The Slave Island area of Colombo, also known as Kompannavidiya, has a rich history that dates back to 1505. Best known for its multicultural makeup and the distinct architectural style of its old buildings, Slave Island has always had a distinct identity. This ethos is being slowly replaced by a newer, more modern character.

At present, several development projects are underway in the area, under the Government’s USD 287 million Colombo Regeneration Project. These projects include a housing relocation project for old-time residents and the refurbishment of the Slave Island railway station.

Most of the buildings in Slave Island share common features such as sweeping arches, and intricate woodwork interwoven with metal embellishments. The best examples of this Victorian style of architecture include the railway station and the De Soysa building.

Built in the late 1870s by the famed philanthropist, Charles Henry de Soysa, De Soysa building is one of the heritage structures in the epicentre of the city that has been marked for demolition.

The De Soysa building is largely run down. The paint is peeling, the hollow walls have become a haven for mice, the roof leaks and the stairs creak. Even though it is dwarfed by the vertiginous constructions in the area—and has certainly seen better days—it still survives.

Its compartmentalised spaces—originally intended to function as a two-storeyed block for shophouses, with shops on the ground floor and residential spaces on the first floor—have managed to house generations of families, who have lived here their whole lives. A number of small businesses, shops and homes built decades ago within the unrefurbished walls of the De Soysa building, continue to flourish to this day.

Finding The Colombo Central Club

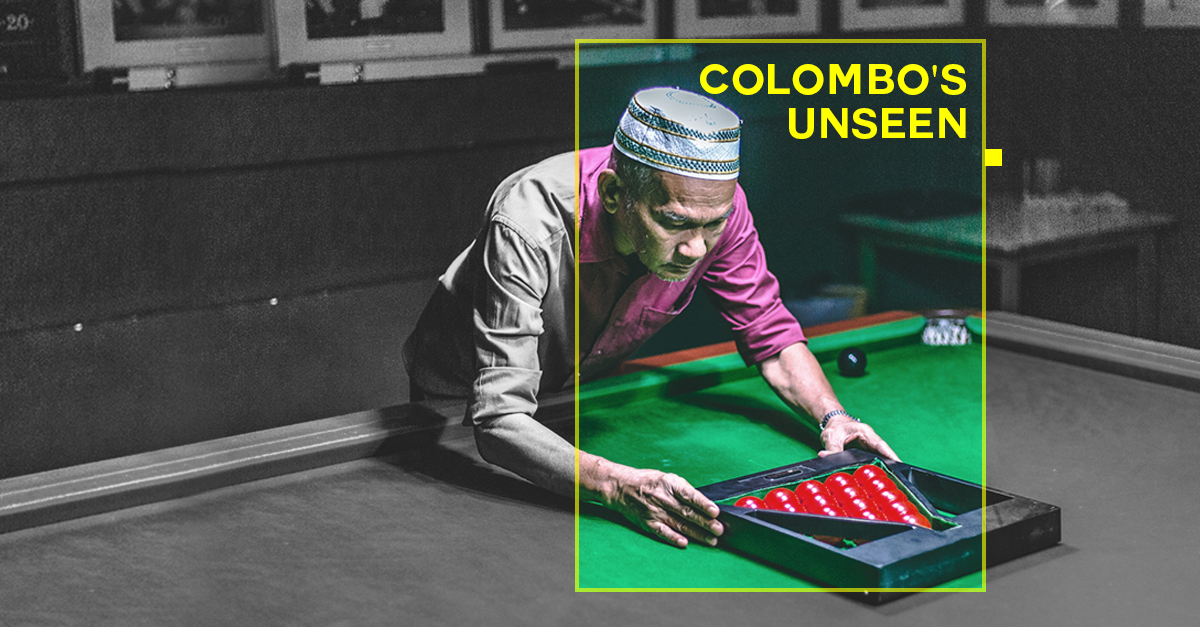

One of the building’s longest occupants is also perhaps its least known: Sri Lanka’s oldest surviving billiards club. Located in one of the narrow cubby hole spaces of the De Soysa building, it is over 76 years old.

When Abdul Rahim, a self-taught billiards and snooker player, started the Colombo Central Club in 1946, it held the distinction of having one state-of-the-art billiards table. The table was the cynosure of the club.

