Being gay in Sri Lanka is still illegal.

However, on Wednesday, November 15, 2017, the government committed to the protection of the LGBTIQ community’s human rights. Deputy Solicitor General Nerin Pulle said, “Sri Lanka remains committed to law reform and guaranteeing non-discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity.”

Despite the cabinet refusing to decriminalise homosexuality earlier this year, this welcome step forward has been commended by the LGBTIQ community, who—according to the law at least—will be entitled to all the same human rights as non-LGBTIQ persons.

That said, this year alone there have been various hate-filled speeches made by religious leaders and powerful politicians. Justice Minister Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe described homosexuality as a mental illness—a stand that clearly influences, and reflects, a society that shares very different views on the freedom of sexual orientation accepted in many nations.

How does one ‘come out’?

Coming out may be considered an intrinsic part of being gay or lesbian, but some view it as a detail. Writer and blogger Brandon Ingram told Roar Media that he had always viewed ‘coming out’ as an unnecessary rite of passage for gay people. “[After all] straight people don’t have conversations with their families and friends about their sexuality”.

Ingram added that “I had to come out to my family twice [first when he was 29 and then again when he was 31], because for the first few years they chose to believe I was joking.”

Colombo Pride has been celebrated each year since 2005. Image courtesy of Foreign Office Blog – Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Sometimes, it appears, actions speak louder than words.

Umanga Samarasinghe, co-founder, and artist at KINGS Co., didn’t suffer any drama at home. To come out as a lesbian, Samarasinghe said, “I took my mum to [Colombo] Pride and gave her tons of leaflets… She got the message!”

For Hash Bandara, Samarasinghe’s partner and co-founder at KINGS Co., college graduation was the moment she came out to her mother. Hash refused to wear a sari but her mother did not like her wearing a tuxedo. A row ensued: “I left home with just a bag of clothes and crashed with friends. I went to go and figure out my life,” she told Roar Media.

In each case, the interviewees said they had reconciled any differences with their parents and families. Now, Samarasinghe and Bandara live together at Bandara’s family home.

Escaping marriage

For many LGBT individuals, coming out is not so straightforward, especially for those of lower economic-standing and/or those who live away from the more cosmopolitan centre of Colombo.

“When I left Ratnapura, my parents didn’t know I was a gay man,” journalist and project officer at Equal Ground, Manoj Thushara, told Roar Media.

“I moved to Colombo for study and was in a long-term relationship with my partner for six years. In this time, our families were putting a lot of pressure on us, independently, to come home and get married [to women locally]. We fled together to Malaysia and received study scholarships, but we eventually returned to Colombo in secret. When our families found out we had returned, they realised the seriousness of our commitment and had to accept us. They had to because, in their eyes, I am the breadwinner of the family. It would be too damaging, financially, to disown me”.

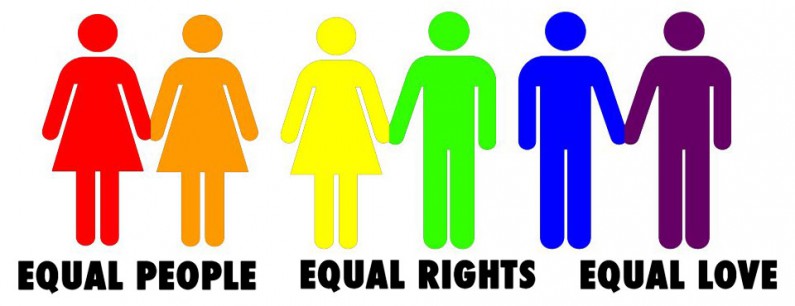

Sri Lanka still does recognise equal rights for members of the LGBTIQ community. Image courtesy YOUniveristyTV

Equal Ground—one of Sri Lanka’s most prominent LGBTIQ NGOs—research and publication “Struggling Against Homophobic Violence & Hate Crimes” (2015), points out suicide, self-harm, and domestic violence in the numerous examples of women being forced into marriages. Besides the social stigma of being homosexual, in many of the cases, women are bound to marriage because there is no alternative, economically.

