The ancient Greek name for Sri Lanka, Taprobane, came from the Sanskrit Tamraparni – Tambapanni in Pali. The Mahawamsa says the term arose because Prince Vijaya’s followers’ “hands were reddened by touching the dust of the red earth”, a play on the meaning “copper coloured hands” – which sounds pretty much like folk etymology.

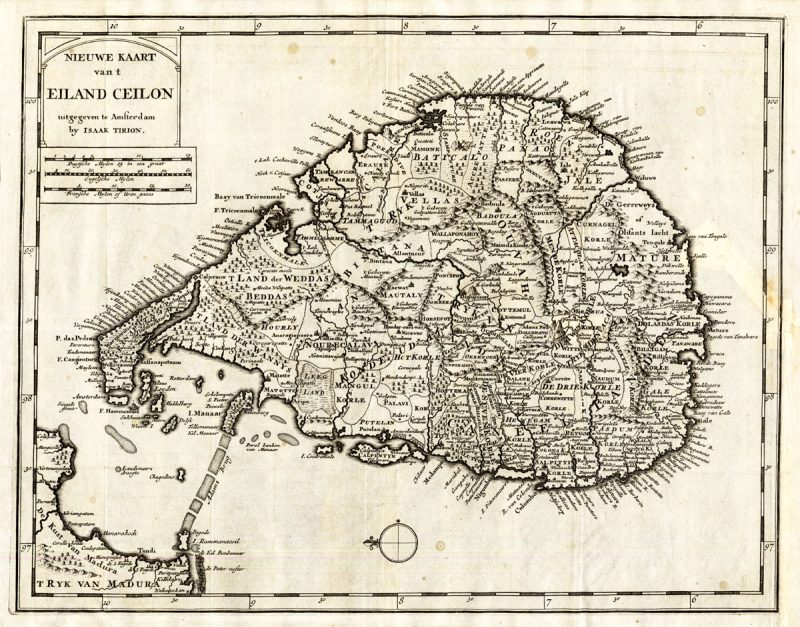

However, Jayasiri Lankage, Chairman of the Cinnamon Training Academy, thinks this is unlikely, and that it actually means “copper-coloured leaves”, referring to the red-tinted cinnamon forests covering the area in early times, from which cinnamon quills were extracted. Maps from the Dutch era mark the forest lands, from Chilaw to Matara, as Caneel Landen (“Cinnamon Lands”).

Old Dutch Map of Ceylon. Note “Caneel Landen”, lower right.

Cinnamon Peelers

We do not know precisely who harvested cinnamon from these forests in antiquity. In South India, says anthropologist Mowshimkka Renganathan, several tribes or castes engaged in collecting wild cinnamon from the forest. Similarly, in Sri Lanka, there may have been several groups gathering cinnamon.

Asiff Hussein, in his Caste in Sri Lanka, states that the Panna (grasscutter) caste of Walallawita Korale peeled cinnamon. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the Dutch brought them down from Sabaragamuwa in the early 17th century. At various times, in different areas, cinnamon peelers can be found among people of the Batgama, Panna, Wahumpura and Yamanno castes

About 1400, the demand for cinnamon peelers appears to have increased, possibly prompted by the expanding market for the spice in the Middle East and Europe following the Black Death. It was at this point that the caste predominantly associated with cinnamon, the Salagama, enters the scene.

Asiff Hussein tells us that, according to tradition, the Salagama, also called Chaliya or Hali, came to Sri Lanka in the 13th century, from Chale in South India, brought hither by Moorish merchants. They came, not to peel cinnamon, but to weave fine cloth.

Weavers

Sri Lankans wove cloth since the earliest times: the Mahawamsa says that the Yakkhini Kuveni was weaving when Prince Vijaya’s followers came upon her. The Periplus of the Erythræan sea, a document dating back to the Roman Empire, says that the country produced muslin (fine cotton cloth “of Sind”). It seems, however, that by the early second millennium, this tradition died out. People of the Berava caste did weave, as they do to this day, but their products were not so delicate.

Chale is probably Chaliyam, just south of Kozhikode in Kerala. The denizens of this area are the Saliyas or Chalias, a caste of weavers who produced calico cloth (named for Kozhikode or “Calicut”), one of the hottest commodities of the 16th-19th centuries. Their traditions are similar to the Salagamas’, including stories of descent from Brahmins and degradation of status by the king (in their case the Zamorin).

The Saliyas claim to have been brought to Kozhikode at the behest of the Zamorin about the same time as the Salagamas’ arrival in Sri Lanka, so there may have been a migration of high-quality weavers southward. They may have originated among the Pattu Sales of Andhra, who wove fine cloth and silks. The caste names Sales, Saliya, Chaliya and Hāli all derive from the Sanskrit Salika, meaning “weaver”.

