Over the years, plastic pollution has transcended beyond green circles to the public eye because of its visible impacts. Yet, what if the most alarming threats are caused by plastics that are not often visible?

The Invisible Impacts

Everyday face scrubs, shower gels and toothpaste, festooned with tiny plastic particles are readily available at any personal care products aisle. Most of the time products boldly carry labels which say ‘with microbeads’ or ‘containing bursting beads’. To identify whether these beads are made of plastic, it is important to look at the list of ingredients of the product and check for Polyethylene (PE), Polypropylene (PP) or Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

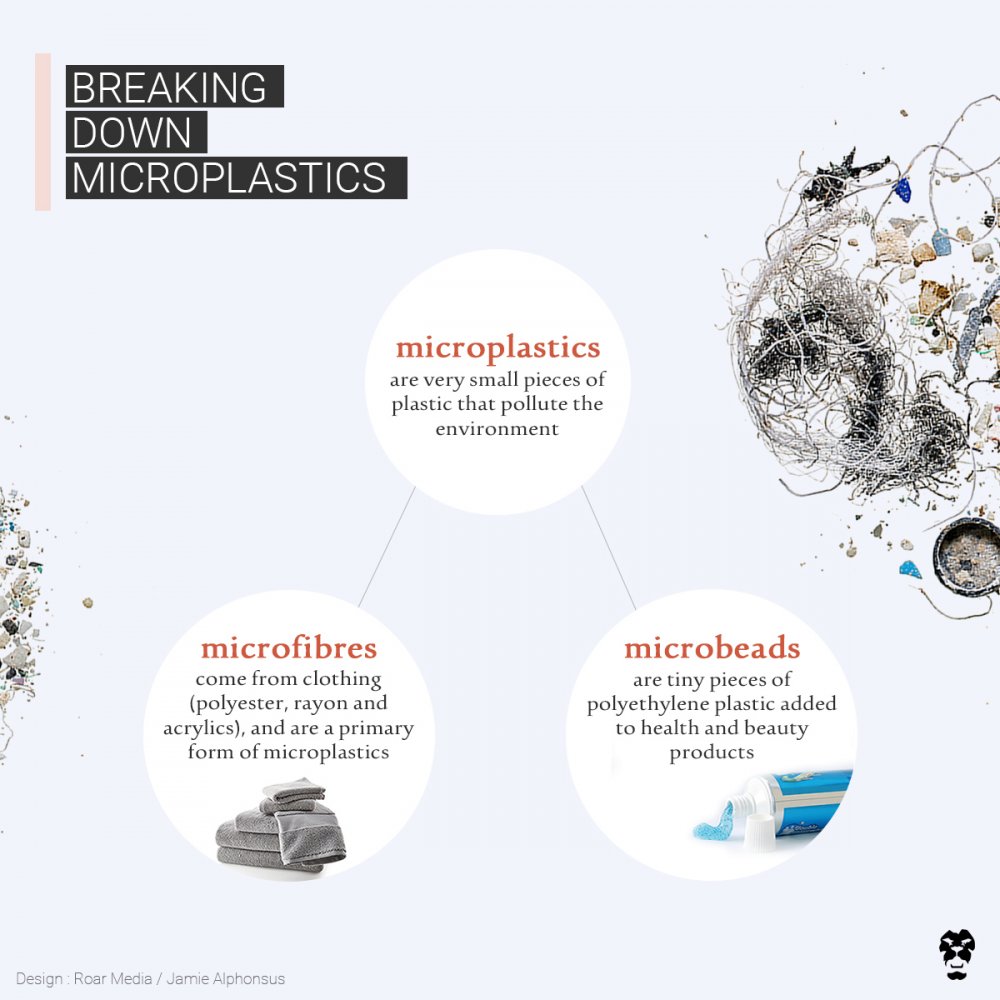

Microbeads, a type of microplastic, first made their way into personal care products about fifty years ago, at a time when plastic was rapidly replacing natural ingredients. Added into the product for the purpose of exfoliation, microbeads are about 5mm or less in size, solid, water-insoluble and non-degradable. Sizes as small as 5mm are designed to be rinsed-off or go down the drain, which results in microbeads easily ending up in waterways where fish mistake them for food.