For instance, the case study of “Sumanawathi” (not her real name) in Nuwara Eliya district, describes how her elder brother demanded that she agree to marriage with someone of his choosing:

“She was threatened by the brother that if she refuses… the proposal… he would take back all the property in his name. [He] insisted that she could not live alone… [and] then started ill-treating her and insulting her. Her brother used to scold her in filth every day. Finally… she decided to agree to the marriage proposal.”

As a result of groundbreaking research such as this, Equal Ground is offering high-value employment and study scholarships to bi-sexual and lesbian women so they can make independent choices in their life.

How does ‘being out’ affect your human rights?

According to a 2016 report in Sri Lanka by Human Rights Watch, “LGBT people, in general, may face stigma and discrimination in housing, employment, and healthcare, in both the public and private sectors.”

Like so much in Sri Lanka, the level of stigma and discrimination an individual is subjected to depends on their social class. Furthermore, the actual stigma people experience can be quite different from what might be expected.

For example, Samarasinghe and Bandara are currently experiencing a unique challenge in finding a place to rent together. Samarasinghe explained, “Landlords are skeptical of two females living together as they presume we are going to have lots of men stay!”

They are not being discriminated against because they are in a same-sex relationship, per se, as it is so far removed from the landlord’s worldview. Instead, it seems, the discrimination starts in the first instance because they are two women. Women, who according to society’s rules, should be married and, therefore, socially and financially bound to a man.

Hash Bandara [left] and Umanga Samarasinghe [right] appeared on the first issue of Equality magazine. Image courtesy Sri Lanka Mirror

The discrimination Bandara and Samarasinghe encounter in hospitals, again, is not necessarily a direct attack on their homosexuality: they are not turned away by medical practitioners or treated unfairly. Rather, it is the structural violence in place that inhibits their right to health care.

“When ‘Manga [Samarasinghe] was admitted to the hospital, I could not sign as her next of kin because our relationship is not recognised by law,” explained Bandara. “It meant we had to call her parents and they had to come to the hospital… It wasn’t a big issue for us as our parents are cool with us, but for many [LGBT] people, this could have opened up some big issues.”

Preaching to the converted

Conversion therapy and curative treatments for homosexuality may well disregard the World Health Organisation’s view that homosexuality is not an illness, but they still thrive throughout Sri Lanka.

Lakmali Kothalawla, Project Officer at Equal Ground, told Roar Media that Ayurvedic and western ‘treatments’ are openly advertised in the local media (newspaper and television). “For Rs 3,000 a session”, Kothalawla explained, “a parent can put a child through intense counseling, or even opt for electric shock therapy.”

Bandara and Samarasinghe had experienced similar scenarios:

“One of our closest friends was dating a girl for seven years. Her parents didn’t like it, so the girls moved out. The parents took the daughter back home and gave her the treatment. We don’t know what happened to her. She’s not allowed to talk to us. All we know is that she’s now dating a guy.”

Playwright and director Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke speaks up for the LGBT community. Image courtesy YouTube

Lower-income individuals in the LGBTIQ community

Due to the extreme prejudice the LGBTIQ community receives, especially those in lower-income communities living away from the cosmopolitan centre of Colombo, the reality of their situation is much more untenable.

Colombo playwright, Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke, spoke to Roar Media:

“I cannot begin to imagine what it is like for the majority of my brothers and sisters in the LGBTIQ community; those whose obstacles are not just emotional, but quite literal. When faced with the threat of being ostracized, violence and even death, I wonder if I could be brave enough to live honestly and openly. I’d hope that I’d have the courage to do so, but I would probably shrink under that kind of pressure.”

That is why it is vital that LGBTIQ groups such as Equal Ground continue their work and have the freedom to work, publish and exercise their right to support people.

Sriyal Nilanka, Media & Communications Officer at Equal Ground told Roar Media that “despite regular blackmail and death threats from extreme religious groups, we are seeing a little progress [politically] as we are now getting invited to government and ministerial events.”

Cover Photo courtesy Equal Ground.