Sales of Andhra Pradesh, weaving silk. Image courtesy shatika.co.in

Proletarian

During the time of Vijayabahu VI, says folklore, the Salagamas earned the ire of the monarch, who degraded them to cinnamon-peeler status. This probably had to do with a shortage of hands to meet increased demand for the spice. They had to provide quills of cinnamon to the king as their Rajakariya (work levy) ‒ a practice continued by the Portuguese, Dutch, and British colonial powers.

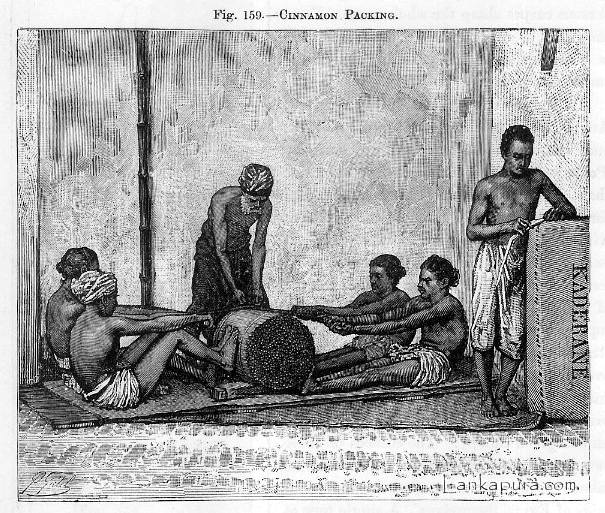

The work is hard, and requires considerable skill, as well as the use of both hands and feet. The tissues of the outer stem must be scraped off the inner stem, the bark must be loosened from the wood by rubbing with a brass rod, and it must be peeled off and rolled into a metre-long quill.

Stereoscope image of women peeling cinnamon. Image courtesy University of Washington

The late Dr. Colvin R. de Silva used to say that the Salagama were “the first proletarian caste in Sri Lanka”. Certainly, they were well organised and would sometimes down tools and decamp into the Kandyan Kingdom, where the Dutch could not reach them. The Dutch were forced to grant concessions to woo the strikers back to work.

Not all Salagamas were cinnamon peelers. There were sub-castes of cinnamon peelers, coolies, messengers, and soldiers. The last two provided, respectively, management and security for cinnamon operations, which could be complicated: drummers were provided to chase away wild animals while harvesting cinnamon from the forests.

The pre-eminence of cinnamon in the commercial world-view of the colonial powers resulted in the caste gaining status, as well as considerable wealth. They also gained the gift of the gab, with witty repartee – Hāli kata (Salagama mouth) in the vernacular. A Sinhala spoonerism popular among the Salagamas is “Pāli hal karanna bæ” (Pali cannot be written using the hal mark – which, in Sinhala expresses an un-vowelled consonant); which converts to “Hāli pal karanna bæ” (Salagamas cannot be humiliated).

Cinnamon Gardens

The eminently practical Dutch of the United East India Company (VOC), the world’s first multi-national corporation, decided to establish cinnamon plantations in Sri Lanka, in order to ensure an adequate supply of the spice through wars and droughts; as well as to prevent workers decamping to the Kandyan Kingdom at the King’s order. However, the canny cinnamon peelers told them it was impossible. In 1769, Governor Iman Willem Falck began experimenting with growing cinnamon from seed at his botanic garden in Grandpass. Swedish botanist Carl Per Thunberg (after whom Thunbergia is named), who visited the garden nine years later, wrote:

“They planted the seeds and these germinated well, but soon the young plants withered and perished. They searched carefully for the cause of this destruction so premature and unexpected: it was discovered that the Sinhalese, who gained considerable profit from barking the wild cinnamon trees, feared that their profits would diminish from its cultivation and its propagation by individuals. Therefore they decided to ruin the Dutch trials and succeeded by pouring hot water over the young stems. The ruse was discovered and they planted many more seeds than the first time. Now plants are cultivated with equal success in Sitavaka… Kalutara and Matara.”The success of Falck’s experiment led to all the native korale (county) headmen being instructed to open cinnamon gardens. Falck’s second cousin, Cornelis de Cock, the Dissawe (or bailiff) of Colombo, ran one of the biggest. Situated in Maradana, it stretched westward to the Beira Lake, southwards to Bambalapitiya, and inland to the borders of Kotte. Maradana means “sandy plain”, and sandy soil meant that cinnamon could mature in five years, instead of seven in good soil.

Temple Trees

When the British took over from the Dutch, says Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, in Ceylon Under the British Occupation, Cinnamon Gardens contained 3,826 acres (1,548 ha), but only a fifth was under cinnamon, nearly half being private fields and gardens. The British re-organised cinnamon production, placing it under a Superintendent of Cinnamon Plantations.

Several extraordinary men filled this post over the years, such as the first, the Frenchman Eudelin de Jonville, who wrote Some Notions about the Island of Ceylon; and Henry Marshall, author of Ceylon: A General Description of the Island and its Inhabitants.

