If you don’t know it yet, your daily rice and curry packet is about to get a whole lot lighter. Sri Lanka is running out of rice and that spells a lot of trouble for the country—especially for farmers involved in rice production and households whose income levels cannot handle the increased prices of rice. The severe drought that hit the country late 2016 and early 2017 has severely affected the 2016/2017 maha harvest, causing a massive 45 percent reduction in the production of the paddy crop. In light of the severity of the problem, the FAO and the WFP have released a special report on the crop and food security situation in Sri Lanka. The report has estimated about 900,000 people as being borderline food insecure because of the drought and reduced crop production. The 2017 aggregate paddy output is forecast in the report at 2.7 million tonnes, which is almost 40 percent less than last year’s output and 35 percent lower than the average of the previous five years.

It’s not just rice that’s affected either, but vegetable crops and cereal crops, too. To meet the demand for grain would require an import of 1.78 million tonnes of cereal, including 998,000 tonnes of wheat, 100,000 tonnes of maize, and 686,000 tonnes of rice.

It doesn’t just end there. A reduced crop for 2017 can affect the 2017/18 maha planting season from September to December. The current problem is severe enough that it may cause ripple effects far down the line. If the government doesn’t help farmers with seed for this season, there will not be sufficient crop planted for the next year. If farmers sink themselves into debt to last out this drought, it will affect paddy production years down the line.

Who’s To Blame?

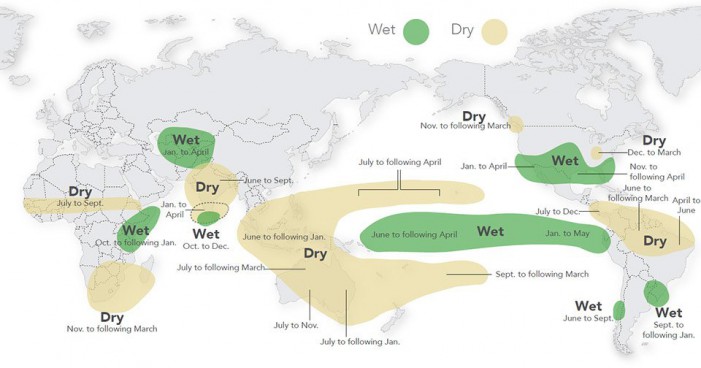

The finger of blame has swung from El Niño to La Niña, but the truth might be a bit more complex. Besides, El Niño was supposed to bring us extra rainfall, which it did for a while.

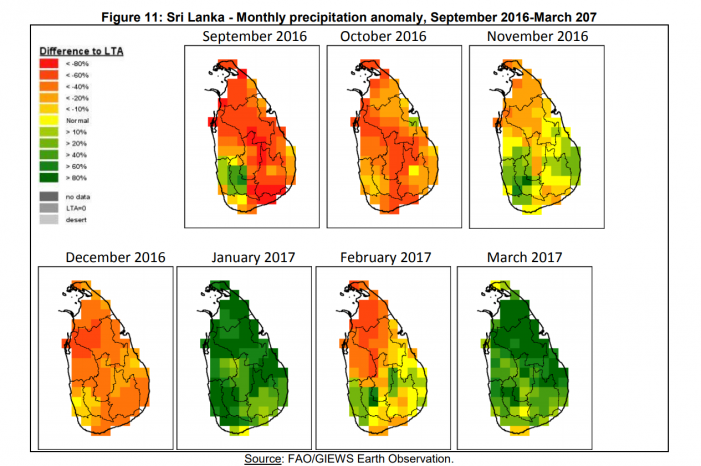

El Nino was supposed to bring in extra rainfall to Sri Lanka. Image source: FAO

K. H. M. S. Premalal, Director of the Department of Meteorology, holds climate change responsible. In an interview early this year, he stated that Sri Lanka has started experiencing a variability in rainfall patterns. He says that when it rains, it rains more heavily, and when it doesn’t rain, the dry weather continues “longer and at a higher intensity.” He blames human activities for these climate changes—felling of trees around the world and on the island, filling of land, and construction, he says, are triggering factors.

And trigger they did. The 2016 drought was the worst to hit Sri Lanka in 40 years.

