Deforestation and illegal construction in protected areas tend to grab the mainstream media’s attention whenever a popular politician or a public figure is involved in any manner. A good example is, of course, the issue of the illegal construction of a housing scheme inside Wilpattu.

However, there are other cases that go unnoticed by a majority of people, or don’t hold the limelight for long. In recent times, environmentalists have raised awareness about three specific instances of such deforestation and illegal construction in protected or vulnerable areas:

Pallekandal: An Illegal Shrine

Extended structure of the Pallekandal Shrine. Image courtesy EFL

The Environmental Foundation Ltd. (EFL) and the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS) recently acknowledged that a shrine in Wilpattu had expanded into a fully furbished church during the post-war period, at the expense of many trees and protected land.

The St. Anthony’s Shrine at Pallekandal was supposedly built 300 years ago inside what is now known as the Wilpattu National Park. It was originally a small chapel placed in an area of less than a quarter of an acre, and was used in an annual feast for fishing communities who resided around the Puttalam lagoon. They visited the shrine for two nights a year and stayed in temporary shelters until the festival was over. These shelters were then dismantled at the end of the feast.

During the war, this chapel went into disuse, and the building fell into disrepair, with the roof caving in.

In the post-war period, however, not only has the shrine been rebuilt to a greater size than the original, but additional structures have now been added, with clearings being made beyond the original boundaries of the shrine. These are areas previously used by herds of elephants who traditionally graze on the grasslands of the Pomparippu Plain within the National Park, and have done so for thousands of years.

Aerial shot of the Pallenkandel Shrine inside the National Park. Image courtesy EFL.

According to Rukshan Jayewardene, President of the WNPS, the construction and forest clearing undertaken by the St. Anthony’s Church at Pallenkandal, in the recent past, are all within the boundaries of the National Park and are being carried out without complying with the proper law and procedure.

“National Parks are declared because a nation values and intends to protect its fauna and flora that forms an integral part of its natural heritage. National Parks afford the greatest level of statutory protection for wilderness, while also providing for regulated public access. Governments hold these lands in trust for all citizens, and special interest groups cannot be allowed to violate the integrity of such Protected Areas,” he said.

The church now celebrates an annual feast on July 10, bringing in a large number of devotees inside the Wilpattu National Park. According to the WNPS and the EFL, over 30,000 people attended the feast last year alone.

Church’s Response

The WNPS had brought the issue of the construction to the attention of President Maithripala Sirisena, Director General of Wildlife Conservation W. S. K Pathirana, and the Catholic Bishops Conference. Letters to each of these parties were sent on July 7 this year.

Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith, who responded to the complaint on July 27, has said that as per the Ecclesial Law, this matter comes under the purview of the Diocese of Chilaw. According to Cardinal Ranjith, the matter falls under the jurisdiction of Bishop Valence Mendis, the Bishop of Chilaw, as per the code of Canon Law.

On July 10, the day of the feast, Bishop Mendis cites an article in the Roman Catholic Church’s official newsletter The Messenger written by Rev. Fr. Isanka Mihiran.

The article dives into the historic background of the Pallekandal Shrine which is, according to the article, said to be erected by St. Joseph Vaz, apostle of Sri Lanka, on his way to Puttalam during the Dutch occupation.

However, according to the article, when J. R. Jayawardene became the first Executive President of Sri Lanka, on the instructions given by him, the late Bishop Rt. Rev. Dr. Edmond Peiris had agreed to refrain from claiming compensation for the 143 acres of land owned by the church which included the acquired two villages of Pallekandal and Wellamundal on the expectation of an alternative as a grant for the Shrine of St. Anthony.

As the second step, President Jayawardene had directed the Land Settlement Department to provide a land permit of 6 acres and 3 roods for the church premises ensuring the propriety of the land. This land permit is supposedly on record.

According to The Messenger, the annual feast has been celebrated with the support and assistance of the Government. The newsletter also states that the shrine is now in the buffer zone of the National Park.

Despite attempts made to contact him, Bishop Valence Mendis of Chilaw could not be reached for a comment on the matter at the time of publication.

The Diocese of Chilaw has supposedly taken measures to co-operate with government officials to organise the feast and to avoid disturbances in the buffer zone. Several discussions have also been held with the Wanathawilluwa Divisional Secretariat, in preparation for the feast.

Fr. Isanka Mihiran writes:

The Department of Wildlife Conservation is often consulted and nothing is worked out without their consent and consultation in organizing the feast once a year. The Department of Christian affairs supplies the movable toilets for the use of the pilgrims. The devotees are unceasingly advised at the Shrine not to harm the God given environment during their visit to the annual feast at Pallekandal.

They are strongly advised to clean up the environs of the Shrine as they leave. The Parish Priest of Wanathawilluwa sees to the fact that the environment is kept clean and undisturbed.

Garbage and polythene bags strewn around pathways inside the national park. Image courtesy EFL

In spite of these assurances from Church factions, EFL claims that the National Park has been disturbed by the large crowds that visit the shrine. Garbage is seen strewn near pathways, while several acres of forest area has been cleared to create a carpark.

In addition, water tanks, various memorials, and statues of deities are observed within the premises of the shrine, within the National Park.

Ehetuwewa: Forest Clearance

A cleared forest area in Ehetuwewa. Image courtesy EFL

In 2015, EFL commenced an investigation based on a complaint regarding forest clearance that was taking place within the Ehetuwewa Divisional Secretariat in the Kurunegala District.

According to EFL, the forest clearance is, even now, being carried out over 1,000 acres of temple land which has been given to two multinational companies.

