Coins are part of our everyday life and they have been for thousands of years. Sri Lanka has seen an influx of a few new coins and lost a few coins as well in the last few years as the rupee has gone on its downward spiral. So, most people have casually held on to some for the sake of nostalgia. But, besides this casual collection, there is also the serious pursuit of coin collecting, where coins that are centuries or millennia old are meticulously preserved and their historical significance recorded. This is called numismatics.

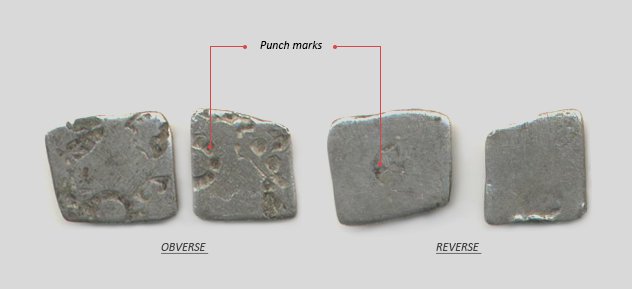

With its robust history, Sri Lanka has rich pickings for numismatists. Coins in Sri Lanka date back to punch-marked coins from 500 BCE, with many more varieties in the centuries since then. Coins are often found from excavations at historical sites or when previously unused government land is opened up for development. For example, many coins and artefacts from the Kingdom of Ruhuna, which was in the south-east of Sri Lanka, were discovered when areas previously protected by the jungle just outside the Yala wildlife sanctuary, were opened up for village cultivation in the early 1980s by then Prime Minister R. Premadasa. Villagers digging the land started finding various ancient artefacts, including coins. Such coins, unless handed over to the government, are usually sold to collectors or various ‘dealers’ who in turn sell them to collectors or museums, with the artefacts often changing hands many times.

For anyone who wants to begin coin collecting, there are numerous books published on the subject. There is also the the Sri Lanka Numismatic Society that began in 1976 for coin collectors in Sri Lanka. Now, they meet on the third Sunday of each month at the Royal Asiatic Society, a part of the Mahaweli Centre in Colombo 7. One of the society’s most illustrious members and foremost numismatists is Dr. Kavan Ratnatunga. We spoke to Dr. Kavan, who enlightened us on the the state of coins as artefacts in the country.

From The Skies To The Past

Despite his extensive knowledge of coins, Dr. Kavan’s initial claim to fame is as an astrophysicist. After studying for his Ph. D at the Australian National University, he joined several other renowned institutes around the world, such as the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton (famed for being the academic home of Albert Einstein, after his immigration to the United States), the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Canada, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, the Space Telescope Science Institute and Johns Hopkins University. In 1992, he joined the Hubble Telescope Project and later researched data from the Hubble telescope at the Carnegie Mellon University, where he made several discoveries.

Dr. Kavan explained that his love of coins, much like his love of astronomy, also began at a young age, when his father and grandfather casually collected and passed down some coins to him. But his own collection only truly began around 1993, when he attended a coin show in Baltimore, at which a seller from Spink, a reputed auction and collectibles company based in London, was offering 11th Century gold coins from Sri Lanka.

Image credits: Nazly Ahmed/Roar Media

“It was the first time that I realised that I could buy one of these and own an 11th Century gold coin from Sri Lanka,” he said. “So, my question to him was, ‘How do I know that it’s authentic?’, because I couldn’t believe that this guy [had this]. He looked at me and said, ‘We are Spink of London, founded in 1666. Why are you asking us that stupid question?’ Anyway, I took his word for it [and] bought the coin. I realise now, with more knowledge after 20 years, that the coin he did sell me was a fake,” he said with a laugh. “I have actually published on my website reasons why I think that particular old coin is a fake.”