Not A Surprise

The severity of the drought was not something anyone could have predicted. But the fact that conditions were bad and getting worse, was not a surprise. If the government had paid attention to the data it gathers (and if it gathered more data), it could have seen trouble looming.

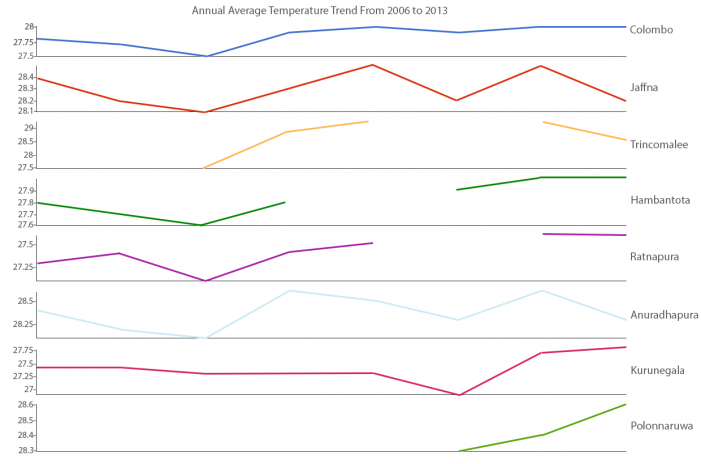

The Department of Statistics has a series of measurements of the average annual air temperature at observation stations across the country. They have only published data till 2013 and some of the data points are missing, but the graph shows a general increase in average temperature across the island.

Average temperature around the country has been increasing over the years. Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Even if the increments are in decimal places, global warming still has severe consequences, no matter what Trump says. This web app shows projections for countries that may suffer from heatwaves in the future, and Sri Lanka is right in the middle of it all.

