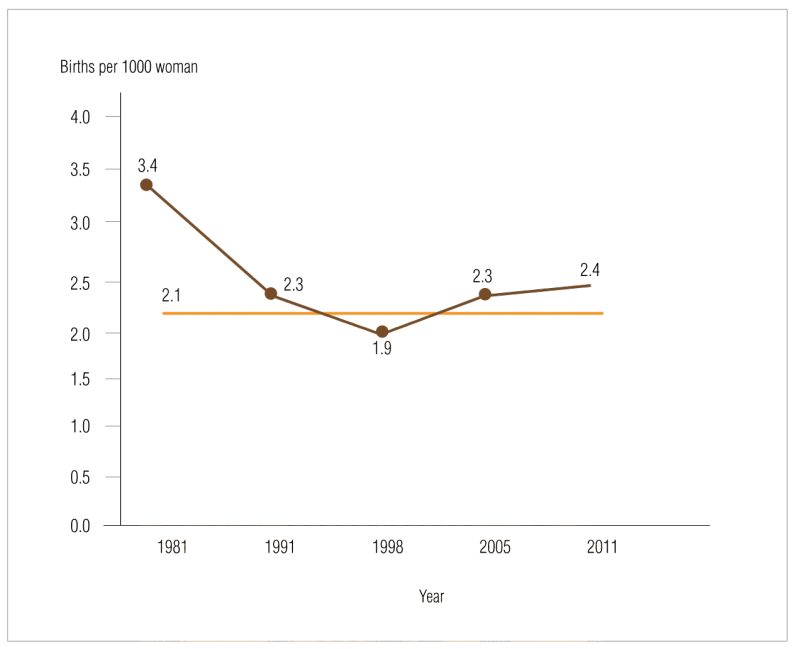

This may sound strange, but Sri Lanka is the only country in the region with a rising fertility rate. According to the Census on Population and Housing report released in 2012, the “Government in its population policy statement issued in 1991, set… a TFR (Total Fertility Rate) of 2.1, to be achieved by the year 2000.” As of 1998, Sri Lanka’s TFR was 1.9, making it the only country in the South Asian region to “achieve the level of replacement fertility before the end of last century, and ahead of the targeted time frame.” Oddly enough, ever since 1998, Sri Lanka’s fertility rate has been on the rise, reaching 2.3 in 2005 and 2.4 in 2011. Before we can ask why, however, let’s take a look at what the fertility rate really means.

What does TFR mean?

According to Dr. Sanjeewa Godakandage, Consultant Community Physician of the Family Health Bureau, the TFR is, quite simply, a measure of the “average number of children per woman.”

The Census report defines it as the “measures (of the) average number of children born to a woman during her entire reproductive period,” while the UN has a more elaborate definition: “the average number of live births a woman would have by age 50 if she were subject, throughout her life, to the age-specific fertility rates observed in a given year. Its calculation assumes that there is no mortality.”

A Further Breakdown

Here’s what the report outlined:

- As per 2012 census data, TFR value estimated is at 2.4 live births per woman in 2011.

