The current judicial system of Sri Lanka was established by the Judicature Act No 02 of 1978 and was entirely influenced by the English Law and Roman-Dutch Law. It originated during the Dutch rule of Ceylon, and further evolved in the British Period with the enactments of the Charters of Justice of 1801 and 1833. But what you may not know, is that the ancient kingdom of Kandy (1593-1815), which was governed by the distinctive Sinhalese Law, had its own elaborate judicature.

A group of Kandyan Chiefs from Tennent’s Ceylon, published in 1859. Image courtesy karava.org

Gamsabhava

The gamsabhava, or village tribunals, consisted of the village elders, and often proceeded at an ambalama, or under a tree. These tribunals usually dealt with minor offences such as theft, boundary disputes, and minor quarrels. The duty of the gamsabhava was to resolve disputes in a non-hostile manner using common sense and compromise. They also had the authority to impose minor fines, but only in the presence of the village headman.

Ratasabhava

Delegates from each village of a particular district (Korale or Pattu) held office in ratasabhavas. The delegates were mohottalas (scribes), liyanaralas (clerks), badderalas (tax collectors) and undiralas (royal revenue collectors). They originally had jurisdiction on caste, marriage, and social status, and also the appellate jurisdiction of gamsabhavas.

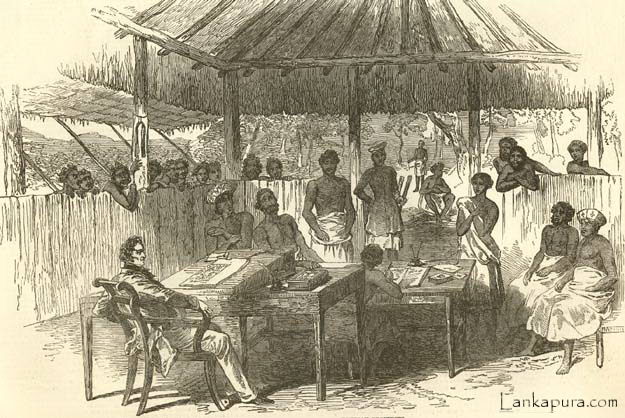

Interior of a Courthouse in The Kandyan Provinces. Image courtesy lankapura.com

Sakki Balanda

Just like the Inquirer into Sudden Death (ISD) or the Magisterial Inquiry we have now, the kingdom of Kandy, too, had a framework to investigate sudden deaths. It was composed of the prominent men of the district, and their duty was to find out the cause of death and mode of death. No one was allowed to touch a dead body until the process of sakki balanda was concluded. For example, the body of a person who had committed suicide by hanging was not supposed to be brought down until this process had been completed.

The State Officials

Kandy Chiefs in native dress 1882 at Dalada Maligawa. Image courtesy bl.uk

The scope of the jurisdiction of various officials depended on their status, and in the infliction of punishments, the officials had to take the caste and the rank of the wrongdoer into account.

1. Vidanes: Their duty was somewhat similar to the police officers of the present. They had the least judicial power over minor civil and criminal matters. A vidane could levy fines (ranging from 2 ½ pieces of silver upwards) and impose bodily punishment on persons of low caste.

2. Liyanarals, undiralas and koralas: They had more power than the vidanes and received complaints of trivial disputes. Their power was limited when it came to land issues or calling for punitive action, but they could impose fines.

3. Mohottalas and arachchis: This category of officials had extensive jurisdiction and could grant written decrees (wattoru) after adjudicating land disputes. They could deal with criminal offences, and could impose fines, ranging from 100 pieces of silver upwards.

4. Chiefs: Generally the lekams, ratemahatmayas and other chief royal officials of the King’s court and household had civil jurisdiction over all persons subject to their orders. It was only limited to some land cases.

5. Disawas and adigars (adikaram): They had extensive authority over all persons within their territory. They were next in line to the King and had jurisdiction over all civil and criminal cases, except ones regarding royal lands, and disputes between royal court members. But as they were persons appointed for nobility, disavas and adigars were not well aware of the law. Hence, they had to often consult their minor officers.

