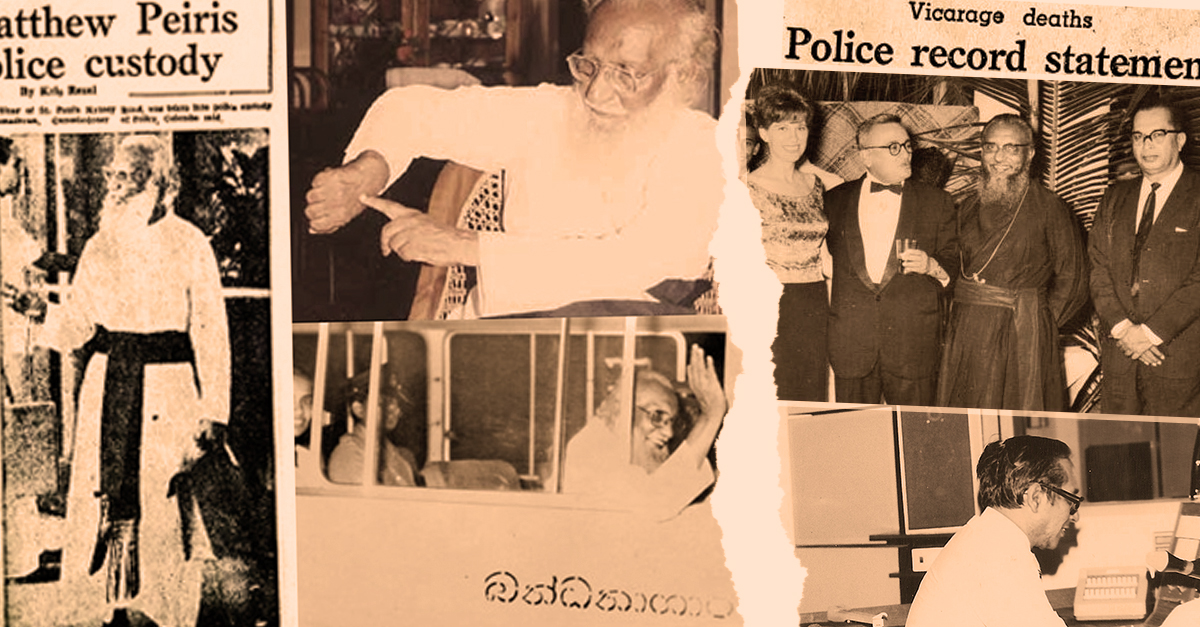

Veteran filmmaker Chandran Rutnam’s highly anticipated film ‘According to Mathew’ finally premiered in November, after almost five years in the making. In the process, it drew the ire of the Archbishop of Colombo, Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith, who disapproved of the clergy being cast in a negative light.

