This last Saturday (January 4) was World Braille Day—so designated by the United Nations in 2019 to raise awareness of the importance of Braille for increasing inclusivity for blind and partially-sighted people. The wide adaptation of Braille has improved the lives of many affected by enabling literacy and equal opportunity. Braille was introduced to Sri Lanka in the early 1900s, but how much has it improved the lives of those using it since then and how much further is there to go? Here’s a quick breakdown of what you need to know about Braille in Sri Lanka.

First, What is Braille?

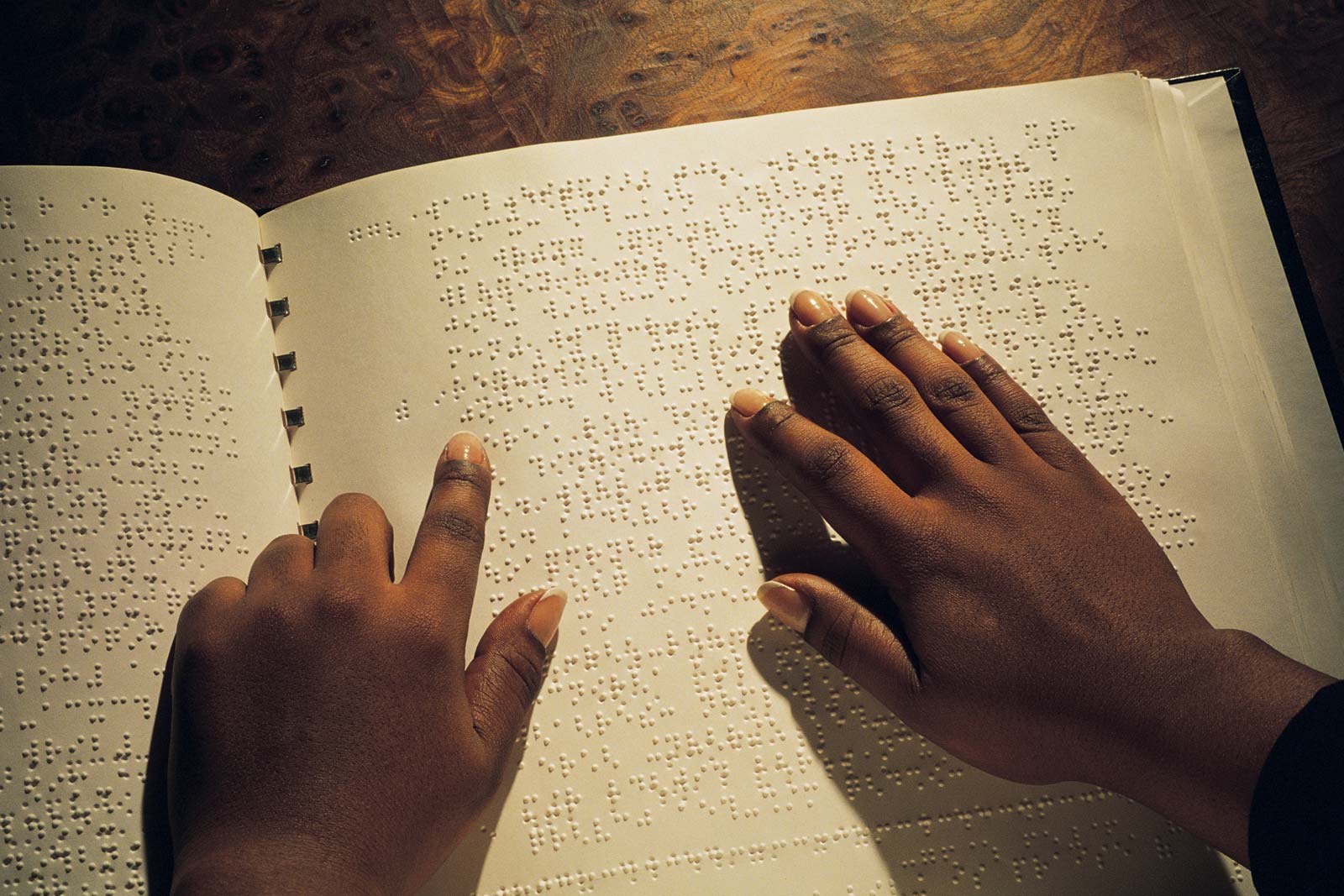

Braille is a tactile representation of alphabetic and numerical symbols using six dots to represent, at the most basic level, each letter of the alphabet and numbers. Braille can also be used to represent musical, mathematical and scientific symbols.