Once it reaches the ocean, a single microbead can get a million times more toxic than the water around it. Its surface absorbs pollutants that have moved into our seas through land runoff, such as Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), flame retardants, heavy metals, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

Even though plastic is popular for its versatility, what is not so popular are the ingredients added in the manufacturing process that makes plastic so versatile and colourful. Such ingredients consist of fossil fuels contaminants and additives — dyes, bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates and plasticisers.

When marine life such as plankton and sea turtles consume these microbeads, the toxic chemicals can leach out and bioaccumulate or build up in their cells and tissues. The ingestion of microbeads itself could block their digestive tracts, leading to starvation and death. While more than 100,000 marine mammals are killed every year by macroplastic ingestion or entanglement, even particles as small as 5mm could push them further to the brink of extinction as a result of biomagnification- when toxins are passed from one trophic level to the next within the food chain.

Potential Human Health Effects

The omnipresence of toxic microbeads that kill marine species is a canary in the coalmine, reminding us of the need to stop further contributing to the plight. Humans too are no longer immune to the atrocities of microbeads as they make their way right back to the plates of those who consume seafood, validating the classic scenario of “what goes around comes around”.

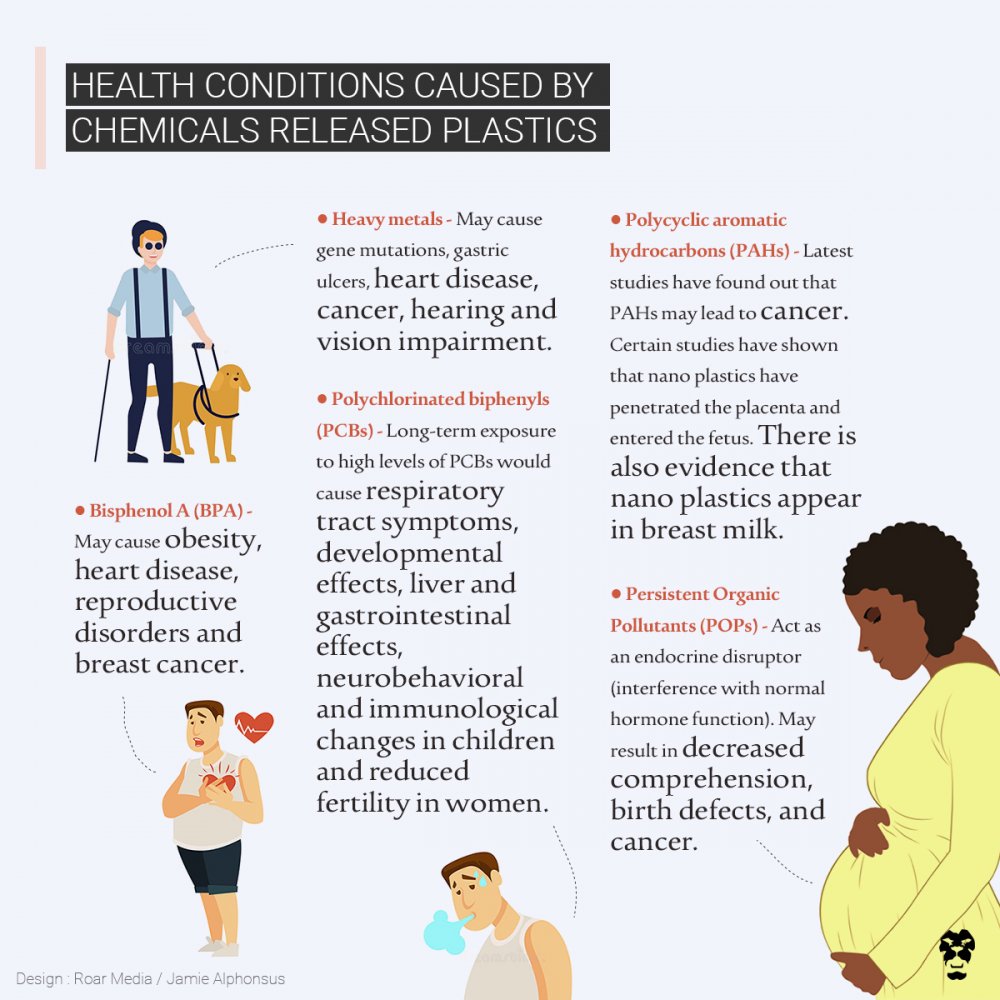

According to Dr. Sajith Edirisinghe, Clinical Geneticist and Lecturer at the Faculty of Medical Sciences in the University of Jayewardenepura, some of the chemicals released from plastics into human organs have the potential to cause the following conditions.

