A weekday morning in Pettah. The incoming Southwest monsoon had brought with it a shower of rain, and dark clouds hanging heavy in the sky portend more to come. The narrow streets are muddy, the dust that usually coats it streets, dampened and turned turbid by rushing feet.

Pettah is usually a fusion of rushing porters, loud vendors and hurried commuters—and today is no different.

But in the mid to late 17th Century, the landscape was.

Pettah, then known as the Dutch Ouad Stad (Old City), was not the busy commercial area it is today, but a residential one, in which Burghers and other communities that served in the Dutch East India Company lived.

Pettah has long since transformed, and very few of the edifices from the Dutch period remain. These include the Dutch Museum, formerly the residence of Governor of Dutch Ceylon, Thomas van Rhee–and this hidden gem, a living anachronism—a building believed to have once been part of the Governor’s Stables.

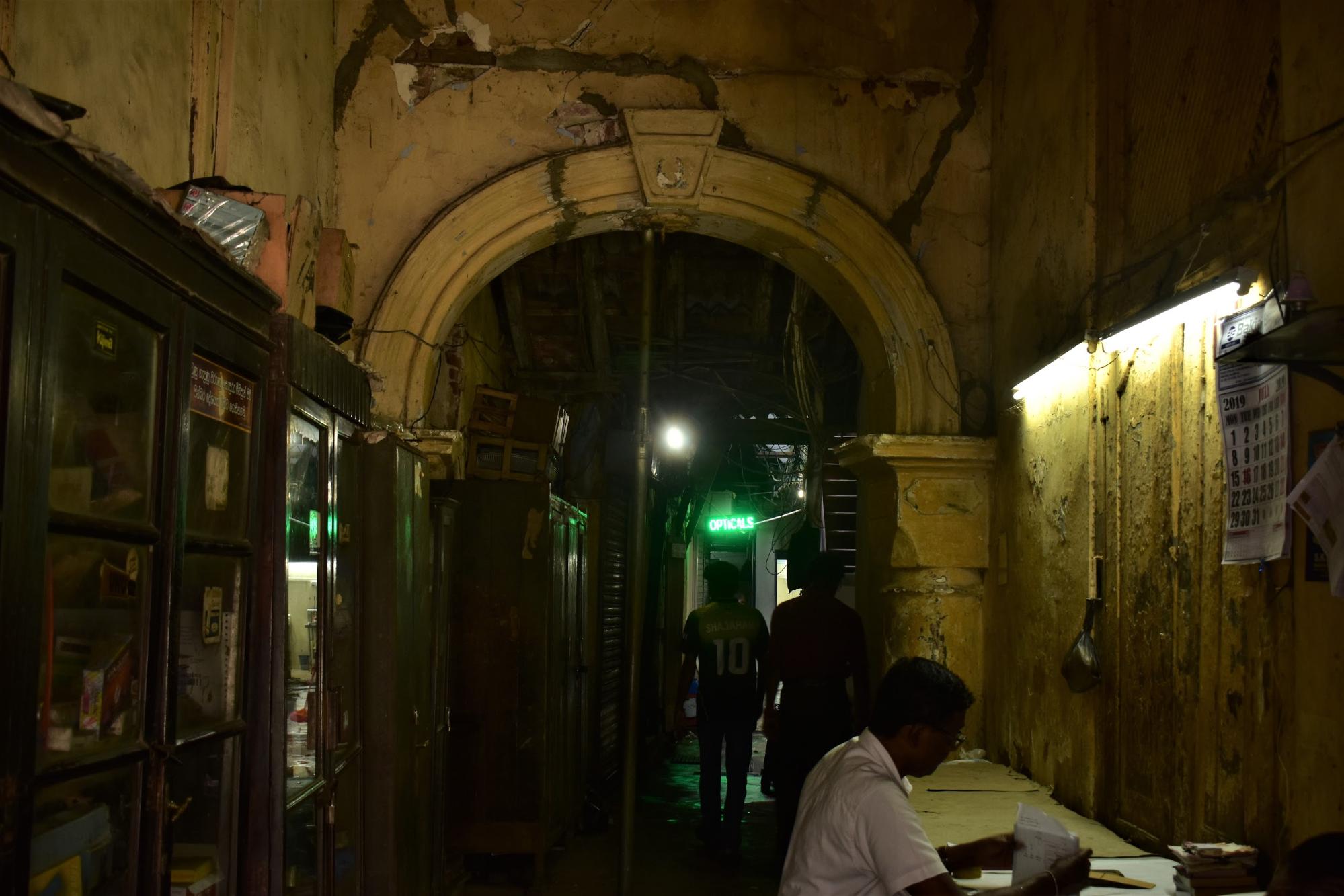

But the entryway belies the history that lies inside.

Upon entering, you find a long corridor lined with old teak glass cabinets, containing various paraphernalia. Photo credits: Roar Media/Kris Thomas

It is here, that Nihal Senarath, Wickramasinghe and ‘Bala’—the three proprietors of the ‘Princely Press’, sit here and chat about this, that and the other.

On either side of the corridor are a multitude of doors that have been walled up.

“This building is over 200 years old, we think,” Wickramasinghe said. “And that horseshoe, right there, means that this was the stables for the Dutch Governor.”

This is contested—archaeologist Chryshane Mendis arguing that there is no proof that the building was the stables of Dutch Governor Thomas van Rhee—in the absence of evidence proving otherwise, the myth is commonly perpetuated and widely accepted.

When I asked Wickramasinghe why he doesn’t repair it, he laughed in my face.

While there is some dispute over the origins of the building—Mendis citing R. L. Brohier, in his Changing Face of Colombo, to point out that many of the residents of the Ouad Stad who owned horses had stables at the back of their homes—also pointing to the fact that the horseshoe was then a common symbol of luck, it is clear that the ‘Old Dutch Stables’, now home to the ‘Princely Press’ is a Colonial building worth preserving.

Pettah has gone through many changes, and will continue to evolve with time. What happens to living anachronisms like the ‘Old Dutch Stables’ now the ‘Princely Press’, remain to be seen.