While the striking form of the Nelum Pokuna and the spindly Lotus Tower may dominate the current skyline of Colombo, these grand projects alone don’t define the country’s building style. It is also influenced by how ordinary people build their homes. In these everyday cases, the style isn’t always determined by a trained architect making an aesthetic statement. Instead, factors like building materials, climate, daily routines and local traditions all play a part in the design of a building.

Here are four broad architectural styles that you will be able to see when travelling around Sri Lanka:

Rural Traditional

While temples and palaces stand out of the landscape, the traditional houses of the countryside were built to blend in with the background. Houses are constructed using the wattle and daub (or warichchi) method, where a timber frame is used to support clay walls, which are smoothed with coarse sand, cow dung and water. With thatched roofs made of coconut leaves, these homes were used primarily as cool, sheltered spaces for sleeping and storing tools and possessions. Consisting of only one enclosed space, with little furniture apart from sleeping mats, most activities of daily life would take place outside. Today, rural houses are more often made from brick and concrete with tiled or metal roofs. Although they usually consist of only one or two rooms, their traditional form is still visible.

According to architect Channa Daswatte, in the simplicity of traditional housing, we see a defining feature of Sri Lankan architecture: openness, and the blending of outside and inside spaces. “The pavilion is the quintessential Sri Lankan building,” he told Roar Media. “The salubrious climate only required that a dwelling function as an umbrella, protecting its occupants from the sun and rain, while allowing air to enter.” The pavilion design was used in multiple contexts: as rest stops along roads, meeting halls in villages, and for ceremonial audiences with kings in ancient times.

British Colonial

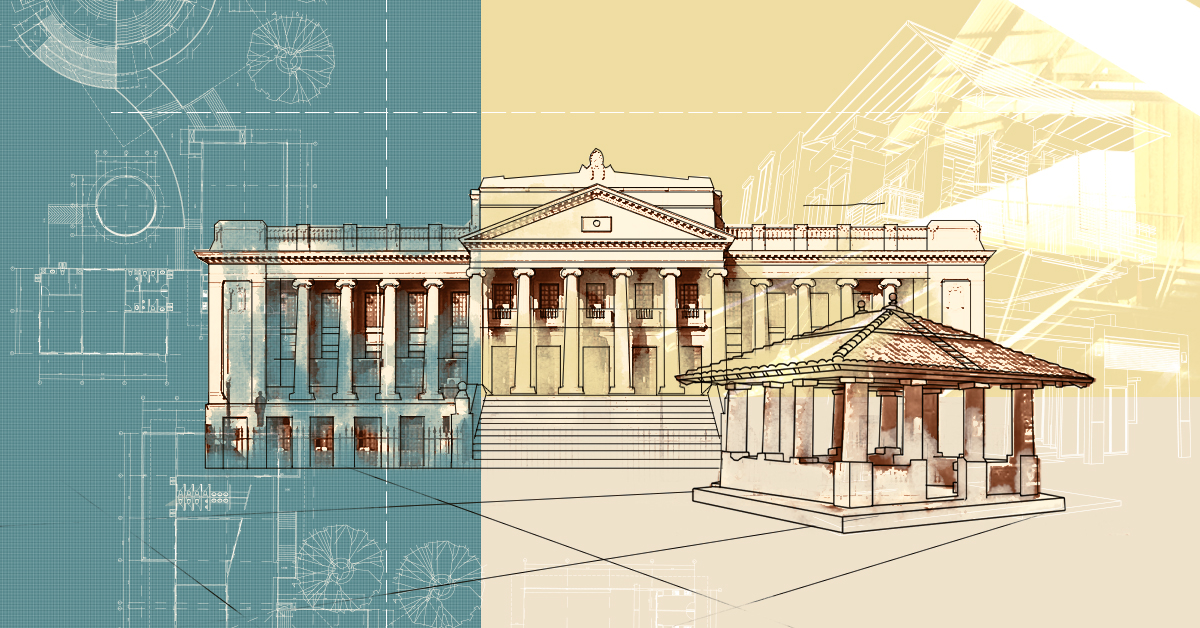

The architecture of the British in Sri Lanka took on two forms. The first can be seen in many of the surviving public institutions, such as the Old Parliament Building, or the Mount Lavinia Hotel. These often conformed to formal European styles such as Neoclassicism, which incorporated elements like symmetrical facades and detailed reliefs. However, some of these structures, such as the Jaffna Public Library, included aesthetic elements from the architecture of local cultures.

Apart from the mansions of the most wealthy British administrators, this mixed style, known as Eclecticism, was not widely used for domestic architecture. For family homes, the bungalow became the basic form. They incorporated functional elements of local architecture, while still following European forms, planning and methods.

A prominent element of British colonial architecture was the verandah. Inspired by the pavilion, the verandah is a porch surrounding the house where the roof overhangs, again creating a space that is both inside and outside. Although it integrated with the native climate and culture, Daswatte explained that the verandah also had a more prejudiced purpose: it allowed the colonialists to meet with the locals, without having to invite them into the house. Similarly, the room arrangement of a bungalow divided its space between the British residents in the front, and the Asian ‘servants’ in the back.