Beyond Microbeads

Microplastics encompass more than just microbeads. As per their origin, they are categorised as primary microplastics and secondary microplastics. Microbeads are primary microplastics that are directly introduced into the environment. Similarly, microfibres that shed from clothing made out of synthetic fabrics such as polyester, rayon and acrylics are considered primary microplastics.

Synthetic fabrics release thousands of microfibers into the environment when machine-washed. Subsequently, microfibres have been detected in chicken, sea salt, honey and even bottled water.

According to the international wildlife charity World Wildlife Fund (WWF), this means that we also consume an average of five grams of plastic, which is the weight of a credit card, every week.

Secondary microplastics are when larger plastic items break down over time into smaller fragments when exposed to ocean waves, wind and the sun’s radiation.

Despite the growing regard for the removal of vast aggregations of large plastic debris that wash up on the coastlines and float on gyres, this visible trash is thought to represent merely 1% of all the marine plastic waste while 99% will stay for centuries in the deepest trenches of our seas.

“The plastic that we see on the beach is much less compared to the plastic in the ocean. We see mountains of plastic waste on the seabed. The nets not only catch fish but plastic as well,” Sarath Suwaris, a fisherman at Dehiwala beach, told Roar.

Likewise, footage captured by The Pearl Protectors, a marine conservation organisation, off the Palagala reef in a video clip titled ‘Plastic Seabeds of Sri Lanka’ reveals this unseen amassing.

The beaches, however, have not been spared by microplastic pollution, which is often buried beneath the sand. A study conducted in Sri Lanka’s southern coastline found that 60% of the sand samples and 70% of the surface water samples collected contained microplastics up to 4.5mm in size.

Accordingly, whilst macroplastic pollution might just be the tip of the iceberg in comparison to microplastic pollution, the need to halt the generation of at least the single-use plastic waste cannot be overstated as they eventually break down into fragments that wreak havoc in the environment. A study suggests that there could already be as many as 51 trillion microplastic littering our seas – that is 500 times more than stars in our galaxy.

The Way Forward

Microplastic litter, to date, cannot be collected or recycled as comprehensively as larger plastic debris. In light of this, it is imperative to provide solutions at the grassroot level for intentionally added microplastics by imposing bans or voluntary phase-out methods.

As opposed to other types of primary microplastics, the shift from microbeads is one that is easy to make since a variety of biodegradable alternatives, namely whole oats, coffee and jojoba beads are effective exfoliants.

Consequently, countries including Canada, UK, Netherland and Taiwan have set out to ban microbeads while some countries have submitted proposals to do so. In countries where bans are yet to be imposed, campaigns such as ‘Beat the Microbead’ have led the way for many cosmetic brands to voluntarily phase out microbeads from their exfoliating products.

Against this global backdrop, Sri Lanka is yet to address the crisis at hand as products adorned with microbeads are still readily available in the market.

“The importation of microbeads can be banned under S.23 W of the National Environment Act since almost all the products containing microbeads in the market are not locally sourced. For adequate implementation, a grace period can be given to sell the stocks that have already been imported and impose the ban thereafter,” said environmental lawyer, Jagath Gunawardana.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), a typical exfoliating shower gel can contain approximately as much plastic in microbeads in the cosmetic formulation as is used to make the plastic packaging it comes in. Nevertheless, due to the lack of widespread awareness on the matter, some may hold the view that microbeads are a smaller contribution to marine debris unlike larger plastics and do not require prompt action. ‘Even so, we must take a proactive approach rather than a reactive approach. Face scrubs and toothpaste can survive without plastic beads that pose an insidious threat,” Mr. Gunawardana emphasised.

“An initiative to ban primary microplastics is crucial. Currently, cosmetics that contain microbeads are being identified to be banned in the near future,” said Dr. Terney Pradeep Kumara, General Manager of the Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA). He added that plans are already in place to ban sachets and several other single-use plastic items by January 2021.

Although the onus of eliminating microbeads cannot entirely be put on the consumer, ultimately the power lies with the consumer to create an ocean-minded shift in demand. Eschewing products that contain microbeads, choosing natural alternatives and engaging in conversation about the problem of plastic at all ages is vital to effectively advocate for microbead-free waters.