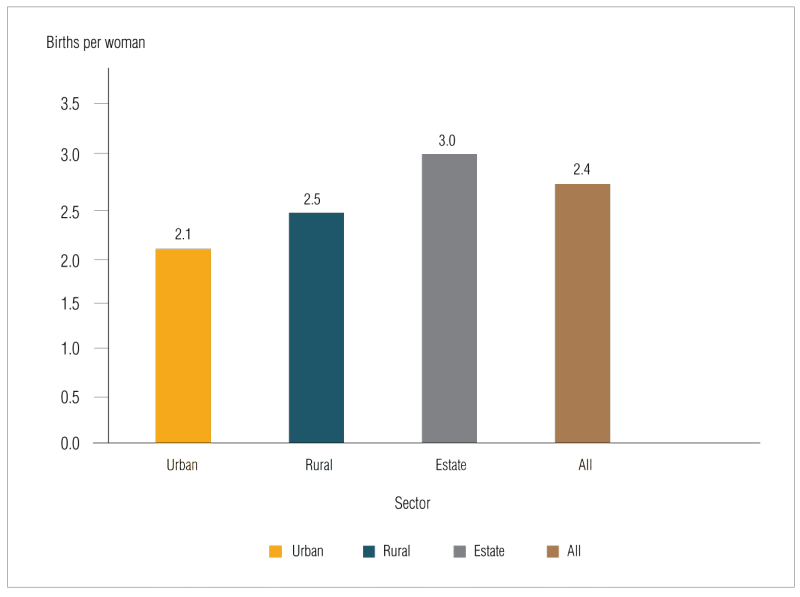

- Going by sector – the estate sector women reported the highest TFR of 3.0. Rural women reported 2.5 while urban women have the lowest TFR of 2.1, which means that only the urban women are at the replacement fertility level while the women from the other sectors are at a higher level.

- Change in TFR – The estate sector has the highest increase in change in TFR from 2005 to 2011, demonstrating about half a child increase on average. For rural women, it increased from 2.3 to 2.5 while for urban women it has decreased from 2.2 to 2.1. This decrease, however, was not enough to off-set the national TFR value.

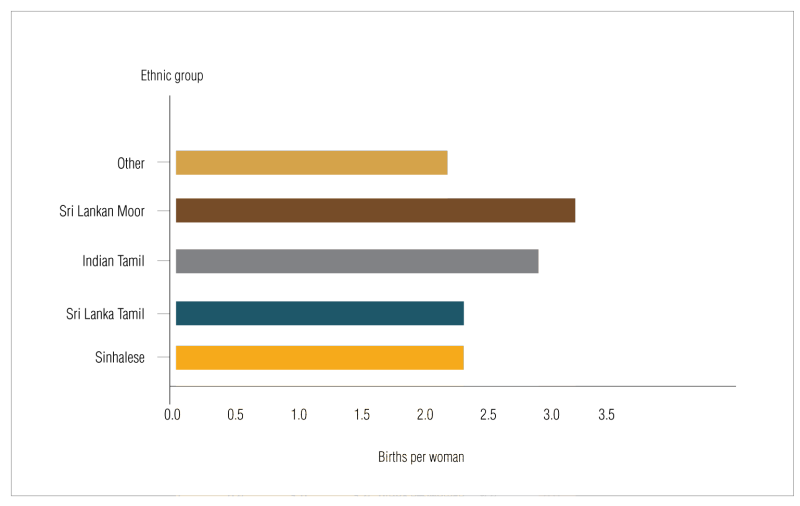

- Ethnicity – The Sri Lankan Moor ethnic group reports the highest TFR of 3.3 live births in 2011. Sinhalese and Sri Lanka Tamils have the lowest TFR of 2.3 live births, which is around one child lower than the Sri Lanka Moor group. Indian Tamils are at 2.9, while the other category, which groups together the Burghers, Malays and Sri Lanka Chettys reported 2.4 live births

