Rosemary was married with two sons, and working as a cashier at the Intercontinental Hotel—now the Kingsbury Hotel—in Colombo, when in 1985, her husband and son died in a car accident. Subsequently, her other son became a drug addict. At 64, she stopped working, but with no income, no pension, and no family to take care of her, she found herself on the street.

Although she was eventually found by the Department of Social Services (DSS) and sent to a privately run shelter, many of the elderly homeless are not so lucky. According to the National Secretariat for Elders (NSE), a subdivision of the DSS, over 15,000 people without homes are on their waiting list, and many more may lack access to these resources. While there are around 300 privately run homes for upper- and middle-class people, there are only six state-run facilities, with a total capacity of around 1,000. (Residents need to pay to find a spot in the private homes, but the state-run facilities are free).

Apart from these government facilities located in Kataragama, Gampaha, Kaithady, Saliyapura, Meerigama and Galgamuwa, the only other options for the poor are homes run privately by NGOs or religious organisations, such as the Shelter4Homeless in Piliyandala, where Rosemary would eventually find a place to spend the rest of her days.

Shelter4Homeless is a privately run home founded by Sanath Munasinghe, a philanthropist who vowed that he would help the homeless after an experience he had in 1988. “When travelling through Ratnapura, I ran into a frail-looking woman sitting on the side of the road,” he said. “She told me that she was on her way to the hospital but had gotten tired and sat down to rest.” He went to a nearby house to get her a glass of water, where the residents told him that the woman had been there for two days. “I was shocked. As a young man, it was an eye-opener,” he said. “And I thought about all the other people who were in need but had no one to care for them. It was then I told myself that when I turned 50, I would do something to help them.” After working in Canada as a Vice-President in the company, Best Buy, Munasinghe returned to Sri Lanka in 2016 to fulfil his promise, although he lamented that at 51, he was a year late.

Broken Bonds Of Kinship

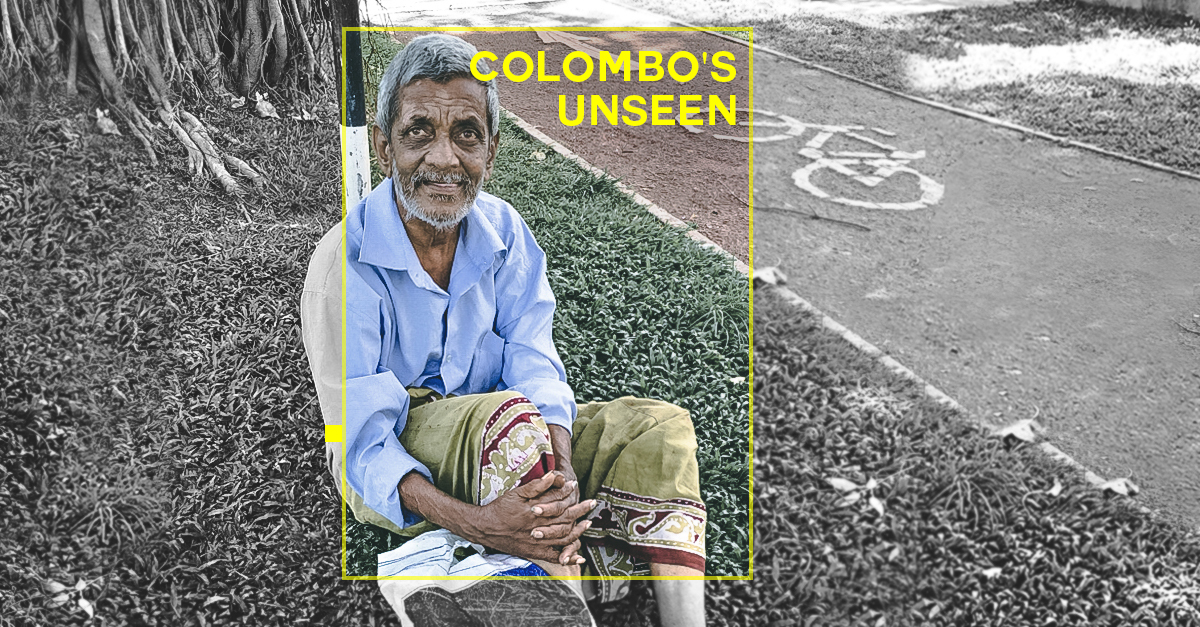

Although each homeless person has a unique chain of events that leads them to destitution, there are some common themes in their stories. Munasinghe noted that unmarried men and women who live from paycheck to paycheck, without a pension and without any remaining family, often find themselves in dire straits after retirement. Consider the example of Senavee, a 66-year-old woman who was rescued from a cemetery and brought to Shelter4Homeless. “My husband passed a long time ago, and I lived with my only daughter and her husband,” she said. “A couple of years ago, she died in childbirth and the child also died. When my son-in-law got remarried, he kicked me out of the house, and I had nowhere else to go.”

Additionally, people who work as domestic help sometimes become disconnected from their own families. Once they become too old to work for the family that employs them, they are left without either family to care for them. Neetha, 69, once worked as a domestic help in Maharagama. She says she has a son and daughter, as well as six grandchildren. “My daughter does not speak to me, and even though my son does visit me, he says that he cannot take care of me,” she said. “I am partially paralysed on my left side. But I’m lucky it’s not my right side, so I’m still able to do things with my right hand,” she added jokingly.

In contrast to many industrialised countries, an understanding of ‘home’ in much of the developing world is more intimately tied to family and kinship than it is to shelter. Security comes not necessarily from ownership and control, but from the responsibilities—and inbuilt security—of kinship. This is why the personal tragedies that transpire throughout life often affect those without family the most.

Ajith, 66, was a businessman in South Africa, and had grown distant from his wife and children back home. When he returned to Sri Lanka, he too was abandoned by his family. But like Neetha, he was not bitter about this. “My children are successful now, and I’m glad they are doing well,” he said.

Life At The Shelter

Located on the shores of the Bolgoda Lake, the shelter is a quiet sanctuary far from the commotion of the city. “The Catholic Church owned this abandoned building,” said Munasinghe. “It was just walls and a roof back then. There was no electricity or plumbing, but since they knew I wanted to open up a shelter, they offered it to me to renovate and use.”

Initially, Munasinghe thought that he could just pick up people off the street. However, he found that this would have some legal ramifications. Now he works closely with the Department of Social Services, specifically its facility in Mirigama. Since this home has trained medical staff, they prioritise those with serious health problems, and send healthier people to other homes, such as Munasinghe’s.

Health complications can also be the trigger that leads to homelessness, as was the case with Subramaniam, 72, who was taken to Kalubowila hospital for an operation by his children. They didn’t return to collect him, and he spent two years begging on the street, before being found by the DSS.

After living on the streets, it sometimes becomes difficult for residents to readjust to the routines of normal life, with a roof over their heads. “Sometimes they can’t use the shower, or don’t know how to shave, so we help them with this relearning these things,” said Munasinghe. “It’s almost like rehabilitation. When a homeless person has finished eating, they often just throw their food on the ground. There was one man who stayed here who would do just that after every meal.”

At Shelter4Homeless, the residents are provided with three meals a day, a bed and shower, regular health checkups, and transport to the hospital when needed. “We give them all the basics, but I wish they had more activities to do,” Munasinghe said. “We’ve recently got some radios from a donor, but other than listen and argue about the volume of each other’s music, they don’t do much else through the day.”

The Shelter4Homeless accepts donations in the form of sponsored meals. Donors can make and bring food for the residents, or can pay the cost (Rs 375 per head) for a day’s meals.

Website: http://www.shelter4homeless.com/