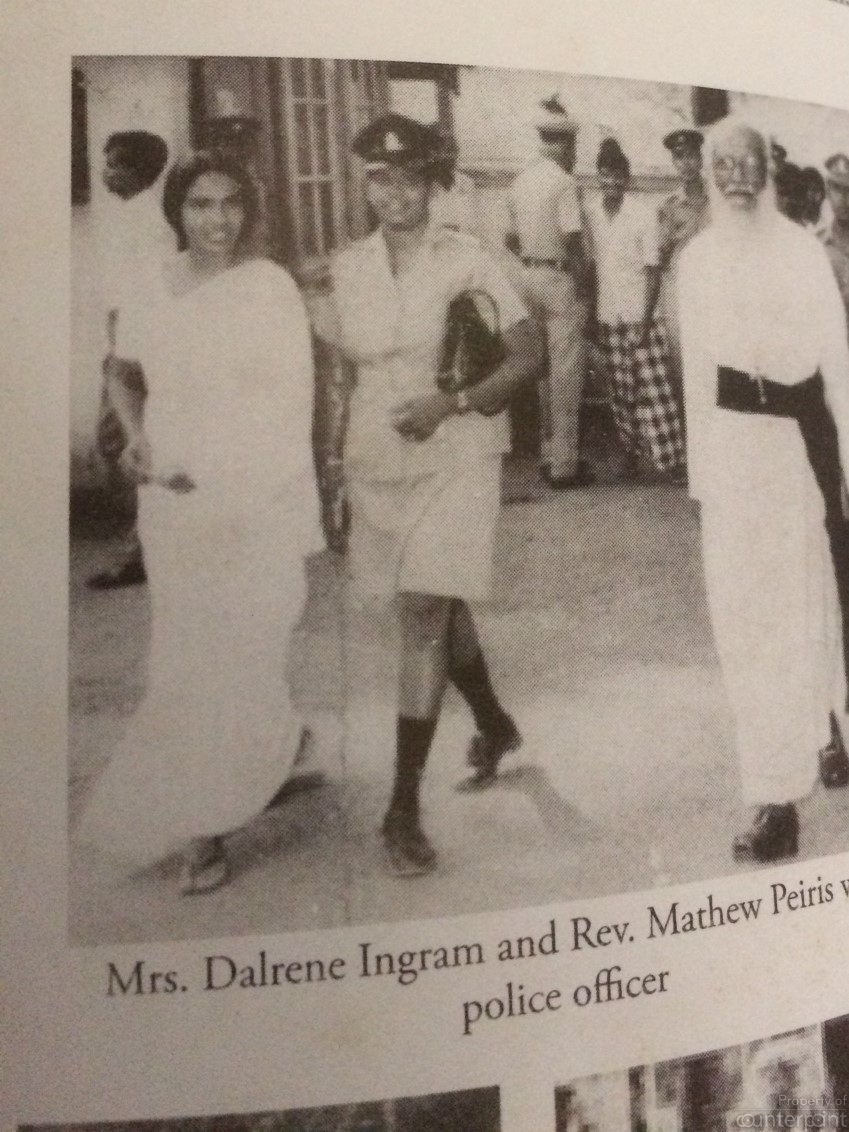

The film tells the sordid tale of the infamous Anglican priest, Father Mathew Peiris, who conducted an affair with his secretary Dalrene Ingram, and was later convicted of murdering his wife and Dalrene Ingram’s husband in 1978/79. The sensational case was dubbed by the press at the time as ‘The Vicarage Murders’.

The People

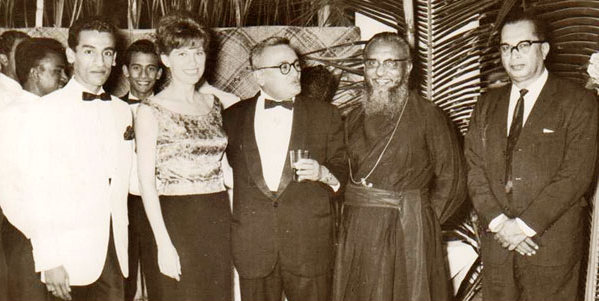

Father Mathew Peiris was a priest belonging to the Anglican Christian Fellowship. Ordained in England in the 1950s, he was the Vicar of Saint Paul’s Church, Colombo. As reported in an interview by Roshan Peiris in 2009, Father Peiris was ordained by no less than the Archbishop of Canterbury, and even attended a summer party at Buckingham Palace at the invitation of King George VI. In his heyday, Father Peiris was a divisive figure, not only due to his charismatic presence, but also because of his his fame as an exorcist who supposedly displayed the signs of a stigmata on his body. His ‘novenas’ drew crowds from far and wide, who came not just to be healed from illnesses, but also for relief from marital problems, family issues, land disputes and other problems. As hotelier Chandra Mohotti recalled in the Sunday Times in 2013, the sheer confidence he exuded made everyone think that Father Mathew was qualified in psychology, when in fact he had no such expertise.

Mohotti recalled how he, like many others, was initially impressed at the successful novenas Peiris conducted. He and several others would look on in wonder as Father Peiris prayed and people fell down during the services. He mentions the priest’srequests for people to meet him not at the church, but instead at the ‘Good Samaritan’s Inn’, a wooden shed behind the church. Mohotti even felt Father Peiris instilled fear in his innocent followers by implying that they would fall victim to serious illnesses such as cancer. When he broke away from Peiris’ influence, he said of the priest: “I have met many confidence-tricksters in my life but never one like Mathew Peiris.”

Filmmaker Chandran Rutnam himself has a personal connection to the case, as Peiris was a close family friend and attended several of the family’s events, such as birthdays, weddings and funerals. As he states here, Rutnam once met Peiris after his incarceration at the Welikada Prison, where the former was shooting the movie, Shadow of the Cobra. Rutnam recollects that Peiris approached him, unchanged in appearance, with a long unkempt beard, a cross hanging from his neck and Bible in hand. The only difference was that instead of a white cassock, he wore jumper shorts like any other prisoner.

The priest had wanted to discuss making a movie about the murders he was convicted of — something that Rutnam was already beginning to work on. During a second meeting, when Rutnam had suggested that celebrated actor Gamini Fonseka play Father Peiris, the priest had protested strongly, insisting that he would be the actor. Even when Rutnam pointed out that he was in prison, Peiris had countered him saying that he would soon be released, in reference to his pending appeal. He also insisted the script depict him as innocent, but when Rutnam resisted, Father Peiris had responded, saying, “I’m like a scorpion. Anyone crossing me, I’ll sting with my tail!”