Dr. Kavan also said eBay was a big help in growing his collection. As an early user, he had easy access to all the valuable Ceylon coins and memorabilia being sold on the platform. While bidding for coins on eBay now is likely to bankrupt anyone without deep pockets, Dr. Kavan says that in about three years while he was in the United States in the late nineties, he acquired a fairly large collection of Sri Lankan coins.

Subsequent to coming to Sri Lanka in 2005, it took him about three or four years to make the contacts to find coins. According to him, this is difficult to do now. “They are available, but it is difficult to make any contacts now. There are certain dealers who will not sell anything without showing me the coin first [for informal authentication], and therefore I sort of get the first pick at it most often. So that way, I have established a fairly good collection.”

There are also collectors who have sold their collection to Dr. Kavan, trusting him to take proper care of them. “There are certain collectors who have sold their collections to me, [but] wouldn’t sell it to anyone else, because they know I am not going to sell it.” he said. “They felt that they had put in the effort to make a good collection and that I was like the final [keeper] of that collection.”

Failing The Currency

Image credit: Nazly Ahmed/Roar Media

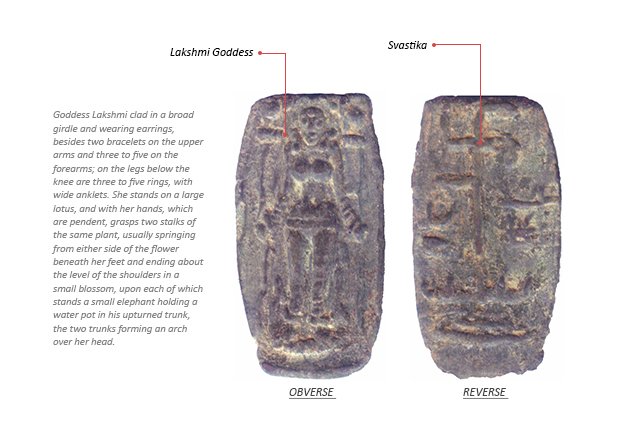

Walking into Dr. Kavan’s home is like walking into a museum gallery, with statues and artefacts at every corner. These include a to-scale Lego replica of a Saturn V rocket and an ancient grinding stone from the Anuradhapura era. A carving of a design from an ancient Elephant and Swatika coin adorns his doorway. Dr. Kavan’s collection spans from 300 BCE to the current era, and it is extensively documented on his website on coins—lakdiva.org—where over 1,000 Sri Lankan coins have been documented.

“The old ones have a very interesting history, dating back to the period of the Buddha or older,” says Dr. Kavan. We were shown coins such as a silver coin from kings Parakramabahu I (1153–1186), Nissankamalla (1187 to 1196) and Chodaganga (1196 to 1197) and Queen Lilawathi ( 1197–1200, 1209–10, and 1211–12). “There is this 1/8th Massa (A type of coin from the Polonnaruwa Era of Sri Lanka) of Dharmashoka. This is extremely rare. An 1/8th Massa of Dharmashoka is something most collectors don’t have. One of them recently sold for Rs. 60,000,” said Dr. Kavan.

“But now I have a problem of how I can protect this [collection] beyond my lifetime,” he continued. “Unfortunately, the places in Sri Lanka are not considered all that safe. There is not really a place where you can trust both the integrity to make sure that this collection will remain safe, as well as the competence to handle the collection in a way that it will not be damaged. Unfortunately, the latter is more real in Sri Lanka.”

Dr. Kavan recounted an incident in which he had wanted to study the collection of 1,048 coins featured in the book ‘Has Ebu Kahapana’ at the Archaeology Department “They said they only had 16 left, and don’t know what happened to the rest. So, I was very disappointed,” he said. “They don’t have proper inventory control in the Archaeology Department, and that’s very sad.”

Dr. Kavan was also contacted by the National Museum to conduct an inventory and produce a report after the robbery at the National Museum in 2012. During this time, he discovered various gaps in the museum’s system.