The illegal project has also aggravated the human-elephant conflict, as between 200-300 elephants live in the forest and surrounding catchment. In the light of this issue, concerns were raised regarding the possibility of land-clearing leading to water pollution, which will directly affect the small-scale cultivations in the area. Wildlife is also believed to be threatened by the land clearance.

Meanwhile, EFL says that illegal quarrying has also taken place directly adjacent to an archaeological site, where eight of the nine existing artefacts have been completely destroyed.

Wilpattu: An Illegal Road

The illegal cut and constructed road through the national park. Image courtesy EFL

From 1988 to 2003, the Wilpattu National Park was closed to the public, as the area was a battleground between the Sri Lankan security forces and the LTTE.

In the aftermath of the conflict, it was revealed that two roads within the Wilpattu National Park were opened for use. One of the roads follows the coastline leading to the Kudiramalai Point, while the other bisects the park.

The two roads had been used by the armed forces during the war, and now present a threat to the surrounding National Park. Regardless of the construction of such a road being a blatant violation of the law, it also has some serious environmental implications such as causing harm to the flora and fauna and will encourage an increase in poaching and tree-felling within this protected area. Several court cases have been filed by EFL, the WNPS, and other environmental organisations regarding this matter.

The case of the illegal housing scheme, the Pallekandal Shrine, and several other cases are entangled with the issue of this illegal road, allegedly constructed by the military during the war. Unfortunately, all the cases are still stuck in legal battles.

Environmental Litigation In Sri Lanka

The most important legal procedure against deforestation and illegal constructions within national parks is the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (FFPO) which was introduced in 1937.

While the Ordinance has itself gone through several amendments in the past, the provisions have remained vastly unchanged. The Ordinance protects the country’s wildlife, wild parks, sanctuaries, national parks, forests, and other wild habitats.

Deforestation occurs due to several reasons, but mainly due to villagers cutting into the forest for agricultural purposes, or illegal constructions within or on the border of national parks.

If the three instances of deforestation we highlighted here aren’t worrying enough, you might want to take a look at some statistics recorded over a period of time.

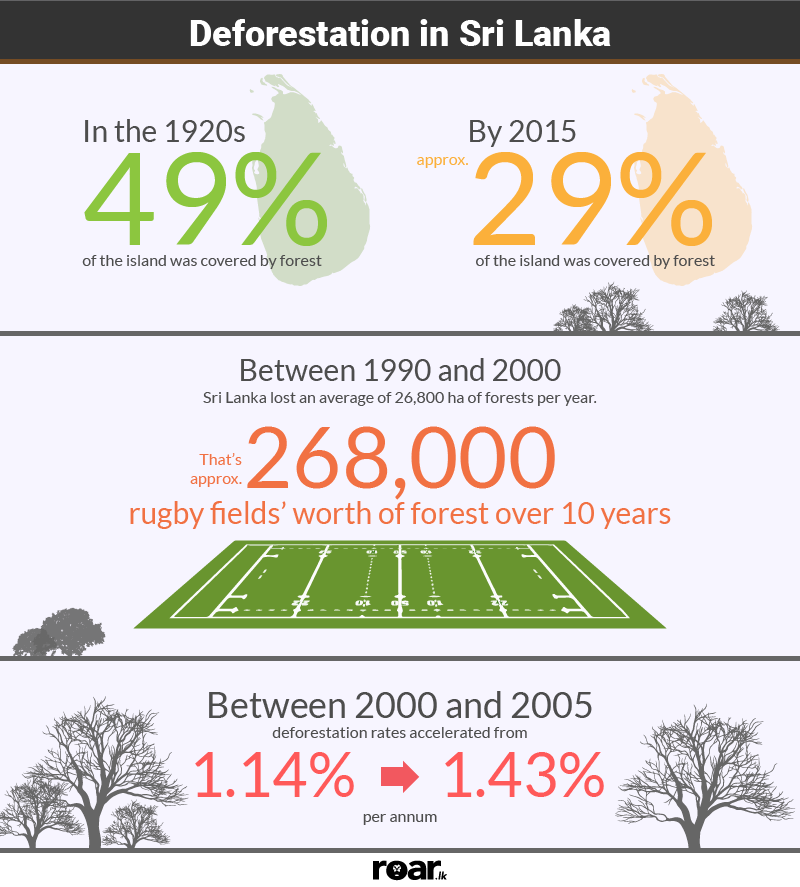

In the 1920s, the island had a 49% forest cover but by 2005 this had fallen to 29.5%. Between 1990 and 2000, Sri Lanka lost an average of 26,800 ha of forests per year. This amounts to an average annual deforestation rate of 1.14%.

Between 2000 and 2005 the rate accelerated to 1.43% per annum. However, with a long history of policy and laws dedicated to environmental protection, deforestation rates of primary cover have actually decreased by 35% since the end of the 1990s.

Sri Lanka’s last forest area survey was conducted in 2011 by the World Bank which shows that forest cover within the country has been on a steady decrease since the early 1990s. Five years later, the situation has not changed.

Like the three incidents we highlighted, there are many that have not received sufficient public or media attention. There may be still others, that have escaped the attention of necessary authorities.

Of the cases that have been highlighted, many remain stagnated within the legal system, taking years to get resolved. The fact that the cases drag on does not only mean justice is delayed, but also reflects a lack of seriousness in attitudes towards the issue at large.

Apart from the fact that another forest area survey is long overdue in Sri Lanka, there is more we could do to address deforestation. For starters, the Government should pay more attention to the issue and prompt more stringent action against those responsible. It is no secret that deforestation is a contributor to global warming, and this is a problem that certainly does not need any more aggravation.

Featured image Brent Stirton / Getty images / WWF