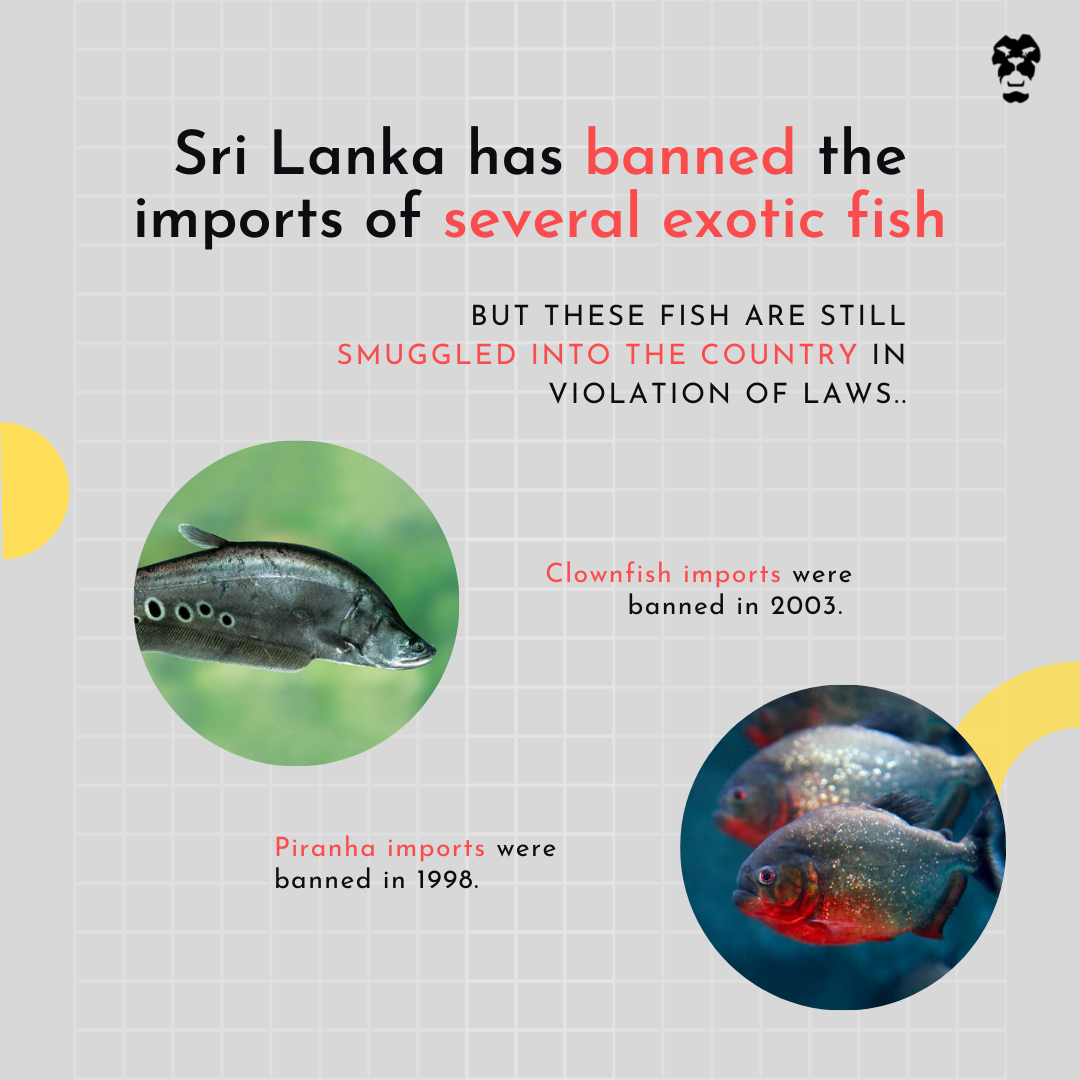

While Sri Lanka restricts the imports of non-indigenous species under the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act and the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinance, some experts claim that due to political influence, the smuggling of animals takes place often. “The Ministry of Fisheries provides permits to import exotic fish using an authority that they do not have,” Samantha Gunasekara said.

“The Ministry [of Fisheries] has the authority to provide permits to import fish that are gazetted under Section 30 of the Fisheries Act. The Act has set out provisions as to which fish can be imported, which fish are restricted and has also highlighted allowed and restricted species for exports. Any exceptions have to be approved by the Department of Wildlife Conservation. But the ministry has continued to provide these ad hoc permits and politically interferes in the process. This is not something that started recently,” he said.

“Smuggling of rare birds, exotic fish, [and] plants such as orchids happen regularly,” Gunasekara said. “When it comes to fish, the smuggling of such creatures under the guise of ornamental fish trade is very present.” This continues, Gunasekara said, despite the ongoing ban on imports that was imposed in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gunasekara is known for setting up the first ever Biodiversity Protection Unit at the Sri Lanka Customs in 1993. He was also instrumental in warning against the importing of knifefish into the country in the late ’90s, when these were accidentally introduced into the natural systems by those in the ornamental fish trade. “When I warned people of the knifefish, they [ornamental fish traders] laughed at me. And it took the government until 2003 to ban the importing of knifefish. But people are still smuggling the species in,” he said.

Gunasekara issued a similar warning regarding the importing of piranhas during the same period, which led to imports of the fish being banned in 1998. However, at present, piranhas are another fad among amateur fish enthusiasts who collect and sell locally. “Some even export them,” Gunasekara said. “This behaviour among our citizens can affect our local ornamental fish trade,” he explained. “There are no reports of these species breeding in natural systems yet. But the possibility of them spreading into local waters is very real.”