Now, the club in its original form is no more. In its stead is The Cue, a billiards and snooker cafe started by Rahim’s great grandson, Noor Zulsky Passela.

Abdul Rahim was a businessman. He was a venture capitalist of his era, self-employed and of financial means. Passela reminisced that soon after his marriage, Rahim and his new family moved into a small house, adjacent to the De Soysa building. With his workplace close to home, Rahim went on to make a name for himself as the owner of the Colombo Central Club. Eventually, he built a larger home for his family as well.

However, his home was one among 70,000 households on Java Lane in Slave Island that were demolished by the government in 2014, forcing the family to move into the De Soysa building. The demolition splintered the community. Passela claimed that his family never received compensation for their destroyed property.

After Rahim passed away, his two sons, N. A Rahim and N. J Rahim, would carry on the legacy of the club for several years and experience its golden era.

With time, the families expanded and moved away. After their grandfather’s home was demolished, one part of the family moved into the De Soysa building. But with no one to maintain the club and premises afterwards, the Central Club was shut down in 1971. The table was turned into an ironing board and then donated to the Moors Sport Club. It remains there to this day with a plaque that reads ‘The Rahim Brothers Table’. Interestingly enough, Sri Lanka’s first international billiards champion, M. J. M. Laffir, practised at the old club.

It would take several more years for Passela, the current owner, to take over the establishment and rekindle his family’s tradition. After having arrived to take care of his ailing father, Passela fashioned the Colombo Central Club into its modern-day avatar of a cafe. It also serves as the official headquarters of the Sri Lanka Association of Billiards and Snooker.

Where Things Stand Now

Our chance discovery of Colombo’s oldest billiards club led us down a path rich in history, memory and tragedy. It is a story of resistance, and of a community faced with the inevitability of change, struggling to hold on to their sense of identity. Passela’s cafe, built to honour the legacy of his grandfather and uncles, serves a dual purpose. It was built in the hope of preserving a past that stands to be lost, and to further a family tradition, all tied into a singular passion for sport.

This is embodied in the Wall of Honour that adorns an entire section of the cafe. Etched with the names of champions and record setters going back to 1948, this Wall of Honour serves as a reminder of past victories and accomplishments to new players. New additions are included for everyone to see. “This [wall] is as old as the club itself,” Passela said, proudly.

Facing the wall are family photos of Passela’s uncles, and their achievements and awards. His uncles, the Rahim Brothers, were celebrated airmen as well. The cafe is not only a museum for Passela’s family but also for the entire community in Slave Island.

There is a clear difference between pool, the popular recreational game, and billiards. “Anyone can learn to play pool. But you need years of experience and discipline to learn billiards and snooker,” Passela explained. “Once you get into billiards and snooker, you will never play pool again.”

Before a game, the billiard balls are set up using a triangle rack. Once the table is set, the first player will break the set up, commencing the game. There are numerous ways to play the game. Once a game is opened, a professional pair of players will take less than 15 minutes to finish the session. But if you’re just learning the ropes—or edges, in this case—things tend to drag on.

Passela has just one billiards table, much like in his grandfather’s club. “We have several tables that are not in use anymore due to the lack of space. It would be good to have more space but we are making do with what we have,” he said.

According to Passela, the club welcomes anyone who has a genuine interest in the game. “We don’t care [about your] ethnicity as long as you know how to behave,” he said. “You cannot smoke near the table, you cannot drink and you cannot fight. You fight outside. We have some good boys here. Even those who have gone abroad for work remember to return here during their holidays for a friendly game.”

The goal of billiards is to pocket the balls in a given order. The stack is broken apart, separating the multicoloured collective. Much like the multi-coloured billiard balls, the close-knit community in Slave Island is slowly being stripped of its sense of unity. The threat of being evicted and forced to uproot their livelihoods is ever present.

Some reports suggest that the demolition of the building may have been suspended for the time being. However, Passela remains pessimistic about the future.

“After me, I don’t know whether the club will go on,” he said. “If the government forces us to move again, if they want to demolish this building, it will all be for nothing. I will have to sell everything. We have to think of the children and the future, don’t we?”