For Yasodhara Pathanjali (34), a mother of two, being homeschooled happened entirely by accident.

“I remember being able to read, write, and do math when I was three,” she said. “My parents put me through the application process to school at Mahamaya [Kandy]. But then, the week before I was supposed to start, the school painted their outer walls with Disney characters and that was the end of that.”

Believing that the school was lowering its standards by subscribing to Western forms of art and entertainment, her conservative parents found teachers to visit home instead. Having moved to Sri Lanka from the United Kingdom, her family moved back to the UK when Yasodhara was eight, by which time “everyone had sort of forgotten about school.” Once in the UK, Yasodhara’s parents enrolled her in the third grade, where, as an immigrant student who did not speak the language, she was assigned a ‘quick-English instructor’. However, her mother pulled her out of school once again when the instructor’s reports came in. “My mom saw that his spelling and grammar was wrong, and figured she could do a better job,” Yasodhara said.

Yasodhara did eventually enrol in the school system for her Advanced Levels, where she excelled at mathematics. Outgoing and exuberant, she recalls being excited about it.

“When I went in, I was energetic and not burnt out (like most of my classmates). Everything was very new, and I’d go with my arms full of bangles, and really long hair, wearing whatever I wanted,” she said. She had other ‘brown girls’ ask her how she had the confidence to embrace her ethnicity, and realised that she had never had to worry about uniformity and conforming. “And that’s the thing, because I never went to school, I didn’t learn to, or need to conform,” she said. Essentially, being homeschooled helped Yasodhara retain her identity, and be confident about who she was.

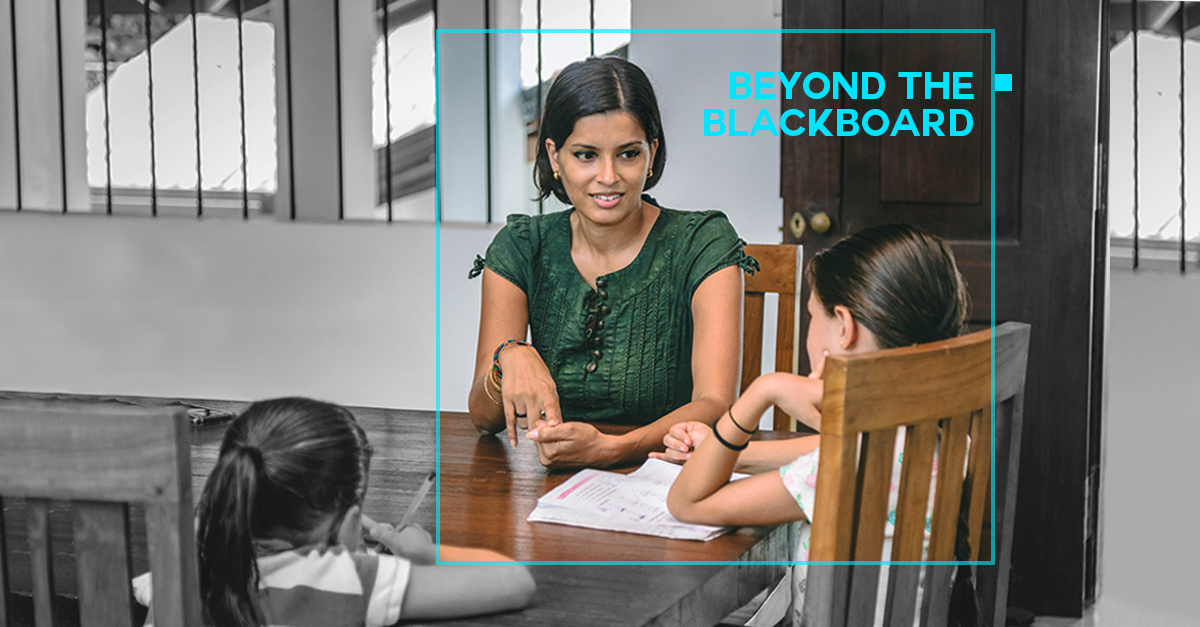

Back in Sri Lanka now, she homeschools her daughters Anuradha (8) and Indumathi (5).

Gaps In The Education Sector

Sri Lanka has 10,194 public schools, most of them following an extremely theoretical national syllabus, and adhering to strict rules concerning dress codes and timing. Teachers in the public sector often find themselves rushing to cover the syllabus, as opposed to focusing on creating an environment that is conducive to learning.

Kavindya Thennakoon, winner of the Queen’s Young Leader Award in 2015 for her work with Without Borders—a social enterprise focused on education—notes the disconnect between schools and the Ministry of Education which governs them.

“One of the things I see is that there is a huge disconnect between teachers and principals, between what the students need, the government, and schools. There’s no connection from the top to the bottom. The Ministry is unaware of the problems schools face, and teachers running things on the ground are disconnected from those at the top,” she said.

Although there are dedicated people working across the sector, this disconnect means that they are working on completely different problems at the same time, Tennekoon pointed out. What Without Borders tries to do is to bridge this gap, by providing case studies of what students actually need, and how the organisation’s pilot projects were successful in meeting these needs, with the intention of integrating these teaching and learning methods into the national curricula.