How Does Braille Work?

The characters have rectangular blocks called ‘cells’ or ‘cages’ that have tiny bumps called raised dots. The number and arrangement of these dots distinguish one character from another. All Braille characters are created through the six raised dots in each cage, and each cage is used to denote one particular letter.

Who Created Braille?

Braille was first developed in1829 by a young, blind Frenchman named Louis Braille. He created Braille by modifying a system used for writing at night onboard ships. He found that reading and writing dots was much faster than the previous systems of reading raised print letters, which also could not be written by hand at all.

When Was Braille Introduced to Sri Lanka?

In Sri Lanka, education for the visually impaired was pioneered by the British who established the School for the Deaf and Blind in Ratmalana in 1912, where Braille was introduced to Sri Lanka.

A Catholic school for the deaf and blind was later set up in Ragama in 1935, and in 1956, the Nuffield School for the Deaf and Blind, was opened in Kaithady, Jaffna, to which Tamil speaking students were sent.

During the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, multiple smaller schools were founded by the principals of the Ratmalana deaf and blind school, Rienzi Alagiyawanna and W. Rupasingha Perera, across the country, taking special education to children of rural areas.

Is Braille Available In Sinhalese?

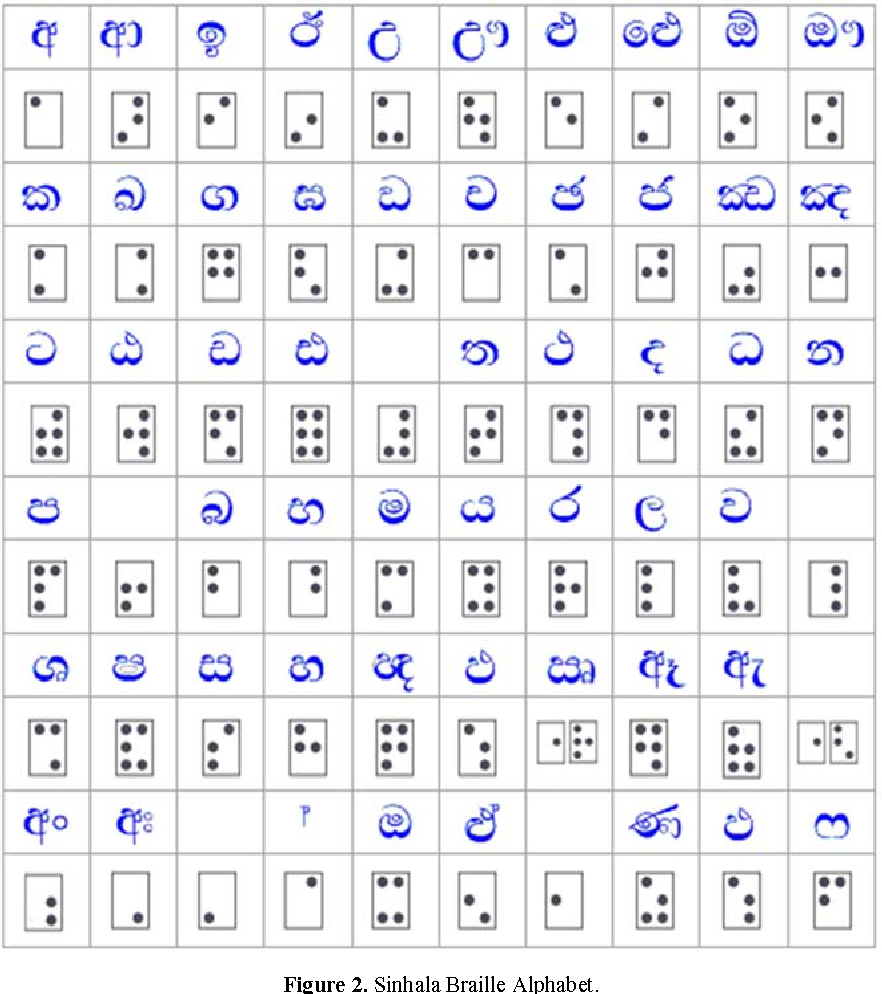

Initially, English characters were used to represent Sinhala letters, however, this system was inelegant and cumbersome. Since the Sinhala alphabet is essentially an ‘abugida’, in which consonants have an inherent vowel that is modified through additional symbols, two English characters were used to represent one Sinhala consonant. And although this method was impractical, it remained in use as there was no alternative at the time.

In 1947, the principal of the Ceylon School for the Deaf and Blind in Ratmalana, Kingsley C. Dassanaike, introduced a more practical code. This version of Sinhala Braille was made to conform to Bharati Braille, a largely unified Braille script that was formulated after India gained independence, for writing the languages of India, most of which are also abugidas.

However, while some languages like English have ‘contracted Braille systems,’ which use abbreviated words in order to save space, such a system has yet to be devised for Sinhala, although several attempts were made in 1959, 1968 and 1997.

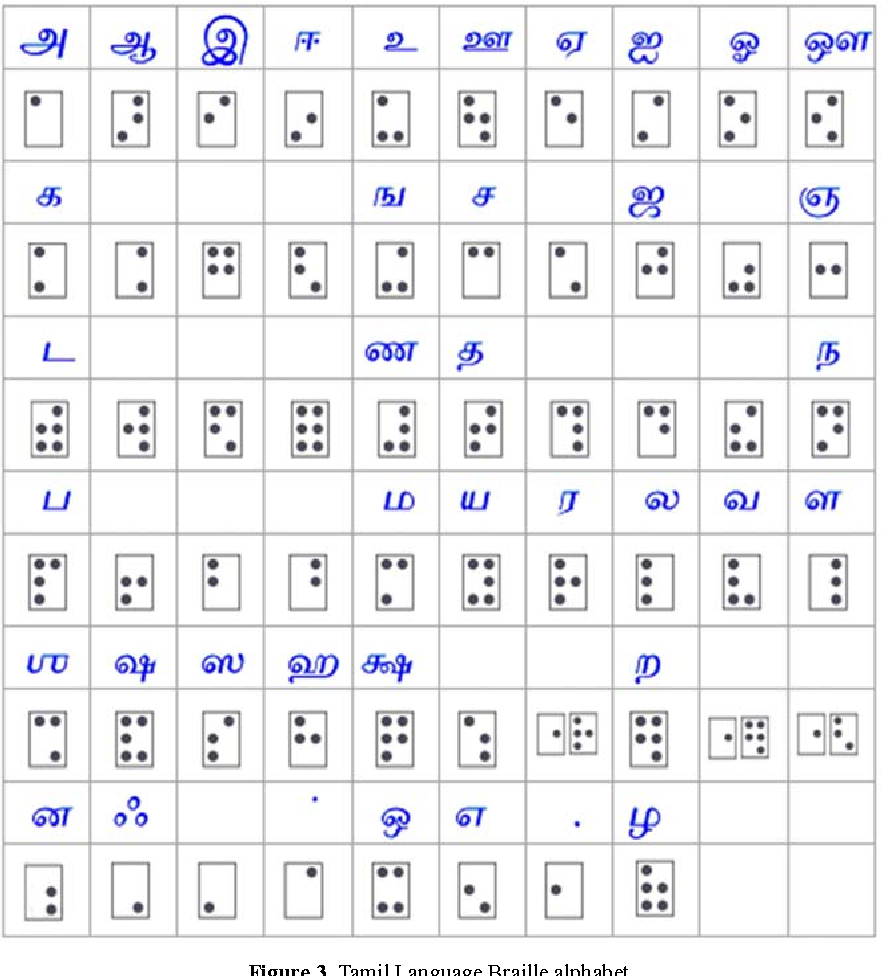

What About In Tamil?

