For those not properly acquainted with the country’s intellectual property laws, applying for a patent may seem like a terrifying prospect. But fear not – the National Intellectual Property Office of Sri Lanka has several mechanisms in place to make the process considerably smoother, starting with this form, which provides a checklist of everything you need to have in order when doing so.

The law governing patents is contained in the Intellectual Property Act of 2003. Image Credit: Roar/Minaali Haputantri

But first things first – is your invention patentable at all? This depends on whether or not the invention in question fulfills the requirements laid down in Chapter XI of the Intellectual Property Act, No. 36 of 2003.

Patentability

An invention – according to Section 62 (1) of the Act – is an idea that provides a practical solution to a specific problem in the field of technology. It can take the form of a product or process.

But not every invention is patent-worthy, and a given invention must fulfill a very specific set of criteria in order to be granted a patent.

Section 63 of the Act states that an invention is patentable if:

- it is new,

- involves an inventive step,

- and is industrially applicable.

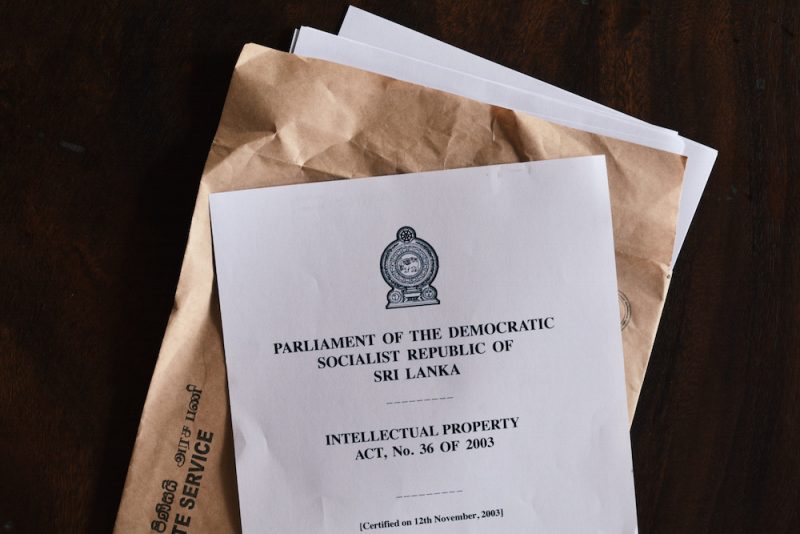

When the lego brick was invented in 1932, no one had seen anything like it before. Image courtesy: Lego

Let’s examine each of these requirements in turn.

The Novelty Requirement

According to Section 64 of the Act, “an invention is new if it is not anticipated by prior art”.

What this means, in simpler terms, is that the invention should not be something that has already been disclosed to the public in any manner or form, whether in Sri Lanka or elsewhere.

An Inventive Step

Section 65 tells us that an invention will involve an inventive step if, having regard to the prior art, such an invention would not have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art.

In other words, the invention in question should be the result of its inventor having taken an unanticipated step forward from the state of the art as it then existed.

Industrial Applicability

What this requires is simple – your invention must have a practical use. As Section 66 puts it, an invention will be considered industrially applicable “if it can be made or used in any kind of industry”.

While methods of treatment cannot be patented, medicines used in the process can be. Image courtesy: Rapps Pharmacy

But you’re not quite safe yet. Section 62 (3) of the Act lists out the types of inventions that cannot be patented, among which are mere discoveries, mathematical methods, plants, animals, methods for doing business, and methods of treatments of humans and animals (although products used in any such method – like devices and medicines – can be patented).

Who Owns Your Patent?

Section 67 of the Act states the right to a patent shall, as a general rule, belong to the inventor or, where applicable, joint inventors of the invention in question.

Where two or more persons have made the same invention independently of each other, the right to the patent will belong to the person whose application has the earliest filing, or, where applicable, priority date.

Section 69 qualifies this by providing that an invention made by an employee or worker in the course of their work shall, in the absence of any provision to the contrary, belong to the employer or the person who commissioned the work. In the event the invention goes on to acquire a much greater economic value than what was reasonably foreseeable, the employee or worker in question may be entitled to remuneration.

Under Section 70, the inventor retains his right to be named as such in the patent, although he can choose not to.

You Have A Patent – Now What?

A patent, once granted, may be valid for up to twenty years following the filing date of the application for its registration, but it does not last that long by default.

In order to keep a patent in force, its owner must pay an annual fee, starting at the end of the second year following the grant of the patent. This fee is, however, one that can be paid in full at the start.

When the Post-it was patented, its owners were able to not only exploit their invention themselves, but also license it out. Image courtesy: ioeducation.com

A patent, while in force, confers upon its owner a number of rights, which are listed in Section 84 of the Act. They are, namely, the rights to:

- Exploit the patented invention,

- Assign or transmit the patent, and

- Conclude license contracts with regard to the patent.

So if you’re still with us, congratulations! Having given yourself an education on the ins and outs of Sri Lankan patent law, you’re well on your way to getting one – provided, of course, you have the invention to go with it.

Featured image credit: Roar/Minaali Haputantri

This article was brought to you by Dialog