“We’ve been focusing on critical thinking and problem solving,” Tennekoon said. “Essentially, how we think about things needs to be included in the curriculum. For example, when students learn physics, they need to learn it through a critical lens [as opposed to just memorising a theory],” she added.

Having worked with schools and teachers from Puttalam, Dehiowita, Colombo, and other areas across the country, Tennekoon notes that many teachers are short of time and resources to give students their best.

This is something that Yasodhara feels she can alleviate through homeschooling.

Schools And Identities

“In Sri Lanka, everything to do with your identity is linked to your national identity card and school,” Yasodhara said, referring to how one of the first questions asked in social interactions is often which school one attended. Saying you’re homeschooled in Sri Lanka results in shock, and sometimes, even pity, she said.

For Yasodhara, though, homeschooling has its benefits.

Photo credit: Nazly Ahmed/ Roar Media

“Children don’t have the stress of being at school, and of dealing with traffic. They also have access to a much wider range of educational experiences and can follow their interests,” she said.

Using workbooks published by M.D. Gunasena, her children go through subjects at their own pace, and have a more immersive learning experience while at it. They accompany Yasodhara to meetings, to runs to the bank, and on daily errands. They socialise with people from different spheres and age-groups, and are lively and outgoing.

“Socialisation isn’t socialising with children born in the same year as you, in a classroom, for the whole of your childhood,” Yasodhara said, as her daughters spread their books out on a table, preparing to study. “It’s meeting a variety of people from different settings and learning how to deal with them.”

She pointed out that the concept of education is linear but contended that it shouldn’t be so, explaining that parents had multiple options before them. Of these, she considers homeschooling as a strong option, given that students are allowed to sit for national exams as private candidates.

Her children, who learn at their own pace, often collaborate on homework. The eldest, Anuradha, can read and write, while Indumathi, who is five, cannot. And so, Yasodhara assigns them group work: Anuradha is told to come up with a story, which Indumathi must then illustrate. This way, she combines writing, reading, and creativity in one session.

To also give them the experience of what mainstream education is like, the kids are enrolled at a daham paasala—or Sunday school—to understand what a structured school environment is like.

“While it’s one thing to experience something completely alternative, it’s also important to know where other people come from, and Sunday school provides that,” Yasodhara said. “They have uniforms; you need to ask permission before using the toilet, and there are punishments meted out, just like in regular school. It also gives them a chance to grow up with the same group of kids, so they’d have the experience of ‘childhood friends’,” she added. Currently, the children have friends from very diverse backgrounds and age groups — and have the confidence to converse comfortably with adults, most likely a result of accompanying their parents out during meetings and other duties.

Being homeschooled also releases the family from a rigid weekly schedule: travel becomes possible, and the kids are able to go on more educational field trips, where everything is a learning experience.

“Research shows that education should be delayed until kids are seven. This is something the Sri Lankan government also follows loosely: children aren’t taught to read or write until they’re in grade two. This was something I had in mind for my kids as well,” she said.

However, when her older daughter was three, Yasodhara says she desperately wanted to learn how to read, to know how to ‘understand words’. “I can’t keep her waiting for four more years just because I believed that the age to start reading was seven!” Yasodhara said. So she taught Anuradha the basics of the Sinhala alphabet, and the child picked up reading and writing from there. Similarly, Anuradha also taught herself to speak English—fluently—without having ever used the language at home.

The one disadvantage of being homeschooled in Sri Lanka is that children are not able to enter national sporting competitions, Yasodhara noted, as all young athletes must go through the school system. “If you have an athletically gifted child, they have to go through a school,” she said.

Aside from this issue, Yasodhara, a successful artist in her own right, has no complaints about the experience of teaching her children at home. She feels her children are socialised, athletic, and happy learning at their own pace. They can converse easily with children their own ages, and even with their parents’ friends. Likewise, they have also been taught to be assertive — the kids do not bother with small-talk, and converse with you on their own terms.

During our visit, they chatted about their Sunday school experiences, the friends they made there, and their toys and colouring books, switching between subjects and topics with fluidity. More importantly, they are able to focus on their skills, and not be penalised for trivial issues like braiding their hair the wrong way, or ‘reading too slow’. (One of the punishments meted out to Anuradha for reading ‘too slow’ at the daham paasala, was being made to stand up and read the whole session. It confused her because, ‘How will standing and reading make me read any faster?’).

At a time when the choice of school in Sri Lanka has become synonymous with social status, and where private tuition classes have proliferated with the narrow aim of getting children to excel academically, homeschooling is a learner-friendly—if unconventional—option for children of all ages.

Editor’s note: In light of some questions that have been raised about the legal ramifications of homeschooling, the Education Ordinance issued in 2016 raised the compulsory age of receiving an education from 14 to 16. This is generally thought to mean that school attendance is compulsory up to 16 years of age — unless the child’s parent ‘has otherwise made adequate and suitable provisions for the education of such child’, as stated in the Gazette. Milani Salpitikorala, attorney-at-law and founder of the Child Protection Force, clarified that every child has the right to an education, regardless of where they receive it from. “This doesn’t mean it has to be in a school, as long as the child is educated,” she affirmed.