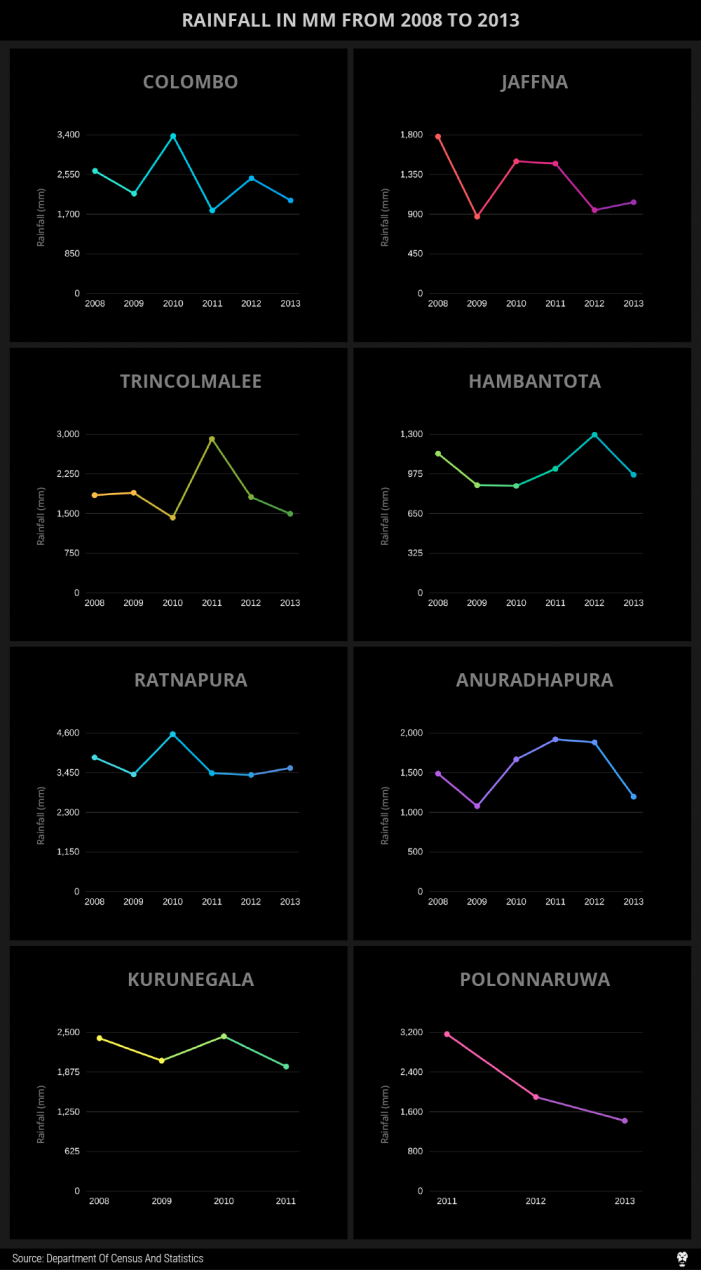

The story is remarkably similar when looking at rainfall over the years. All the data points are not available, but there is a marked decrease in average annual rainfall across the country.

Average annual rainfall has decreased.

Sri Lanka has been showing anomalies in weather and rain patterns for a while. It’s safe to assume these anomalies will continue. When it rains, it will rain more than usual, and when it’s dry, it will be drier than usual.

Monthly precipitation anomalies. The variation from the Long-Term Average (LTA). Image from the FAO report

Work The Data

There is a pattern being established here, and the government needs to work the data to start optimising and predicting the effects of weather change on agriculture. If not prediction, it at least needs to understand that it can no longer depend on the status quo. Things may get worse for Sri Lanka, and there needs to be some sort of planning in place to deal with it, instead of the reactionary way things have been done over the last two years.

Governments around the world have been using big data for a while to help optimise agriculture. Colombia a few years ago had trouble with their own rice crop. Between 2007 and 2012, the country’s rice yield dropped from six to five tons per hectare, and they couldn’t figure out the cause. Scientists at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture approached Colombia’s National Federation of Rice Growers for their harvest monitoring records, used advanced algorithms to comb through the data and uncovered patterns that they compared to weather records. The results they got were very site specific, but they found certain weather factors were causing the decrease in yield of the crops. For some fields, the yield was limited by stronger solar radiation, and for others, a different variety of seed would yield better results. The project won the UN Global Pulse’s Big Data Climate Challenge in 2014.

All over the world, startups are popping up aiming to change the way agriculture works. Companies like Climate Corp and Encirca offer decision support tools for farmers, and CropIn uses analytics to provide insights to farms in India. A large percentage of food produced is generally wasted, and big data can help eliminate inefficiencies in the whole system.

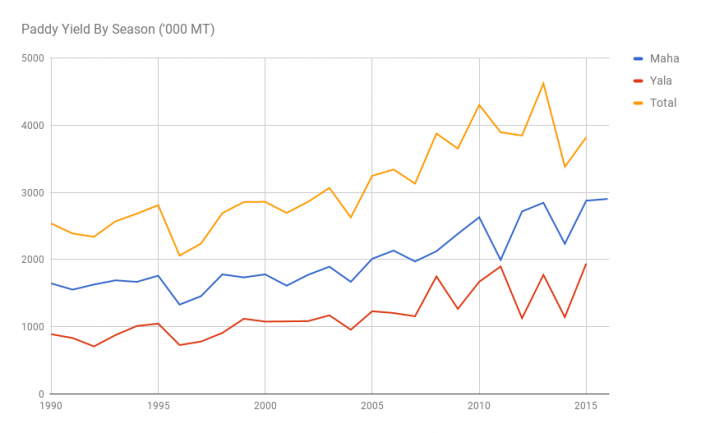

While Colombia’s rice farms yield about six tons per hectare on good days, Sri Lanka averages about 4417 kg (4.8 tons) a hectare. They also have a very significant variation when it comes to total production every year. The yield graph looks like the back of a geriatric stegosaurus.

Paddy yield can be unpredictable. Source: Department of Census and Statistics

Data and technology are revolutionising agriculture worldwide, and Sri Lanka needs to step up its game. No one can control the weather, but using the data, we can at least plan for what’s coming, eliminate waste, and fine tune our processes. Our reservoirs are not even at half capacity now, and with a poor planting season predicted for this year, the country needs to plan well to stay out of trouble.

Featured image courtesy blog.ciat.cgiar.org