During the latter half of the 19th Century, Braille became the staple medium of reading and writing for the blind around the world. In India, Braille was introduced by missionaries who established numerous schools for the blind. The first Tamil script was devised in 1890 by a “Miss Askwith,” who founded a school for the blind in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu. This script remained in use until 1947, when it was modified, like Sinhala Braille, to conform with the new Bharati Braille alphabet. Based on the Sanskrit alphabet of forty-six letters, instead of the old method which was based on the Roman alphabet, it provided a common script for all Indian languages, with suitable adjustments for each individual language.

The first school in Sri Lanka to teach Tamil Braille was the Nuffield School for the Deaf and Blind, in Kaithady, Jaffna. With only 18 students and 4 staff members at its inception, the school now has approximately 250 students, and is the largest Tamil school for the deaf and blind in Sri Lanka.

How Accessible Is Literature In Braille?

In terms of education, the government of Sri Lanka has provided free textbooks to sighted students since 1980, but the service was not available to blind students until 1985, when a Braille press was established at the National Institute of Education, Maharagama to produce Braille versions of the textbooks prescribed by the Department of Education.

Aside from this, there is still little accessible Braille literature available to the visually impaired, with the only Braille libraries of any size in the country located in big cities, making it necessary for students from remote parts of the country to travel a fair distance in order to borrow or exchange books.

According to the DAISY Lanka Foundation, an organisation working towards improving digital accessibility for the visually impaired, many blind people learn the use of Braille at school, but only 41% of individuals are able to use it later in life. This is due to the lack of Braille writing equipment and reading material in Braille.

Consequently, the visually impaired are often excluded from mainstream vocational training programmes, not just because of employers’ negative perceptions, but also because vocational training materials and instructions are not available in accessible formats.

What Are The Obstacles?

Supun Jayawardena, a researcher at the independent think tank, Verite Research, working to improve disability rights in Sri Lanka told Roar Media there were many obstacles to making reading material available to the visually impaired. “Firstly, [this has] to do with the practicalities of printing Braille,” he said.

Without up-to-date equipment and special paper, Braille book-production is an expensive, time-consuming and labour-intensive process. “Braille letters are larger than sighted letters, and take up more space, so when you need to translate something into Braille, it takes lots of paper, so the document becomes very bulky,” he said.

“Additionally for the dots to be read accurately, you cannot use normal paper, the gauge has to be higher.” Even then, printing Braille books have further obstacles. “Braille letters have more likelihood of damage,” Jayawardena said. “After[reading] a Braille text four or five times, it may become difficult for others to read the same text.”