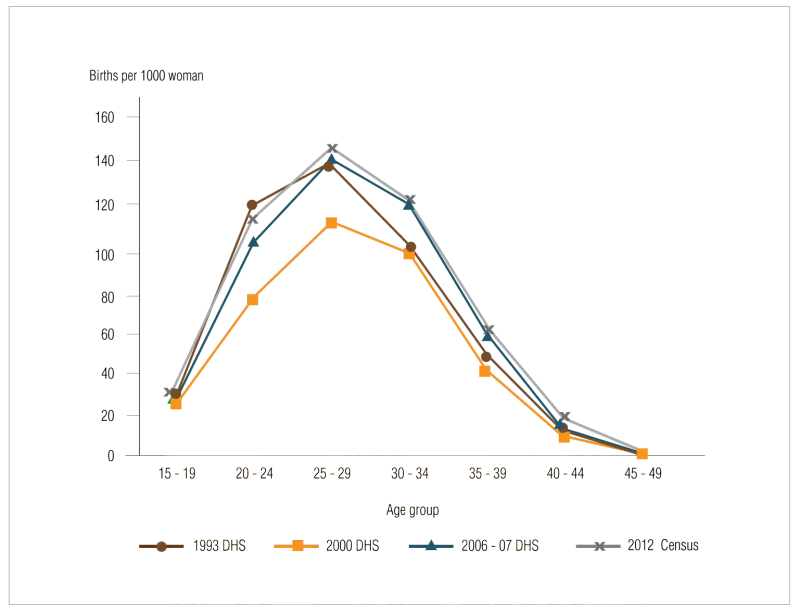

- Age – Age specific fertility rates declined greatly from 1993 to 2000. Older and younger women experienced a decline in fertility during that period, but with the dawn of the new century, the age pattern of fertility of all ages, except 45 to 49, increased unexpectedly.

- There is an increase in the teenage fertility rate (15 – 19). During the period of 2000 and 2006/7, there was a 3.7% increase, while the latest data reports an increase of 12%. While teenage fertility has declined in most developing countries, it has increased in Sri Lanka.

- Since 1960, the TFR in Sri Lanka has been on a downward trend and had reached 3.4 live births per woman in 1981. By 1994, it had fallen to 2.1 and by 1998 to 1.9. The TFR has been on the rise ever since reaching 2.3 in 2005 and 2.4 in 2011, increasing the TFR from being well below the replacement rate to being well above it.

Why has the TFR in Sri Lanka increased?

Professor Indralal De Silva of the Department of Demography, University of Colombo explained that many factors have come together to contribute to the rise in the TFR. Some of these include:

- Decline in average age of marriage. On average, females get married at the age of 23.5 while males get married at the age of 27.7 years. This, according to Professor De Silva, is the main reason for the increase in TFR.

- Natural disasters such as the tsunami and conflicts like the civil war. “Such events killed off a lot of our children. As a result, parents have revised their fertility preferences,” Professor De Silva said.

- Because certain minorities feel threatened, conception has risen to increase the number of people belonging to the minority.

- Treatment for subfertility.

- Remittances coming in from the Middle East which helps support larger families.

- A sizeable proportion of females are not working. We wrote an article related to this not too long ago.

- Groups promoting pronatalism

- Schemes that promote fertility by providing incentives and benefits for certain groups to have more children.

- Withdrawal of abortion facilities

- Weakening of contraceptive programs.

Speaking to the Family Health Bureau, it was understood that while there is no real consensus as to why the TFR has increased, there are several contributing issues. Where family planning is concerned, it was pointed out that after the tsunami and the civil conflict, there has been a change in attitudes towards family planning and that their needs are greatly under-addressed. Additionally, adolescent pregnancies are now higher, which the Family Health Bureau attributes to a change in societal values. They also pointed out that although abortion is illegal in Sri Lanka, the crackdown on these facilities has also contributed. There is also increased pressure by social and religious groups against family planning as well as a reduction in the age of marriage. On the whole, the Family Health Bureau added that this increase in fertility has been observed in all ethnic groups in Sri Lanka.

What does a rising TFR signify?

Speaking to Professor De Silva, it was understood that a rising TFR has several serious implications, including:

- Population increase – a rising TFR means a rise in population, and in this case, a significant one. As the population increases, there is a greater pressure on land, water, the environment and natural resources.

Greater burden on tax payers – with more children in society, added to the elderly population, there are more dependents. More dependents increases the burden on the tax payer.

- Lower female labour participation – More children equals to less women contributing to the economy. For that matter, even as of now, there are fewer women participating in the labour force. According to the UN, women who have several children “find it more difficult to work outside the home, thus having fewer opportunities to improve their economic and social status and that of their families.” As a result, getting out of poverty for low income households with many children is often difficult, in comparison to those families with less children.

Is this something our policy makers are worried about?

Although they should be, they aren’t really. Professor De Silva noted that there has been no serious discussion of what this implies on the part the Government. “The policy makers have not paid much attention to these particular areas,” he added.

Featured Image from CRC.ORG