Rutnam further said that while researching ‘According to Mathew’, allegations had surfaced that Peiris may have been responsible for the death of Father Basil Jayewardene, who served before him at St. Paul’s, because he wanted to take up the position himself. As stated in the law reports regarding Father Peiris’s appeal, Rev. Mathew Peiris v The Attorney-General, Peiris’s wife, Eunice, was about 59 at the time of her death. The couple lived in the vicarage and had two daughters and a son, all of whom were living and working in England.

According to the same report, Russel Ingram and his wife Dalrene were regular visitors to the vicarage from 1976 onwards. The Ingrams attended Father Peiris’s exorcism ceremonies at his church on Thursdays. During this time, both Russel and Dalrene lost employment. They had three young children, as a result of which Peiris employed Dalrene as his secretary and later found employment for Russel at Lake House.

The Events

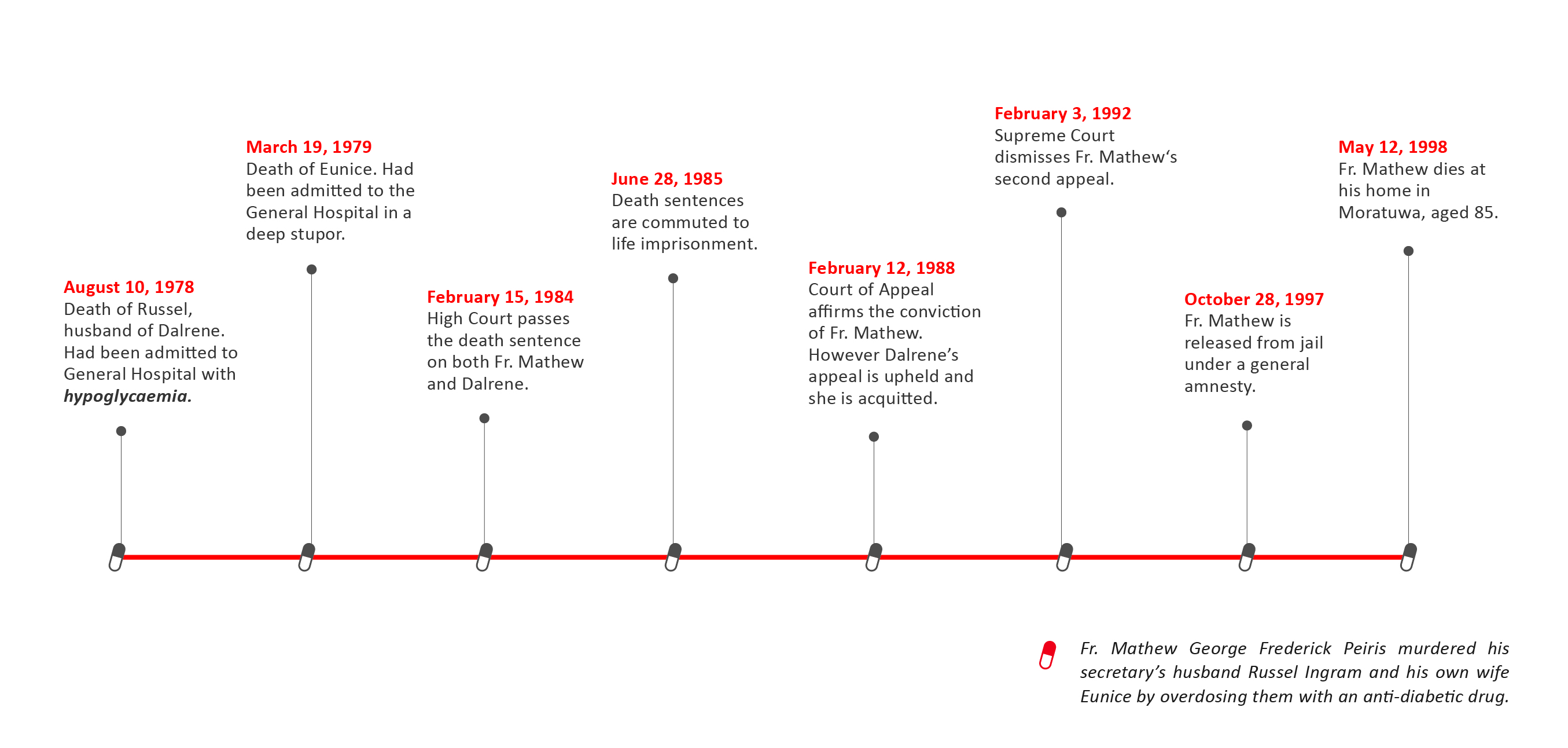

According to the reports regarding Father Peiris’s second appeal, Russel fell ill suddenly on June o6, 1978. He was given some pills by Peiris, who told him that they were prescribed by Dr. Lakshman Weerasena. Subsequently, Russell suffered from drowsiness and bouts of unconsciousness and was admitted to the General Hospital—now the National Hospital of Sri Lanka—but only 20 days later, on June 26. On this initial admission, he recovered soon and was discharged, but was admitted again in an unconscious state on July 18.

