It’s not a topic we dwell on often, but in many cases, there’s an interesting story or two behind how some of our towns and villages got their names. Usually, these stories are based on geographical locations, or the various people who are said to have lived in these areas. The stories can also be quite rich in historical references. Most of them have been passed from generation to generation in the form of folk-tales. It’s often advisable to take these with a grain of salt ‒ as storytelling back then sometimes involved a bit of exaggeration (or thrilling detail) to evoke interest and keep the story alive. At the same time, one can use these stories to get quite the insight into the evolution of culture and lifestyles, from back in the day.

After consulting historical texts and talking to elders with plenty of knowledge on the subject, we gathered together some interesting stories on how certain places in Sri Lanka acquired the unique names they have today.

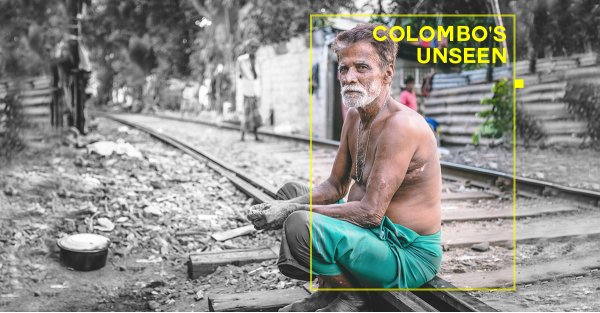

Colombo [Ko-lum-buh]

The ancient ‘Raajaavali’ text refers to present day Colombo as ‘Kalanthota’ and ‘Kalani Gamthota’. As a matter of fact, ‘Colombo’ only came into being following the Portuguese invasion back in 1505. This name is said have to come from a certain fruitless mango tree ‒ hence kola (leaves) + amba (mango), an indirect reference to a mango tree which is devoid of fruit.

According to the Portuguese, however, Colombo could also be a reference to Colombus. The ancient explorer Ibn Battuta is also known to have referred to Colombo as ‘Kolaanpu’ or ‘Kalanpu’. European pronunciation probably had something to do with ‘Colombo’ as well, and Portuguese documents from that era often refer to Colombo as ‘Kolahamba’, ‘Kolomba’ and ‘Colahmbo’.

Colpetty [Kollu-pitiya]

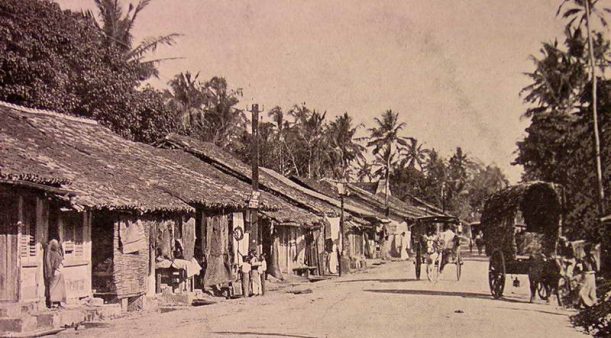

The Kollupitiya bazaar from back in the day. Image courtesy lankapura.com

The Kollupitiya bazaar from back in the day. Image courtesy lankapura.com

It’s hard to imagine the Colpetty of today being referred to as ‘Barandeniya’, but apparently that’s the name Colpetty went by, back in the day. An area that was not overly crowded, Colpetty had lush fields and both palm and cinnamon fields in abundance. This area was often frequented by traders (who probably had to deal with ancient traffic jams) going about doing their business in rickshaws, bullock carts, and the more luxurious horse drawn carts.

At the time, there had also been a palm-estate controlled by a local by the name of ‘Ambanwela Appuhaami’ who was biased towards the Dutch. With time, the estate started to expand by gradually invading the land-plots next to it ‒ which resulted in a public uproar, where people took to the streets screaming ‘kolla-ka-pitiya’ (translates to ‘land which was robbed’). This name evolved into the present Colpetty ‒ for that matter, to this day the area surrounding St. Michael’s Church and College is referred to as ‘Polwatta’, or palm estate.

Nittambuwa

Chances are you might have heard of ‘Nittawan’ before. They are said to be an evasive, sheltered group of people who used to live in caves and tunnels. Although excavations are yet to yield scientific proof that Nittawan existed (they must have really known how to hide), there’s plenty of folklore and tales that have been passed from generation to generation which speak about these people. They are also said to be smaller in size and have bodies covered with hair and long nails (something not too far from a Tolkien novel if you think about it…).

The Nittambuwa close to Gampaha and also the Niththawela, which is in close proximity to Kandy, could both be references to these people as well.

Kirulapone

A name that is said to have come into being in the Kotte era, this could very well be a reference to the fact that one could see the King’s castle from this area, hence Kirula-pene (the crown is visible). Kirula-pene has evolved into the now Kirulapone.

Kurunegala

The Kurunegala town, with the famous ‘gala’ (rock) in the background. Image courtesy wayambatourism.lk

The Kurunegala town, with the famous ‘gala’ (rock) in the background. Image courtesy wayambatourism.lk

Kurunegala, also known as Hasthishailapura in Pali, or Athugalpuraya, is renowned for the huge mountain of rock in the middle of the city. There’s a theory that the name came into being as the mountain resembled an elephant by the name of ‘Kuru naa’. There’s an alternative version of this which states that Kurunegala could depict either short people (Kuru) or the Indian Kauravs, who are said to have relocated to that area.