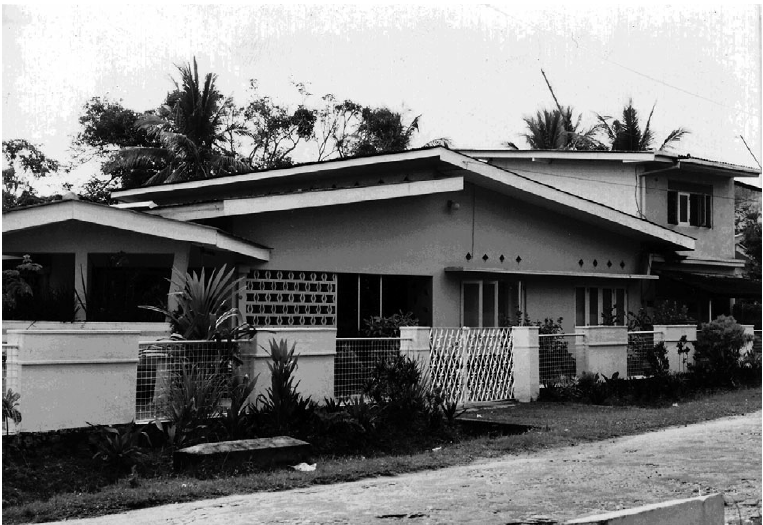

In the early 20th Century, bungalow form and construction was standardised as increasing numbers of British administrators settled in Sri Lanka with their families. The ‘Modern Eastern Bungalow’, as it was known, became commonplace in Colombo and in plantations around the country, and most surviving bungalows follow this style. Based on simple, standardised designs, and using new construction methods, many of the detailed Victorian decorations were toned down. During this time, the bungalow also became popular among the growing elite of Sri Lankan civil servants and professionals. Emulating the customs of the British, these families would also hire household help, and so class distinctions persisted in the room layout.

Suburban Middle Class

The ‘60s and ‘70s in Sri Lanka saw the growth of a new middle class as more people moved to the cities. In Colombo especially, this led to the rapid expansion of suburbs like Ratmalana, Nawala, Rajagiriya, and Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia.

This coincided with the rising popularity of the American single family suburban home, and the development of the Sri Lankan construction industry. Building materials became cheaper and were prefabricated, leading to very similar elements being used very often. Compared to the bungalows of the late colonial era, these houses had fewer internal divisions, and apart from the bedrooms, the other spaces flowed into each other. In her article on ‘tropical cosmopolitanism’, Anoma Pieris, professor of architecture at the Melbourne School of Design, describes how these houses, “which replicated popular American trends, were designed by draftsmen rather than architects, [and] built by local labour contractors. She adds: “Aesthetically, [they] bore no resemblance to the colonial bungalows of the early twentieth century or to the vernacular style that would soon replace them.”

Although colonial buildings had used new technologies conservatively, it was in this suburban movement that modern techniques were used to decisively break away from both pre-colonial and colonial building techniques.

Modernist Elite

Soon after independence, architects in Sri Lanka worked within a climate of strong anti-colonial sentiment. Like the suburban middle class, the urban upper class also rejected the classical, imperial features of British bungalow design. “The new architecture of post-colonial Sri Lanka was pioneered by architects like Minnette de Silva,” said Ashley de Vos, a contemporary Sri Lankan architect. “In order to develop a indigenous style, she told me to go back 400 years, and start from there,” he recalled.

The point was to remove all colonial influence, through both traditional and hypermodern styles, to create what De Silva called “regional modernism for the tropics”. While using European influences, they also took the traditional approach of working with local materials and techniques, and integrating nature with the built environment. Architects such as Minnette de Silva, Geoffrey Bawa, Visva Selvaratnam, and Valentine Gunasekara all individually contributed to the style commonly known as ‘tropical modernism’.

The growing popularity of mass-produced suburban homes irked Sri Lanka’s modernist architects. In the words of landscape architect, Bevis Bawa: “Our people after independence want to be independent; so [they] prefer to buy dozens of magazines, cut out dozens of pictures of buildings that take their fancy, take bits and pieces out of each, stick them together – and there’s a house.”

In response to what the Colombo elite saw as uncultured modernism, architects took tropical modernism in multiple directions. Although they had previously avoided colonial elements, by the ‘80s, modern architects blended features like pitched roofs, verandahs and courtyards with flowing spaces, clean lines and traditional decor. This very diverse and syncretic style, visible in upper class houses, boutique stores and luxury resorts, has become the contemporary, indigenous architecture of Sri Lanka.

According to De Vos, these elements weren’t truly Western, since they were adopted by the colonialists when building here, and tropical modernists are simply reclaiming local traditions by using them. In his buildings, he said, “shade is very important. People here walk in the sun with umbrellas. It’s hot, that is why we use tall trees and overhanging roofs.” But rather than becoming closed-off, sheltered spaces, they are “large, open rooms which connect with the outside.”