Undoubtedly the most disreputable was John Walbeoff, who was involved in a notorious divorce case. Apparently, while his accusations about his wife’s adultery were true, public sympathy lay with Mrs Walbeoff because of his scandalous goings-on. Walbeoff died in a hunting accident near the Kadirana government cinnamon plantation, in Negombo. With a salary of GBP 1,500 (equivalent to LKR 30 million today) per year, he was wealthy. His house in Colpetty, renamed “Temple Trees” on account of the frangipani trees adorning its gardens, was later bought by the government and is now the official residence of the Prime Minister.

Temple Trees. Note the branch of frangipani at the top left corner. Image courtesy Prime Minister’s Office

Decline

The British lack of experience, Colvin R. de Silva reports, and the unwillingness of the Dutch or the Salagamas to impart it to them, led to them making all manner of mistakes in cinnamon cultivation, and production declined. Their problems were compounded by falling prices. The Dutch had maintained a deliberate shortage of cinnamon, with a view to matching demand, selling only about 180 tonnes a year – even burning the excess harvest. The British exceeded this figure by 50 tonnes annually, and the (now expelled) Dutch released another 80 tonnes of their old stocks every year.

The resultant glut caused prices to fall rapidly, thereafter continuing at the same low level for the next half-century. Competition increased because, in the 1820s, the Dutch smuggled out cinnamon plants (and Salagamas to peel them) to Indonesia, to begin plantations there.The situation worsened because consumers increasingly used cheaper cassia as a substitute for cinnamon.

Finally, in 1833, the government surrendered its monopoly and gradually sold off its cinnamon lands. Collapsing prices put paid to a brief “cinnamo-mania”, and the 1840s Coffee Rush ensured the continued decline of cinnamon. Dethroned by coffee, and later tea, the cinnamon industry only revived in the 20th century.

Packing Cinnamon For Export in 1884. Image courtesy lankapura.com

Cinnamon cultivation died out in Cinnamon Gardens. In 1859, Sir James Emerson Tennent, the former Colonial Secretary, mourned its passing, saying the garden:

“exhibits the effects of a quarter of a century of neglect, and produced a feeling of disappointment and melancholy. The beautiful shrubs which furnish the renowned spice have been allowed to grow wild, and in some places are scarcely visible…”

Residential Land

Cinnamon continued to be cultivated by locals. For example, according to the Ceylon Almanac for 1858, in the Colombo suburbs of Welikada and Nawala, a Burgher, J. B. Misso owned two plantations; a Tamil, A. Pannambelan, one; a Muslim, S. L. Markar, one; and five Sinhalese held the remaining five: C. Dias Modliar, C. J. Fernando, D. J. de Silva, M. Rodrigo and B. de Silva Aratchy.

The erstwhile plantation of S. L. Markar, known then as “Marandan Kurunduwatte” (sandy plain cinnamon garden), is today a residential area. The only reminder of its old name is “Kurunduwatte Mosque Lane”, lying off the Nawala Road near Welikada Junction, next to the Nawala Jumma Mosque.

The government sold its cinnamon lands in Ekala, Kadirana, and Moratuwa to potential cultivators. However, Cinnamon Gardens, Tennent tells us, were a different proposition:

“But so depressing was the prospect, that Marandhan, from its vicinity to the capital, was felt to be more profitable as a speculation for building villas than for cultivating cinnamon. It was disposed of in lots; but not before neglect and decay had so depreciated its value that the price for which it was sold was almost nominal.”

Posh Neighbourhood

Some years ago, this writer heard an anecdote about this from one of the senior engineers in the Sri Lanka Railways. His grandfather, who lived in Bambalapitya, decided to go out. His wife (the senior engineer’s grandmother) asked him, “where are you going?” “I thought I would go to Cinnamon Gardens,” the husband answered, “and buy two acres of land for twenty rupees.” “Don’t you dare waste your money” said his wife. So he had stayed at home.

At that time, the prime residential areas were Mutwal (for Europeans) and Kotahena (for locals), plus Grandpass for “country homes”. However, values rose slowly in Cinnamon Gardens, especially after the Race Course moved there from Galle Face. Clubs and large houses began to come up. The process of gentrification culminated, at the turn of the 20th century, in Royal College – the epitome of an elite public school – moving from the Pettah to the site of the Government Dairy, its current location.Nowadays, “Cinnamon Gardens” connotes a posh neighbourhood, much the same as “Mayfair” in London, “Toorak” in Melbourne or “Lutyens Bungalow Zone” in Delhi. In social terms, it lies distant to the cinnamon plantations of yore; even further from the cinnamon forests which lured foreign merchants and conquerors to these shores.

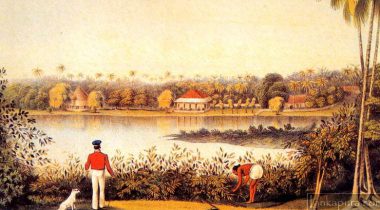

Featured image: “Kolpity from the Cinnamon Gardens”, c.1845. Courtesy lankapura.com