On 19 April, a private hospital in Pannipitiya, some 16 kilometres south of Colombo, was temporarily shut down after one of its patients tested positive for COVID-19. Sixty-nine staff members including doctors, nurses, and assistants were promptly quarantined.

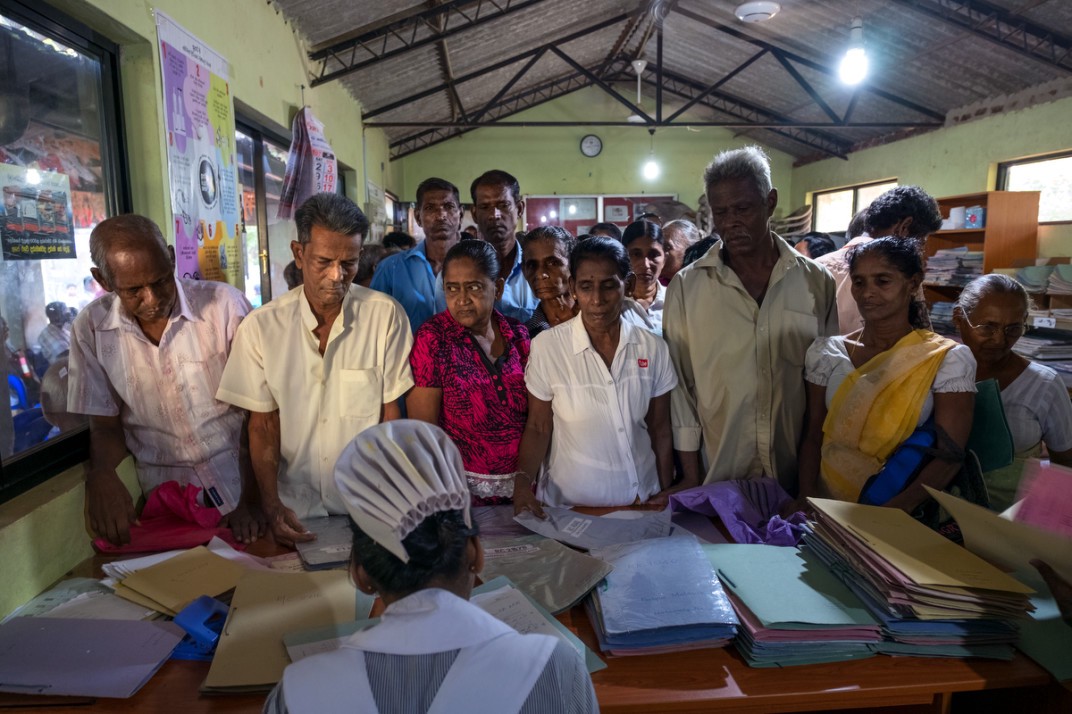

This decision had unintended consequences: a group of kidney disease patients who receive regular dialysis at the hospital were left stranded with no means of hospital care.

“All the other private hospitals refused to take us in. Government hospitals said that they could only accommodate some of us for a short period of time,” Suneth Liyanage, the son of one patient, told Roar.

The curfew and its travel restrictions made it difficult for many with weak immune systems and non-communicable chronic illnesses requiring regular medication or check-ups to seek essential medical attention. The 52-day lockdown only exacerbated their situation.

‘Treatment Refused ’

Asoka—Liyanage’s father—is a 68-year-old retired school principal. He was diagnosed with terminal kidney disease and began his renal replacement therapy or dialysis treatment seven years ago. He must receive treatment twice every week, with a two-day interval between each session. But Asoka was unable to access regular treatment after the private hospital was closed down.

“There are 47 kidney patients who received their dialysis treatment from the hospital that was shut down. And there are over 100 others who would make periodic visits to the hospital for the service. All of them were refused hospital care when they disclosed that they were treated at the Pannipitiya hospital,” Liyanage said.

Kidney patients—especially those suffering from chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology— require continuous dialysis treatment aside from other medication. This makes it almost impossible for these patients and their primary caregivers (mostly their families), to go into home quarantine and deal with the limitations brought about as a result of the curfew.

Even though the government announced guidelines that clearly stated that patients should receive their dialysis as per usual, Asoka Liyanage and the group of other kidney patients known to him were still left vulnerable.

“My father had trouble breathing. He was supposed to have his treatment on 21 April, but couldn’t,” Liyanage told Roar on Thursday (23 April). “We [only] received an appointment at another hospital on 26 April, because that hospital can only accommodate three kidney patients per day. How could I let my father suffer for that long?”

The Immunocompromised

Kalani* (60) is a retired teacher, who was diagnosed with stage three ovarian cancer last October. Since then, she has had to visit the hospital every two weeks for a checkup. However, when variations in blood reports—which can happen quite often as a result of the chemotherapy drugs—are observed, she is asked to see her oncologist immediately.

With the curfew in place, however, she found this a difficult task. This was despite the fact that the Sri Lanka Medical Association issued a set of guidelines for hospitals to manage cancer patients during the curfew, with the objective of allocating limited available resources to all patients during the crisis.

“Since we could not go to the hospital regularly and only when it was a necessity, my mother’s oncologist advised us on what to do at home,” Kalani’s daughter, Janithri* told Roar.

Kalani underwent a scheduled chemotherapy session in the second week of the lockdown. “After a chemotherapy session, she would have had to be vaccinated to control her systems—which she normally receives at the hospital. But we couldn’t do that this time because her oncologist told her not to come to the hospital,” Janithri said.

Matter Of The Heart

Celine De Andrado is 78-years-old and takes medication for diabetes and vertigo while also recovering from pericardial effusion.

“A pericardial effusion is when the area around your heart gets filled up with liquid and compresses the heart,” Celine’s grandson, Mahesh told Roar. “So if you do any strenuous activity it leads to laboured breathing and dizziness because the heart is constricted from pumping blood.”

Since March, De Andrado has been complaining of a swelling in her legs. Her doctor changed her medicine and assured her that there was nothing to worry about. But the medicine she was prescribed worsened her vertigo and she gradually lost her appetite.

“During the height of the lockdown she complained that the swelling had returned, on top of her vertigo. We called Medi-calls and a doctor showed up around an hour later,” De Andrado said.

De Andrado was lucky, with private emergency medical services such as Medi-call being accessible and showing great proficiency. The doctor proceeded to inspect her, speaking to her in a kind, calming tone and prescribed a different dosage to her medicine.

Even when it came to procuring her medicine, she managed to contact their regular pharmacist who had recently set up a delivery system. “All we had to do was send a list of medicines required and attach an image of the prescription if it was required,” he said.

Not all cases were similar, however.

“Since the hospital told us that regular visits would have to be reduced, we had to buy the vaccines and keep it in our fridge,” Janithri said. With curfew in place and unable to travel to hospital as frequently as she needs to, Kalani now receives her vaccines with the help of a retired nurse in the neighbourhood. “She is our neighbour. When she heard about my mother’s condition she agreed to help us.”

In Asoka Liyanage’s case, a solution came after a massive public outcry.

Six days after the shutdown, on 24 April, the private hospital was reopened and Liyanage was among the first to take his father in to receive his dialysis.

Speaking over the phone, he said that he had left his father at the hospital and had come to sleep for a few hours. He had barely slept during the last couple of days. “My father is finally receiving the treatment. He suffered, with us alongside him, for so many days. The other patients have also been given immediate appointments to receive dialysis. I am so glad this is over now,” he said with relief.