At the time, Dr. Mohan de Silva (later Dean and Professor of Surgery of the Sri Jayewardenepura Medical Faculty, and the current chairman of the University Grants Commision) was an intern and witnessed Russel Ingram’s case first hand, as he recalls in an interview with the Sunday Times. The patient, he said, was referred with a letter from retired physician Dr. Ernie Pieris, which mentioned an ‘insulinoma’ or an insulin-producing tumour of the pancreas. This diagnosis was never questioned by the junior doctors since it came from such a senior physician. Dr. Mohan remembers a priest and a ‘timid’ woman accompanying the patient. They were Father Peiris and Dalrene. Dr. Mohan was struck by Peiris’s charisma, especially as he “presented” the case to the doctor in charge, Dr. A. H. Sherifdeen.

Russel was at Ward 18 of the General Hospital for about a month. During this time, Dr. Mohan would see Father Peiris and Dalrene bringing him a liquid diet, which the nurses would add to his nasogastric tube. Peiris would also stop by the doctors’ room and talk to Dr. Mohan. “He had a controlling posture and a hypnotic quality about him. A powerful personality,” recalls Dr. Mohan. After Russell’s death, a post-mortem was performed, but an insulinoma was not discovered. However, since it was possible on rare occasions for an insulinoma to form at sites other than the pancreas, the case was considered closed. It only came to light again when Father Peiris’s wife Eunice was admitted to the General Hospital with very similar symptoms.

Dr. Terrence de Silva, now Registrar of the Sri Lanka Medical Council, was the intern on-call at Ward 47 of the Colombo General Hospital when Eunice was brought in by her husband on January 31, 1979. In an interview with the Sunday Times, he recalled how an unconscious patient was brought in by two priests, one of whom was Father Peiris and the other, a close relative of Eunice. The patient’s medical history was provided by her husband, who told Dr. Terrence that his wife had complained of body pains, thirst and appetite-loss after returning from a trip to England. He also said she had had slurred speech and had been going in and out of consciousness since the day before admission. She was also being treated by a psychiatrist for depression, he said.

“There were certain abnormalities in the fasting blood sugar in those reports,” said Dr. Terrence. Further, Father Peiris had tried to tell him that “glucose was bad” for his wife, and had replied in the negative when asked whether she had been taking anti-diabetic drugs.

Dr. Terrence’s tentative diagnosis was a hypoglycaemic coma due to low blood sugar levels, which he noted down on the patient’s bed-head ticket, followed by ‘pancreatic tumor’, ‘overdose of hypoglycemic agents’ and ‘poisoning’. After prescribing treatment to revive Eunice, Dr. Terrence grew concerned about whether he had administered the correct treatment. He consulted his peers at lunch, who had agreed with him on the given treatment. But it was at that time that a similar case, recently brought in by a priest, was brought up by a colleague.

When Dr. Mohan asked Dr. Terrence why he was unsure, Dr. Terrence replied that “a very authoritative person…..a priest” seemed to disagree with his treatment protocol. Feeling uneasy, Dr Mohan said he surreptitiously visited Ward 47 with Dr. Terrence, to find that it was indeed Father Peiris—whom he had encountered in the previous case of Russel Ingram—who had also brought the second patient in.

From The Law Reports

Subsequently, an investigation was launched and many further details came to light that made it to the law reports for Father Peiris’s appeals: these were the testimonies of Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Dr. P.A. P. Joseph and Dr. E. V. Peiris, who had been consulted about blood sugar. Father Peiris was a diabetic, and therefore knew details about hypoglycemia and blood sugar levels. He also had the book ‘Body, Mind and Sugar’, which gave detailed explanations on hypoglycaemia and the human body’s relationship with sugar. In addition, between 22.09.78 and 11.12.78, he had purchased 80 tablets of euglucon, which is commonly prescribed for hyperglycemia.

According to testimonies from Dalrene Ingram’s sister, Bridget Jackson, and Malrani Peiris, daughter of Father Peiris and Eunice Peiris, the priest had been seen giving pills to both Russel Ingram and Eunice Peiris, and had also withheld information regarding Eunice’s condition from her doctors.

Father Mathew Peiris and Dalrene Ingram were sentenced to death for the two murders. Dalrene was later acquitted on appeal, while Father Peiris’ sentence was commuted to life. However, he only spent the years from 1985 to 1997 in prison, after which he was released for good behaviour. He died in 1998 aged 85, a year after his release from prison.