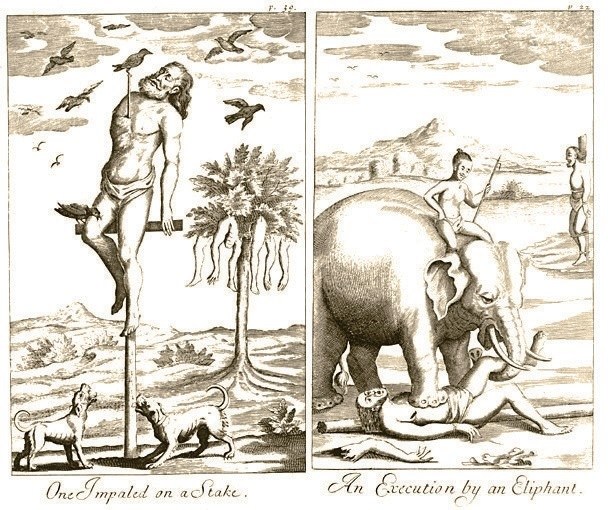

Graphical illustrations that appeared in the original book of Knox published in 1681, depicting appalling nature of capital punishment. Image courtesy torturemag.com

Maha Naduwa

This was a composition of higher officials and chiefs who worked in an advisory capacity and reported back to the king. The origin of this court can be traced back to the practice of the king referring to his chiefs on judicial matters, which he considered not worth his time and attention. Later, this tribunal acquired an original jurisdiction.

The King

The King was known as the fountain of justice. Image courtesy sundayobserver.lk

Known as the ‘fountain of justice’, The King had the ultimate authority over all matters. His extensive and exclusive power was on cases regarding suits between officials of his court, royal lands, suits between priests claiming rights to oblige principal temples, treason, rebellion, conspiracy against the royal family, and all homicides. A petitioner could individually approach the King, either directly or through a court official.

After The British Annexation

A group of British appointed Kandyan chiefs, with Hon. J. P. Lewis, Government Agent in 1905. Image courtesy karava.org

The Charter of Justice of 1801 established a new Supreme Court, headed by the Chief Justice and a Puisne Justice appointed by the King. It was vested with the supervision of criminal justice throughout the maritime provinces, a civil and equitable jurisdiction over the Town and Fort of Colombo, and over all Europeans and Eurasians of the maritime provinces. From the Kandyan Convention of 1815, the British guaranteed to all classes of people the continuance of laws, customs, and institutions which were in force among them already. But the ancient penal system was considered ‘uncivilised’ and was abolished, as it was thought to be contrary to the rules of natural justice, according to the English Law.

The enforcement of the Charter of Justice of 1833 established the British model of Judiciary in Sri Lanka, yet the long established gamsabhava was spared, and its procedure under the new system was left to the Supreme Court to be formulated. As gamsabhavas lost their efficacy, many land and agricultural disputes erupted. To find solutions to the problem of heavy delay in District Courts, the Government Agents and their assistants highlighted the importance of rejuvenating the traditional gamsabhavas. However, the judges did not support this view, and the judicial changes that followed created the Police Courts and the Courts of Requests of the British model in 1845.

The Ordinance No.5 of 1852 introduced the law of Maritime Provinces to the Kandyan Provinces; criminal law to all persons, and inheritance and succession of property only to Burghers and Europeans in Kandyan Provinces. Slavery was abolished in 1844 and the caste system gradually lost its validity in legal administration.

This authentic administration of justice is now antiquated to oeuvres and ‘Kandyan Law’ is the modified remnant of this ancient legal system that existed in the kingdom of Kandy.

Other Sources:

1. Cooray, L. J. M., An Introduction to the Legal System of Sri Lanka (first published in 1972, Stamford Lake Publication 2013)

2. A Brief Introduction To The History Of The Central Province

3. De Silva, M. U., Emergence of Two Legal Cultures in Sri Lanka and the Growth of a Litigious Nation under Western Powers

Featured image courtesy thuppahi.wordpress.com