“One of the things I found was that a collection the National Museum had bought in 1968— and this was 2012—had not been properly documented. [This] is 40 years not documented,” he said. “Because it was not properly documented, I found some fakes in there, but I couldn’t prove that [there were] fakes. I couldn’t prove anything,” he said.

Image credit: Nazly Ahamed/Roar Media

“I will tell you an interesting story which I think is relevant,” Dr. Kavan continued. “There was a collection of fake coins. It was brought to my attention at a coin meeting, where basically somebody showed them, and I said ‘No, these are not genuine’.” After acquiring the coins through a dealer, Dr. Kavan sorted them and looked them up in a catalogue. Published in 1999, the catalogue had drawings of the coins that he was examining. By comparing the drawings, he discovered that the forgers had taken pictures of these drawings and used them to make the coins. Since the drawings were larger than original, they didn’t accurately understand the actual size of the coins. So, they made it larger than the original size, which helped him identify them as fakes.

Having realised these were a cheap set of replicas, he published his findings online, informed everyone in his circles that a collection of fakes was circulating, and that he could prove this without doubt. Two or three weeks later, he received a phone call from the forgers, asking, “Ape kaasi hora kaasi kiyala antharjalaye daala thiyenawada?” (Have you published online that our coins are fakes?) and proceeded to ask Dr. Kavan if he could remove it from the internet?).

Dr. Kavan said with a laugh. “They did something far better. They actually gifted some of those coins to the National Museum, and the ignorant officers in the museum displayed them as lead coins from that era.” And according to him, other than gold coins, they were the only coins that were stolen during the National Museum robbery.

Any Progress?

This kind of administrative incompetence is not the only thing that plagues the preservation of such artefacts. The legal system itself is outdated and unhelpful towards the recovery of artefacts. Dr. Kavan explained that in Sri Lanka, if a coin is found underground, it is technically the property of the state. But it is also required of the state to prove that it was found underground.

“Now if I have a coin, the Archaeology Department can’t come here and say you possess a coin that was dug out of the ground. Because I didn’t dig it out of the ground. Some dealer came and sold it to me. Whether he dug it out or whether his contact or somebody did it, there’s no evidence. So, the only way that this can be monitored, and the government can control it, is if every coin in the country is documented.” He explained that unscrupulous dealers simply melt the coins for the value of the precious metal it is made of, since that is the safest way for them to make money off these artefacts.

“The rules are different in England,” said Dr. Kavan. “Our antiquity laws are taken from [old] British antiquity laws. [In] 1996, or so, the British changed their antiquity laws. They said if any artefact is found in the ground, or wherever, you must report it and produce it to the coroner. The coroner then reports it, and they have an exact location for where they found it, an exact depth for where they found it, and proper documentation. The requirements are that that the coin must be made available to any of the leading museums in England. If they want to buy it at the current market value, they can buy it. If they don’t want to buy it, then the owner can do whatever he wants with it. But in the process, you have information on the place where the coin is found and other documented archaeological information. So this is the problem (with Sri Lanka). The state doesn’t have a means of taking it and by outlawing it, they have encouraged people to melt them,” he said.

“Back in 1988 and ‘98, I think they thought of saying that they would register every single artefact in Sri Lanka,” said Dr. Kavan. “At that time, it was impractical because the computer technology needed to do that is not easy. When I joined the Hubble project, I spent USD 5000 per 2 gigabytes. That was the computing we had, and the storage cost. Nowadays, storage is not that expensive.”

So, it is practical today to collect all this information and store it. However, Dr. Kavan states that before they catalogue private collections, the authorities need to properly document the artefacts in the National Museum and the Archaeology Department, since those are national assets that are not being looked after or documented sufficiently.

“But we have improved,” Dr. Kavan continued. He mentioned several currency and coin museums set up by the Central Bank, the National Savings Bank, the People’s Bank and the Bank of Ceylon too. “But all these places have not properly [handled the coins]. There are mistakes, even in the National Museum collection,” he said.