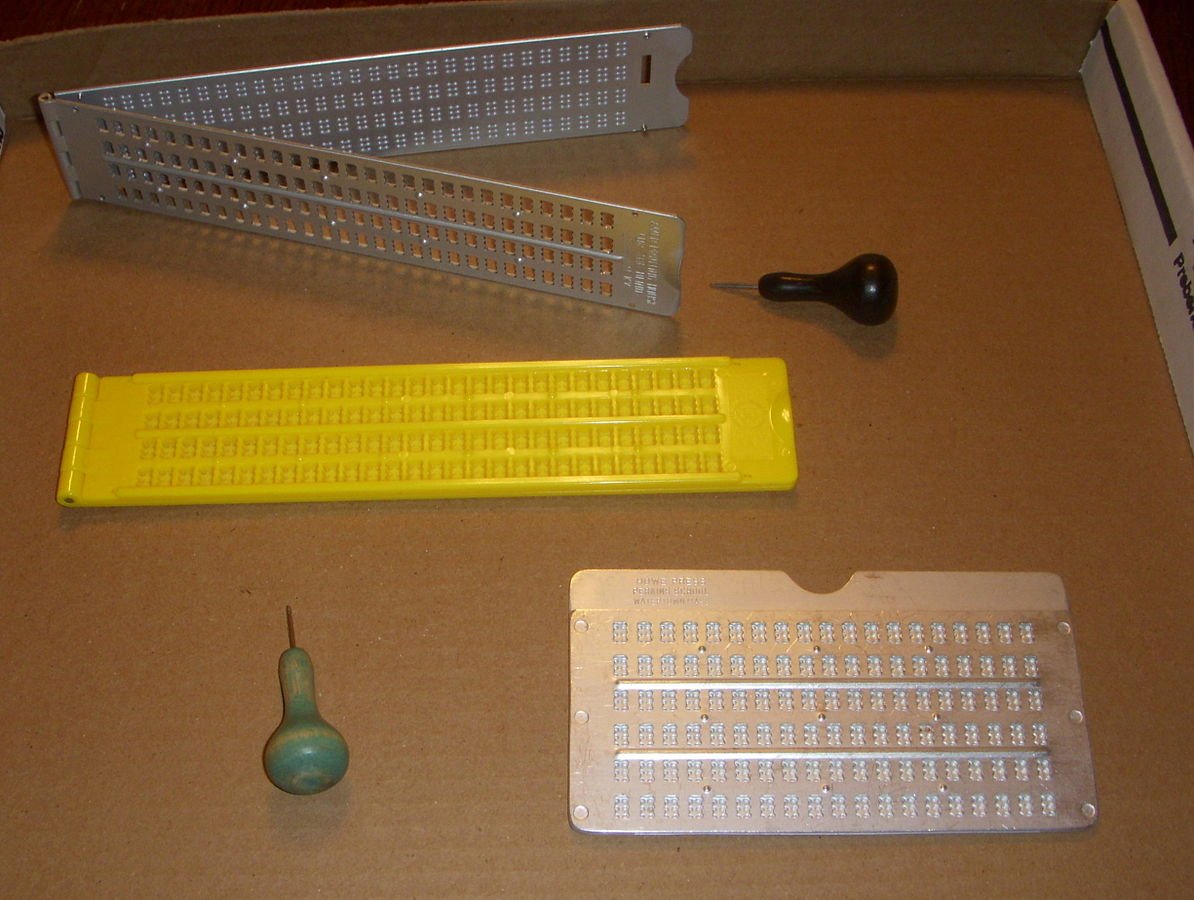

A specialised typesetter which is used to print documents in Braille. Photo Credit: pintrest.com

What More Can Be Done?

Other formats for the visually impaired can be used in different contexts but they each have their problems. “Audiobooks are more expensive because they are time-consuming to make, and with audio, it’s much harder to take notes for instance,” Jayawardena explained.

And while there have been improvements in technology such as Braille touch displays, which uses electronic systems to turn the sighted system into Braille, access to these systems are expensive and remain out of reach for most Sri Lankans.

Jayawardene explained further, that with the improvement of digital ebook reading systems, ebooks had now become a tool, not just for visually impaired people. “[It has become a tool also for what we call ‘print-impaired,” he said. “That is, people who cannot manipulate a book because of some form of disability, including paralysis, cognitive and development conditions, Parkinsons, arthritis…”

The right to access literature for such people is outlined in the Marrakesh VIP Treaty, adopted in 2013, and formally known as the ‘Marrakesh Treaty to Facilitate Access to Published Works by Visually Impaired Persons and Persons with Print Disabilities.’

“It is led by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and asks countries to remove all the intellectual property law and copyright law barriers to creating accessible versions of reading materials,” Jayawardene said. “Sri Lanka has already signed and ratified the treaty, but we are [still] working on creating enabling legislation.”

Moving Forward

Governments are expected to create mechanisms to support and facilitate visual/print-impaired persons and their organisations to create accessible copies of literature for non-profit or for a reasonable cost.

“I am currently a member of a committee to make Sri Lankan laws compliant with the Marrakesh Treaty,” Jayawardene said. “Right now the US has the highest amount of accessible reading material, at just 15%, and in Sri Lanka, it’s much lower, but with the right mechanisms in place, we can work on improving that.”