Lamasooriya

A village in Hanguranketha, which is a part of the Nuwaraeliya district, Lamasooriya has its own story to tell . It is believed that the government appointed sub-agent for that area had been an officer by the name of C. J. R. Le Mesurier. The village that he resided in was later renamed Lamasooriya (a Sri Lankanised version of ‘Le Mesurier’) in remembrance of his services to the area ‒ which included penning a book on up-country laws, called ‘Neethi Nighanduwa’ co-written with Tikiri Banda Paanabokke of Dumbara.

Weeraketiya

A statue of King Valagamba next to a statue of the Lord Buddha, at the Golden Rock Temple, Dambulla. Image courtesy srilankaview.com

A statue of King Valagamba next to a statue of the Lord Buddha, at the Golden Rock Temple, Dambulla. Image courtesy srilankaview.com

Located in Hambantota, Weeraketiya got its name thanks to King Valagamba, who is said to have hired forces for his armies in the Weeraketiya area ‒ hence the name which translates into ‘gathering of heroes’. Weeraketiya also happens to be the birth-place of Sri Lanka’s former president, Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Bothale

This village also happens to be the birthplace of Sri Lanka’s first Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake. Bothale is famous for not only for being home to the Senanayake mansion, but also for its graphite mines. As for how the village got its name, the story goes back all the way to the third century, A.D.

It is believed that Prince Gotabhaya set off to Aththanagalla in search of the body of his dead brother, King Sirisangabo, who had taken to the forests after being dethroned. On the way, the troops took a break in Vaharepola, where Prince Gotabhaya realised that the bo-plant he had with him had started to root. From then on, Vaharepola became known as Bothale (Bo-thale, in reference to the plain where the Bo plant rooted). There is, however, another story that the name ‘Bothale’ came into being following the relocation of people from 18 castes to the area, hence Boho-thale (the plain with many people).

Kundasale

Kundasale is a village that is located on the left bank of the Mahaweli river, about 4 miles away from Senkadagala. There is a rather interesting story about how this village got its name, which is described in detail in D. P. Wickremasinghe’s ‘Maga Digata Jana Katha’ (folk-tales along the way).

Back in the day when King Wimaladarma the First was ruling over Sri Lanka, an Indian astrologer predicted that a war was going to take place between the sun and the moon (today we have trouble predicting when the next rainfall is, so go figure!). Using advanced calculations, he was also able to foresee how a certain ‘kundalaabharana’ (piece of jewellery) worn by the moon god was going to end up falling into the Mahaweli.

Having located the approximate area where the kundalaabharana was going to fall at a village called Gurudeniya, the astrologer wasted no time and came to Sri Lanka in search of it. Upon reaching Gurudeniya, the astrologer stopped at the Gurudeniya temple for the night, where he explained in full detail what he was in search of to the head monk of the temple. Little did he know that the monk also excelled in astrology, and the monk was able to calculate the exact place the jewel was going to fall.

After bidding farewell to the monk, the astrologer continued his quest, but upon coming to the place he realised that someone else had beaten him to the discovery and had already taken off with the object he was after. The astrologer was so devastated by this that he ended his life by jumping into the Mahaweli.

The kundalaabharana was in the possession of the monk from the Gurudeniya temple, who then offered it to King Wimaladharma, who was so ecstatic that he used it to mold a miniature platform to rest the sacred tooth relic of the Buddha. With time, the Saalaa area from which the kundalaabharana was recovered from was renamed as Kundasale.

Oluwaawaththa

An artist’s impression of the demon Ritigala Jayasena, whose head, it turns out, is the ‘oluwa’ behind the name Oluwaawaththa. Image credit: wishmithawishwaya.com

An artist’s impression of the demon Ritigala Jayasena, whose head, it turns out, is the ‘oluwa’ behind the name Oluwaawaththa. Image credit: wishmithawishwaya.com

As far as folktales go, there is a rather graphic story behind how Oluwaawaththa in Kandy got its name. Giants and demons are generally known to be feisty ‒ especially the latter. According to the tale, a demon by the name of Ritigala Jayasena and the giant Gotaimbara had had a face-off where the giant had used his immeasurable physical energy to kick the demon in the head (picture that!). The kick had been so ferocious that it had severed the demon’s head on impact (we don’t advise that you try to picture this bit, or even try it at home against annoying siblings). It doesn’t stop there though, as the severed head then sailed from the point of impact, only to smash into smithereens upon landing on a rocky plain.

From then on, that area got its name, ‘Oluwaawaththa’ ‒ meaning ‘the land where the head landed’. The brains of said head were also said to have scattered into the nearby area ‒ giving it the name Thulpegoda. (Thul – the grey matter of the demon’s noggin, Pe – seen, Goda – land or general area).

Mythology, invasions and history have come together to create the curious blend that translated itself into the names of our towns. Although many of the stories have may gotten lost in time, it is definitely (sometimes even PG) entertainment.

Featured image courtesy lankapura.com